OMA’s The Interlace

OMA’s The Interlace

Share

Location: Singapore

Architect: Büro Ole Scheeren

Review: Erik L’Heureux

Photography: Iwan Baan

The Interlace, completed in 2013, is a large, gated condominium located alongside two lush jungle settings in Singapore – Telok Blangah Hill Park and HortPark. It is flanked by an expressway and Hewlett-Packard’s headquarters; a short drive west from Singapore’s central business district.

It was designed by Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) and later claimed as a product of Ole Scheeren’s independent talents as he sought to establish his own practice, Büro Ole Scheeren, out from the long shadow of the OMA empire.

The Interlace sits at that unwieldy scale, too large to be judged as a piece of singular architecture, and yet not quite sizeable to constitute an area claimed as urban design. Yes, it is big, the size of a small village, easily housing over 3000 people when fully inhabited.

CapitaLand, the state-owned developer, claims that it is one of the largest and most ambitious residential developments in Singapore. With 1040 residential units and 1132 car-parking keys, the development sits on over eight hectares with a plot ratio of 2:1, the total gross floor area (GFA) tops out at 170,000sqm.

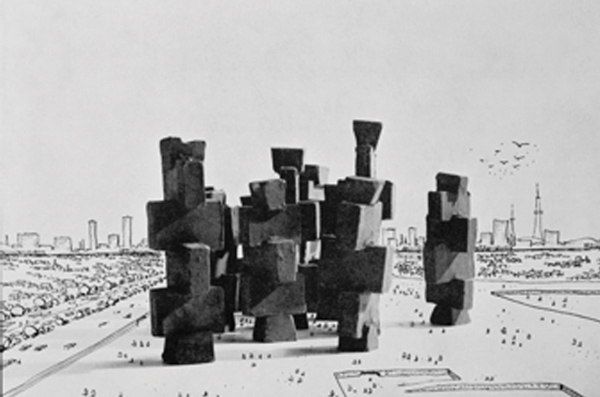

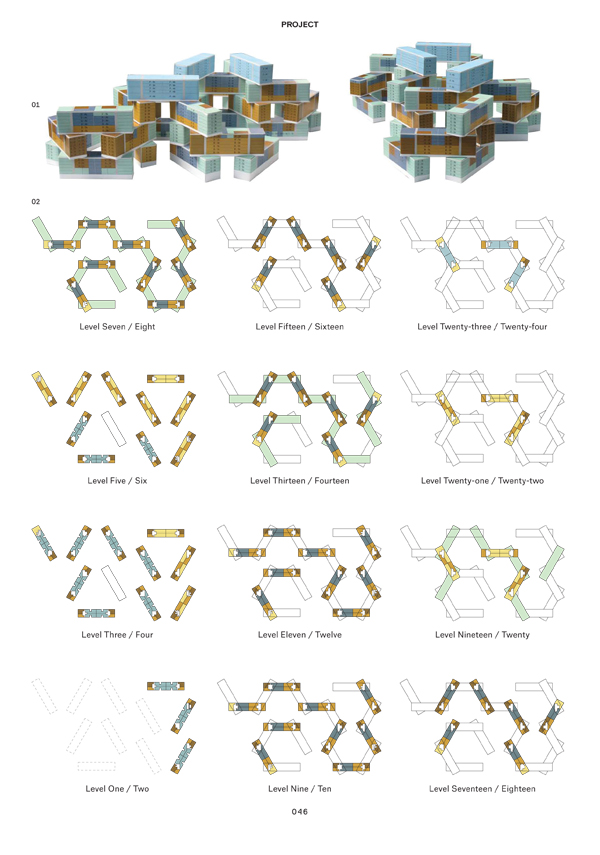

The design is configured as a series of 31 six-storey blocks stacked in a hexagonal pattern that crisscross the site, recalling the metabolism experiments of Arata Isozaki’s 1960 Joint Core System for Tokyo or the Shinjuku Terminal Redevelopment project of the same year by Masato Otaka and Fumihiko Maki.

OMA director, Rem Koolhaas’ interest in Japanese Metabolism is well known, illustrated in the publication Project Japan: Metabolism Talks… (2011). The start of the design process for the Interlace occurred in the same year as this publication and the influence is clear. I imagine the pages snuck onto Ole Scheeren’s desk during concept design; then again OMA’s modus operandi has long been to sample from Modernism and the historical avant-garde to produce its architectural language. The Interlace is no different.

The project’s design is a diagram of regulation, where prescriptive building codes and demands for extreme sellable efficiencies, due to land costs far exceeding construction cost, drive the architectural moves. In Singapore, maximising GFA is architectural bedrock, where the tools and tricks of the trade can make or break a project (and an architect).

As a diagram of GFA efficiencies and code acquiescence, the Interlace is full of creative intelligence; the six-storey block heights can be read as a product of a GFA loophole, where the terraces placed six storeys below (and covered) are not counted in the total GFA sum – five storeys and the loophole does not apply, seven storeys and one is wasting real estate. Likewise, the block length is determined by sticking back-to-back two clusters of four residential units to a single core, maximising one-way travel distance. This slight of hand eliminates the need for two means of egress stairs at each lift lobby, greatly amplifying the floor plate efficiency.

Indeed, the majority of the blocks are configured this way. Window balconies, open terraces, planter boxes and perforated slabs are the visible syntax of GFA regulation, forming the basis for the architectural articulation.

Between the stacked blocks, eight large courtyards are formed with the typical condominium trappings: the 50m lap pool – a ‘fun’ pool as all pools supposedly are – tennis courts, fitness centre, gymnasium, garden zone, spa areas, children’s playgrounds, walking track and barbeque areas. Tropical tropes are concentrated about the ground plane: lush planting, green walls and sounds of percolating water. Yet at the upper levels, the architecture fails to reflect the hot and wet climatic realities of being on the equator. For example, the block envelopes could have been veiled in stunning brise soleils or ventilation screens, rather than the temperate-centric black tinted glazing and textured white paint.

Balcony plantings are far and few between and rooftop gardens are paltry compared to the verdant jungle growing beside the development. Scheeren claims that landscaping will grow in at these locations, but one’s tropical sensibility suspects that the size of the upper-level plantings is just too small to make a significant impact. And the immense artificial stone cliff, similar to the system applied at the nearby Universal Studios, is an entirely unfortunate solution to the challenges of steep topography and significant rainwater runoff.

The most effective trick that OMA/Büro Ole Scheeren implements in the design is flipping the configuration from a normative vertical one found throughout much of rapidly densifying Singapore, as seen in Zaha Hadid’s tower configuration a few miles from the Interlace (also developed by CapitaLand).

A horizontal orientation is prioritised rather than the vertical one, creating a single, large interconnected super-scale mega structure. Large gaps between the zig-zag stacked blocks allow not only for a robust distance between the units but also to views of the tropical jungle beyond. These are impressive moments in the architecture, recalling the etchings of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, where labyrinthian space, bold and dramatic, reflects the ambitions of growing Singapore. Piranesi, it must be noted, was describing imaginary prisons in his Le Carceri d’Invenzione, while at the Interlace an expanding middle class comprised of ‘well-heeled locals and expats’ with discerning taste enjoy a composed tropical lifestyle, where ‘community’, ‘space’ and ‘nature’ are the celebrated trappings of having ‘made it’. In an ironic twist of fate, the ambitious Metabolist design is de-radicalised and made into another real estate proposition of programmatic singularity. The inhabitants of the Interlace reside in a gated and well-protected condominium, with perimeter fencing, security patrols and night-time illumination, or, as Koolhaas might claim of its occupants, ‘voluntary prisoners’.

The design is a diagrammatical intense and novel configuration, but not a powerfully and ambitiously urban one. It is here at the urban scale that the project falls entirely short.

Koolhaas (and by default Scheeren) have championed programmatic diversity and programmatic compression as the engine of an architectural resurgence since the 1970s. From Delirious New York (1978), the New York Downtown Athletic Club, the Parc de la Villette competition entry, to the programmatic diagrams of the Seattle Public Library, diversity of programs squeezed together in close proximity set the stage for a reinvigorated architectural and urban project – the self-proclaimed ‘culture of congestion’. Yet, at the large scale of the Interlace, eight meagre commercial spaces, about 75sqm each, remain unoccupied at the date of writing, are intended to complement a neighbourhood of 3000 people.

For comparison, Koolhaas’ favourite muse, New York City, in eight Upper East Side residential blocks at 72nd Street, 5th Avenue and Central Park – with the same area of the Interlace – illustrate a deeply urban configuration. Replete with shopping, schools, supermarkets, doctor offices, art galleries and more, fuelled by a bounty of residential units that far exceed the quantity of the Interlace.

In Brooklyn, for a softer comparison, in the sleepy Carroll Gardens neighbourhood, there are about 1000 units in townhouses four- to five-storeys in height spread out over eight blocks. Two churches, a variety of restaurants, retail shops, green areas, streets and backyards produce a residential neighbourhood full of vitality, life and identity. There are only a few small backyard pools, but here life, as celebrated by Jane Jacobs, occurs on the public street and not in the private compound.

The blame for the lack of urban programmatic intensity could be aimed at the developer or on regulations in Singapore, or even on the market that seems to seek only condominium trappings. But of all practices operating today, OMA has the intellectual legacy to push for a more robust metropolitan experience, full of functional variety, energy and neighbourhood publicness.

Indeed, this has long been OMA’s calling card. The Interlace however neither allows for programmatic assortment or the public intensity of a functioning urban environment. Architectural projects at this scale should be public not gated, programmatically diverse not singular and, ideally, driven by multiple architects and multiple developers.

Yes, OMA/Büro Ole Scheeren’s design is an intelligent and powerful diagram of regulation and large-scale financial capital (one might even say a voluntary prisoner of architectural regulation itself however novel it may appear), but architecture and urban design must be judged by a higher standard, a standard that celebrates and establishes a desire to want to live in a spatially and programmatically diverse tropical city – a tropical metropolis – not just swim in another gated condominium fun pool.

Project Details:

LOCATION: Alexandra Road/Depot Road, Singapore

COMPLETION DATE: T.O.P. (Temporary Occupation Permit) Sep 2013

GROSS SQUARE FOOTAGE: 1,829,864sqft (170,000sqm)

CLIENT: CapitaLand Residential Singapore Pte Ltd

DEVELOPER: Ankerite Pte Ltd (joint development between CapitaLand Residential and Hotel Properties Limited)

DESIGN TEAM: Ole Scheeren, partner-in-charge, lead designer; Eric Chang, associate

PROJECT ARCHITECTS: Toby Wong, Andrew Lo, Erik Amir

PROJECT TEAM: Heidi Blais, David Brown, Andrew Bryant, Catarina Canas, Ben Chan, Sean Hoo Ch’ng, Wynn Chandra, Steven Y.N. Chen, Dan Cheong, Ryan Choe, Ying Chee Chui, Benjamin Claeys, Renato Juarez Corso, Sascha Daum, Jasmin Delic, Charles Gosrisirikul, Nozomi Kanemitsu, Winnie Lam, Samuel Liew, Rita Liu, Cora Lutz, Ryan Maliszewski, Luis Aguirre Manso, Sandra Mayritsch, Karine Mellet, Michelle Miller, Eugene Oh, Gabriele Pitacco, Yijun Qian, Mimi Shen, Joseph Tang, Uri Verthime, Shuo Wang, Esther Yang, Ali Yildirim, Jing Zhang

CONCEPT TEAM: Jens Eberhardt, Paloma Hernais, Benny Ho, Jaime Oliver, Hiromasa Shirai, Benjamin Ahrens, Johannes Oesterle, Shelley Zhang

EXECUTIVE ARCHITECT: RSP Architects, Planners and Engineers Pte. Ltd., Singapore

ENGINEERS (STRUCTURAL, CIVIL, MECHANICAL, ETC.): Arup, Beijing (Concept / SD structural engineering); RSP Architects, Planners and Engineers Pte. Ltd. (structural engineering); and Squire Mech Pte Ltd, Singapore (mechanical engineering); T.Y.Lin International Group Ltd., Singapore (civil and structural engineering, construction engineering and inspection)

LANDSCAPE CONSULTANTS: OMA Beijing (Concept / SD) / ICN Design International Pte. Ltd., Singapore

SUSTAINABILITY CONSULTANTS: Arup, Hong Kong (Concept / SD)

GRAPHIC DESIGN (LOGO): 2×4, New York

QUANTITY SURVEYOR: Davis Langdon & Seah Singapore Pte Ltd

LIGHTING CONSULTANTS: Lighting Planners Associates (S) Pte Ltd, Singapore

ACOUSTICAL CONSULTANTS: Acviron Acoustics Consultants Pte Ltd, Singapore

GENERAL CONTRACTOR: Woh Hup Pte Ltd, Singapore.

You Might also Like