The debate: Life after death

The debate: Life after death

Share

Can an architectural practice survive the demise of a ‘starchitect’? Recent events have prompted Edwin Heathcote and Simon Nelson to tackle this timely topic.

THE CASE FOR: Simon Nelson, practice principal, SEED (Studio for the Exploration of Evolutionary Design)

History and conventional wisdom tells us that the death of a starchitect will lead to the demise of their practice. But times are changing, practices are becoming bigger and more professionally run, and the recent the untimely death of Zaha Hadid has ignited a renewed interest in this subject. The issues that arise not only have ramifications for ‘starchitect’ practices, but also for any practice where key partners are seen as its lifeblood. But really, the question shouldn’t be ‘can a practice survive’, because, simply, they can. Instead, the focus needs to be on how they can survive. As with so much in business, left to chance, the odds are against survival, but with proper planning, a practice can survive and thrive even after the demise, or maybe even retirement, of the person who gave the practice its name. So what needs to be done in order to protect the long-term future of a practice to ensure it survives its founder? The answers are wrapped up in those terms so many architects hate – strategy, marketing, planning, culture – in other words, in employing sound business management practices.

“By building a brand, practice culture and developing a team of senior practice leaders, it is possible to thrive under a new generation of owners.” – Simon Nelson

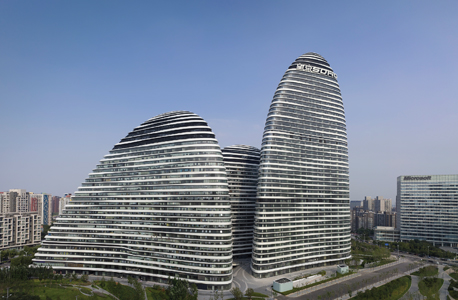

We need to recognise that a starchitect is a brand and that brands need to be managed to ensure they endure. This is easier where the practice has a distinct style, such as in the case of Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA), known for forms created by parametrics, where [Hadid’s successor] Patrik Schumacher says clients expect a certain typology. Since the passing of Hadid in March 2016, the practice has won significant new projects and looks secure for a number of years to come. The challenge will come as parametric design and ZHA’s style evolves, but that is a challenge the practice would have faced with or without Hadid. ZHA’s chances of survival are also helped by its management structure. Schumacher was already a partner with a high level of visibility, and he is supported by a group of directors that has a combination of those with extended service who understand the practice and those with wider industry experience, not least Mouzhan Majidi, the appointment of whom is now looking rather inspired, as ZHA leverages his experience as CEO of Foster and Partners.

ZHA has become synonymous with parametric design.

Another practice that manages its brand well is BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group). Not only does it manage its brand, but there is also a great, if not greater, emphasis on managing the business, building a culture and codifying the design process, with Ingels stating that this was a significant focus while establishing the New York office. With a capable team of partners and a very focused CEO in Sheela Maini Søgaard, much of what is needed to survive Ingels is already in place.

Others have taken a different approach to the issue of succession planning. Richard Rogers and his original partners have planned their exit for many years, managing the transition to the next generation of partners. To facilitate this, there has been a name change, to Rogers Stirk Harbour and Partners, reflecting the new creative and managerial forces, while a further name change is anticipated, with the dropping of the name Rogers at an agreed interval after his passing. Through long-term and careful planning, the practice has positioned itself for the inevitable changing of the guard.

Madrid Barajas Airport, terminal 4 by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.

In conclusion, not only can practices survive the demise of their starchitect, but valuable lessons can be learned through the study of how they do so. All practitioners need to consider some form of succession planning and, through building a brand and practice culture, and developing a team of senior leaders, a practice can thrive under a new generation of owners.

THE CASE AGAINST: Edwin Heathcote, writer, architect, architecture critic of The Financial Times, editor readingdesign.org

This is the easier side of the argument to argue. Mostly, because it’s never been done. No major architectural practice established under the name of its founder has survived much beyond their death. It might be a little surprising, after all, we know that architecture is collaborative and a work is never the product of a single mind… and yet.

The question has been brought up again by the death of Zaha Hadid, whose distinctive and fiercely original work put her among the select few starchitects who bestride the world like cultural colossi. But of the cohort, which includes Rem Koolhaas, Frank Gehry, Renzo Piano, Jean Nouvel, Tadao Ando, Herzog & De Meuron, Foster and Rogers, Hadid was the first to go, so there is no real precedent. Instead, we have to go back to see how the practices of Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Kahn and the other greats of modernism continued after their demise. The answer, of course, is that they didn’t.

Louis Kahn looking at the ceiling of the Yale University Art Gallery. Image by Lionel Freedman.

Great architecture, like great art, is at least in part predicated on the ‘aura’, the halo of authenticity and genius that surrounds the real thing. Clients and cities want a piece of the stardust that glitters in the wake of the first-class arrivals of the big names. They want to be associated with the star, an association that brings cachet and prestige to both client and project. Partly, this is to do with the charisma of the individual architect, a cocktail of charm and an ability to impart a sense of creativity. The client feels valued. Starchitecture is not a million miles from starf****ing. When the charismatic leader of the cult is gone, the glitter fades. You get the gist of the style, the afterglow perhaps, the skidmarks.

“Clients and cities want a piece of the stardust that glitters in the wake of the first-class arrivals of the big names.” – Edwin Heathcote

The curious thing is that this does seem to be a particular problem for architecture. The great fashion houses have mostly survived the deaths of their founders, the auto-manufacturers similarly carried on without their Fords or Ferraris around. A few major practices have attempted to address their future through succession – most obviously Richard Rogers, who changed his practice’s name to include his amanuenses so that it now reads – Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners. Koolhaas meanwhile has always been keen to credit his colleagues and practices not under his own name, but under the typically generic Office for Metropolitan Architecture (of which Hadid herself was once a partner). The others, Gehry, Piano, Nouvel, [Álvaro] Siza and so on seem to have no plan – just as Oscar Niemeyer had no plan when he died. Legacy, on the other hand, seems to be something else. The big names are thinking about how they’ll be remembered – even if they may not be thinking too hard about how their colleagues will continue. Norman Foster has allegedly built a bunker in a Swiss mountain for his archives, Herzog & De Meuron have built an impressive building on the edge of Basel for theirs. Zaha Hadid bought the prominent Bauhaus-style building by the Thames that was formerly the home of the Design Museum in London to house her archive.

Norman Foster with a model of the Reichstag. Image by Nigel Young.

The only escape from oblivion for architects hoping to leave their practices running after they’re gone is in association. SOM has survived just fine without Skidmore, Owings or Merrill, and Kohn and Pedersen have survived the death of Fox. Perhaps though, this is a very good thing. Do we want architecture to be about brands? Do we want the design of buildings and cities to be analogous to that of the superficiality and commerciality of the world of haute couture? Architecture is about interpretation and intelligence, about the application of a particular way of thinking onto the landscape and into a very specific cultural context. It is true that Patrik Schumacher’s thinking and his ideas about Parametrics have long been one of the underlying forces behind ZHA, but will one of his buildings be a Zaha building – or even a ZHA building? Or will it be a Patrik Schumacher building? Despite what the letterhead and the logo on the drawing say, we already know the answer.

This article originally appeared in AR149 – available online and digitally through Zinio.

–

Want to learn about a new approach to fee proposals? Ian Motley writes for AR over here.

You Might also Like