We shouldn’t be “designing just for design’s sake,” says Edition Office

We shouldn’t be “designing just for design’s sake,” says Edition Office

Share

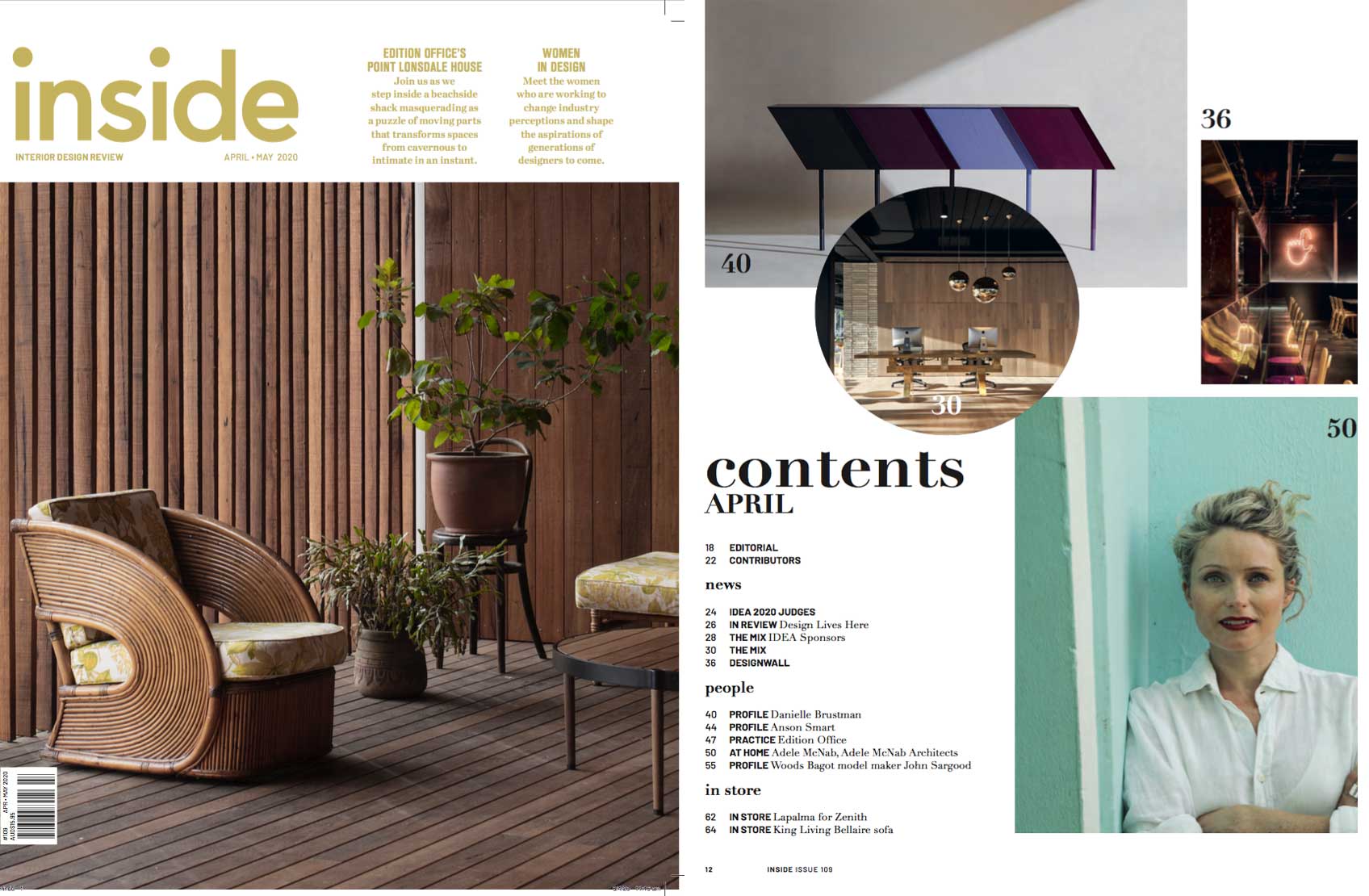

Within the grey walls of their Fitzroy studio, Edition Office directors Kim Bridgland and Aaron Roberts craft buildings that move beyond beauty to become considered explorations of our relationship to place and context.

There is something mesmeric about an afternoon spent listening to Edition Office talk about design philosophy. In a sweltering Fitzroy studio with the windows thrown open onto the street below, Aaron Roberts and Kim Bridgland make Australian design sound aspirational or, at the very least, their sort of design.

The duo is behind the National Gallery of Victoria’s latest Architecture Commission, which put them, together with contemporary artist and Kokatha and Nukunu woman Yhonnie Scarce, on the map. With just four years and a handful of residential projects to their name, the pair also scooped up Dezeen’s latest Emerging Architect prize.

While Edition Office is in its infancy, Roberts and Bridgland are design veterans. Roberts briefly ran his own practice in Japan, while Bridgland clung to architecture as an escape from a chronic childhood illness. They met while undertaking a Masters of Architecture at RMIT.

“We were both mature-age students, so when you panned around the room at orientation for people you might be able to connect with, we gravitated to each other,” says Roberts.

“Afterwards we went and got coffee, curious about each other’s backgrounds and the paths we’d taken to get where we were.”

They worked together at Room 11 Architects before a shared interest in the complex narrative that drives design propelled them to strike out on their own.

The name Edition Office alludes to Roberts and Bridgland’s commitment to make everything they do – be it project, lecture or body of work – part of a continuous narrative, an addition to an archive that is ongoing and can sit comfortably within a larger editorial context.

“We had the opportunity to reframe the discussion, reframe what we were doing from a design point of view. Room 11 didn’t really support that or the way we wanted to practise together,” says Roberts.

“You don’t often get someone who will call out your bulls**t. You have to try and see that yourself and sometimes you’re blind to it. But I think one of our best skills is being able to rapidly edit an idea,” adds Bridgland.

For Edition Office, that editing process sees every design element pared back to what its need will be. The conceptual framework around the design is reviewed and adjusted, condensed and distilled and ultimately refined. It’s not a rushed process. Both appreciate the opportunity to pause and reflect on their design and practice, lamenting the tendency within the industry to constantly rush onto the next stage.

“Something that was incredibly important to us when we began a project, or this very practice, was not to work towards design for its own sake. We’re interested in working on design that is inherently being placed within a context, socio, historical or ecological,” says Bridgland.

“Designing for its own sake is more stuff. More stuff with which we surround ourselves that is meaningless or challenging and troubling, especially considering the climate position we’re in. Not designing architecture as a facilitator for the lives we live, as something that is beneficial and connects us back to each other and back to the place we’re living is dangerous.”

Life is messy and clients are capricious, and Edition Office is ultimately a practice that designs houses. Loftiness doesn’t always align with the owner’s vision, but the practice doesn’t push its narrative on anyone.

“We’re interested in Glenn Murcutt’s ‘touching the earth lightly’ type of narrative. In designing houses, formally, that have connectively to their place, in terms of orienting to their climate and making sure they’re passively designed. But we’re not trying to declare what that narrative is. We’re simply making the client aware there is a question of relationship to place. It’s loose. It’s enigmatic. We’re not meant to suffocate them in the politics of something they’re not buying into, they don’t want to carry the burden of,” says Bridgland.

“We’re very interested in working with formal languages that are culturally ambiguous and can lead to different responses. So [it means] not working with things that have a very clear lineage in a European context from an architectural heritage perspective. Not having buildings that are feathery with very loose edges, kind of aggregate models. I think you’ll probably find that all the buildings we do have a bound-ness to them. They have an edge and a defined sensibility.”

In many of Edition Office’s designs that ‘bound-ness’ is explored in pavilions. In Hawthorn house, the project that earned the practice the Dezeen nod, pavilions create a concrete shroud that rearticulates old design tropes and reinterprets spatial conditions. Point Lonsdale has four interlinked pavilions that transform one open space into a series of intimate areas.

“It’s less about the pavilion as a type and more about breaking up parts of form and volume to allow more to go into the space. So pulling it apart means you can have a garden in it or you can have light, you can have a view to the sky or you can have a private space within the framework of the architecture. Whereas the solid block that’s not broken down tends to have less possibility in relation to that,” says Roberts.

This sense of architecture as a framework around personal context is more overt in the work Edition Office does other than its houses. Both Bridgland and Roberts recognise they are in a position of privilege as white male practice leaders, but their architecture seeks to give a voice to anyone but.

“Everything we do hopefully comes from a higher level of life, an empathetic and sympathetic position,” says Bridgland.

“Our heritage belongs to the dispossession of Indigenous communities and it’s up to every one of us to make sure we’re inclusively telling a whole and accurate history.”

“It’s a difficult conversation for architects, developers and designers to have,” adds Roberts.

“That idea of site ownership and the fact that we’re all economically connected and beholden to that system is not pretty. We’ve spoken about the urban realm being a continuation of the colonial project and there are a lot of questions about what it means to continue that project.”

In working with Kudjla and Gangalu artist Daniel Boyd on the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander War Memorial in Canberra and Scarce on the NGV Architecture Commission, Edition Office gives a voice to the historically voiceless, deliberately creating something that you can’t turn away from. The NGV Commission in particular stands in direct dialogue with the Roy Grounds-designed building – an exemplar of the European enlightenment tradition.

“The NGV pavilion stands up and says, ‘I’m also legitimate. I’m also equal’. There’s this dialogue between the two heritages. Our building came from a conversation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous collaborators around mixed heritage, around our identity. It acts as a conceptual trigger of an equal conversation from one part of our community to the other, which is often discordant,” says Bridgland.

“It’s the perfect example of what we want to do – to see architecture as having a role to play in the cultural dialogue around what it means to live, design and work in Australia. And to a certain degree, everything that we make in a dual environment should have dialogue back to that,” concludes Roberts.

Photography: Peter Tarasiuk and Ben Hosking.

This feature originally appeared in inside magazine – on newsstands now!

You Might also Like