OMA – Bigger than Koolhaas

OMA – Bigger than Koolhaas

Share

Office for Metropolitan Architecture, better known as OMA, is one of the most successful and acclaimed architectural practices in the world, with ground breaking projects in cities as far afield as Venice and Shanghai. That its first ever Australian commission should be Melbourne’s fourth consecutive MPavilion could be seen as a surprisingly modest venture for the practice. Not at all, says David Gianotten.

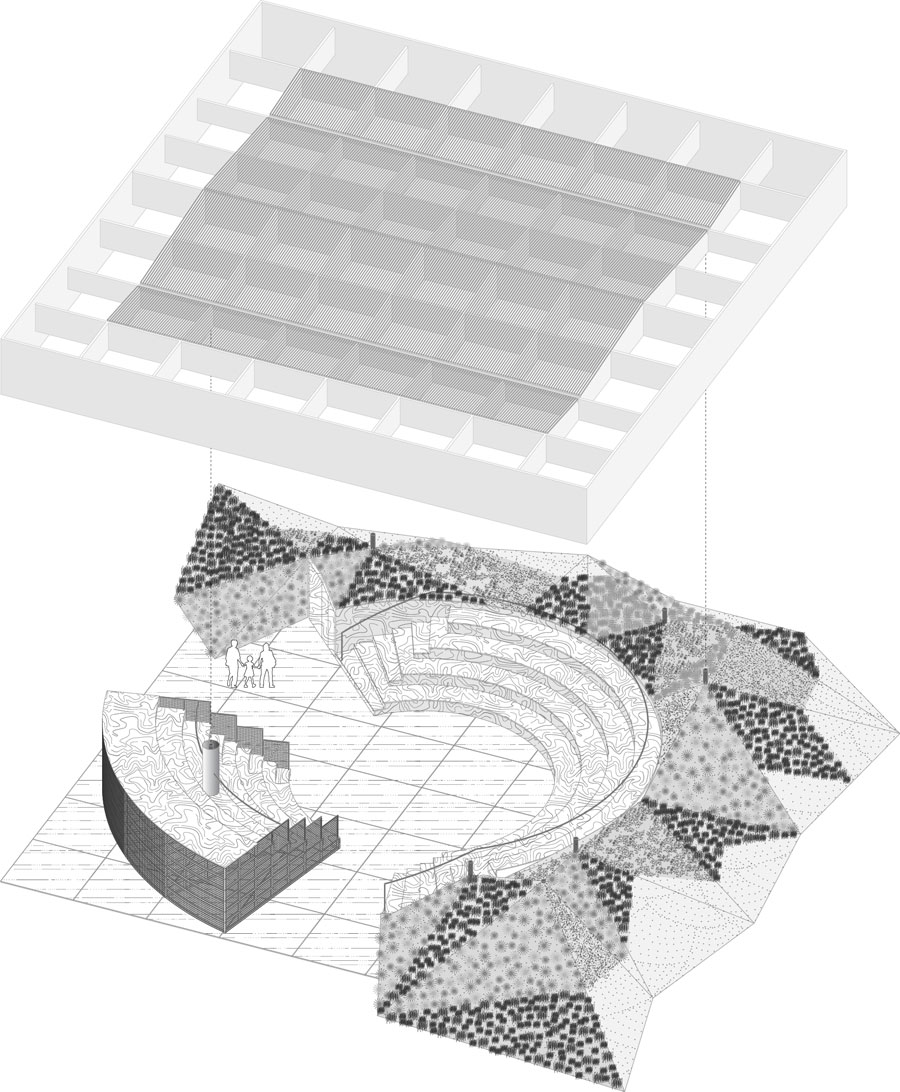

Following Sean Godsell in 2014, Amanda Levete (AL_A) in 2015 and Bijoy Jain (Studio Mumbai) in 2016, OMA has created the fourth in a series of temporary structures in Melbourne’s Queen Victoria Gardens. The MPavilion is an annual project, built to house a four-month program of talks, events, performances and installations. It’s become a firm favourite on the Melbourne design calendar – with another two iterations confirmed in July of this year – but, in the grand scheme of things, it could be considered a relatively minor project for a company renowned for its global reach and ambitious projects.

To believe this would be to misunderstand the OMA ethos, says managing partner-architect David Gianotten, who is also the co-creator of 2017’s MPavilion, along with Rem Koolhaas. “We never think about modesty, or about bigness or smallness,” he explains. “That for us is not a reason to take a project or not.” Rather, he and Naomi Milgrom, who commissions MPavilion through her eponymous foundation, have talked about the project for years. When she proposed OMA design this year’s structure it was her criteria that convinced. “She said, ‘I’m not asking you because of your practice, I’m asking you because of your ideas.’ And that, for us, was immediately, ‘OK – it’s a deal.’ She said, ‘We want you because of your thoughts and because of your process.’ Why would I say no?” says Gianotten.

Besides, the truth is that OMA didn’t always enjoy its current stature and size. Until the early 2000s there were fewer than 40 people in the company. Its rapid growth over the last decade (to more than 300 staff) has much to do with the extraordinary influence of Rem Koolhaas, Pritzker Prize-winner (2000) and a 2008 inclusion in Time magazine’s top 100 of The World’s Most Influential People. As the renowned architectural thinker and writer’s ideas and innovations have become more widely disseminated and applied, his practice’s reputation has followed suit. But it hasn’t been a linear affair. For a while, in the early part of the century, OMA was shareholder led, before shrinking and becoming completely independent again. Gianotten joined in 2008, launching the practice’s Hong Kong office the following year and becoming a partner in 2010.

It’s just in the last few years, however, that a successful business model has become firmly established. And this has been carefully structured to avoid succession issues or the concerns recently faced by a practice like Zaha Hadid’s, following her loss. “What you see is that the practice is not one person led anymore,” Gianotten notes. “The fact that we are called OMA, or Office for Metropolitan Architecture, already means it’s not fixed to Rem only… it’s a shell in which a lot of things can happen.”

That shell is owned by its nine partners, who also each have shares in the company. “All of us lead projects, because we’re all architects by nature. But besides that we all fulfil other roles.” For Gianotten, this includes lectures and PR tasks, plus plenty of travel. “Rem Koolhaas and I are the ones that work globally. All the others work regionally,” he says. “And the business model is actually quite simple. The nine of us come together every three months. We have strategic discussions for a week and then the outcome is transferred back to the company and implemented. So, we’re changing our agenda, let’s say, every six months and we measure its progress every three months, so it’s very direct.

I made very deliberate choices to want to have a broad spectrum. I wanted to build and I wanted to really understand how that worked.

“We have communication with all the levels in the company, so there’s no hierarchy between an intern versus a junior architect. Everybody sits on the table. Everybody’s exposed to design, everybody’s exposed to clients, everybody’s exposed to the management side of things… Of course, an intern takes a very small role versus me as the managing partner taking the overall role, but every role is significant and contributes.” It soon becomes apparent that, unlike many architects, Gianotten’s flair for business equals his design skills. This is innate, he says. As a youngster he played soccer, but soon became involved in organising contracts and management. This interest continued at Eindhoven University of Technology.

“During my studies in architecture I did several courses related to the business side. For me, that has been different from day one. I made very deliberate choices to want to have a broad spectrum. I wanted to build and I wanted to really understand how that worked. After architecture school, even during it, I could build my first own project. I’ve always been producing, and at the same time I wanted to understand and refine the business model behind architecture, and that’s what I’m constantly still doing. “So for me, I don’t see it really as a divide, I see it as a natural extension, and I simply also like to do it.”

We’re changing our agenda, let’s say, every six months and we measure its progress every three months, so it’s very direct.

He also believes business and creativity are less disparate than some may suspect. “I wouldn’t say that there is common language, but what they both have in common is that they have to be flexible to accommodate things they cannot predict. And that’s a skill in itself. When you take the best of both ingredients, design with management can be fun, and management through design can be fun.”

But he’s quick to stress that not everybody feels this way. And that, if business skills don’t come naturally, those people should stick to what they’re good at. “That’s a mindset, that’s an attitude. And it’s not something you can learn, I think. It’s also not something you can choose – you have it or you don’t.” He says he talks to people without design experience who have been appointed to manage practices at a partner or shareholder level. “They don’t survive most of the time because they don’t understand the flexibility that design needs,” he says. “You need to have this certain elastic situation where you can push and grow, and where you can also engage people that are in it, make people responsible.”

Currently, he says he spends about 40 percent of his time on the business side of his role and 60 percent on design, before reconsidering… “If I think really critically about it, I can’t even divide it. Maybe I’m working 100 percent on both.

“We’re constantly innovating our business model,” he adds. “With that agenda that we have, we look for our clients, and we look for where to best operate, and where we can innovate, where we can play a role for society, or where we can play a role for the city, or play a role with a building. That is very conscious; it’s not an opportunity driven process within our company. I also really want to keep it like that, because if you’re completely dependent on what is coming at you and the influence that is coming at you, you also become led by opportunities. You have to answer to them. We can select from opportunities, and then we also determine what our agenda should be.”

This article originally appeared in AR152 – available online and digitally through Zinio.

–

Watch the video fly-through of the OMA-designed MPavilion.

You Might also Like