“Indigenous architecture is not a style, but a culturally appropriate process” – Alison Page

“Indigenous architecture is not a style, but a culturally appropriate process” – Alison Page

Share

All architecture in Australia should be an act of co-creation with Indigenous Australians and Indigenous design principles, says interior designer and Walbanga and Wadi Wadi woman Alison Page.

In her new book, Design: Building on Country, cowritten with Paul Memmott, Page outlines how all buildings, no matter their use, should be an extension of Country.

“We aren’t second hand Americans,” Page tells ADR. “We are home to the oldest living culture in the world, so we’re actually older than America and England.

“We should be showing them how to have a deep and mature identity despite having chapters in our history that are extremely painful, and using our architecture and the design of our cities as part of that healing process.”

A new Australian design

It was while studying interior design at university in the 1990s that Page discovered Robin Boyd’s Australian Ugliness and our “obsession with pasting imported woods over native boards.”

She says this tendency to import architecture and design from overseas predates Boyd’s seminal text.

“The colonisers took buildings they liked in England and replicated them here,” she says.

“You can see that along Macarthur Street in Sydney as well as in every major city. Imported architecture that is just planted on top of place instead of allowing Country to inform it.”

Page says new Australian design should be doing the opposite. It should be drawing from our millennia of history pre-colonisation.

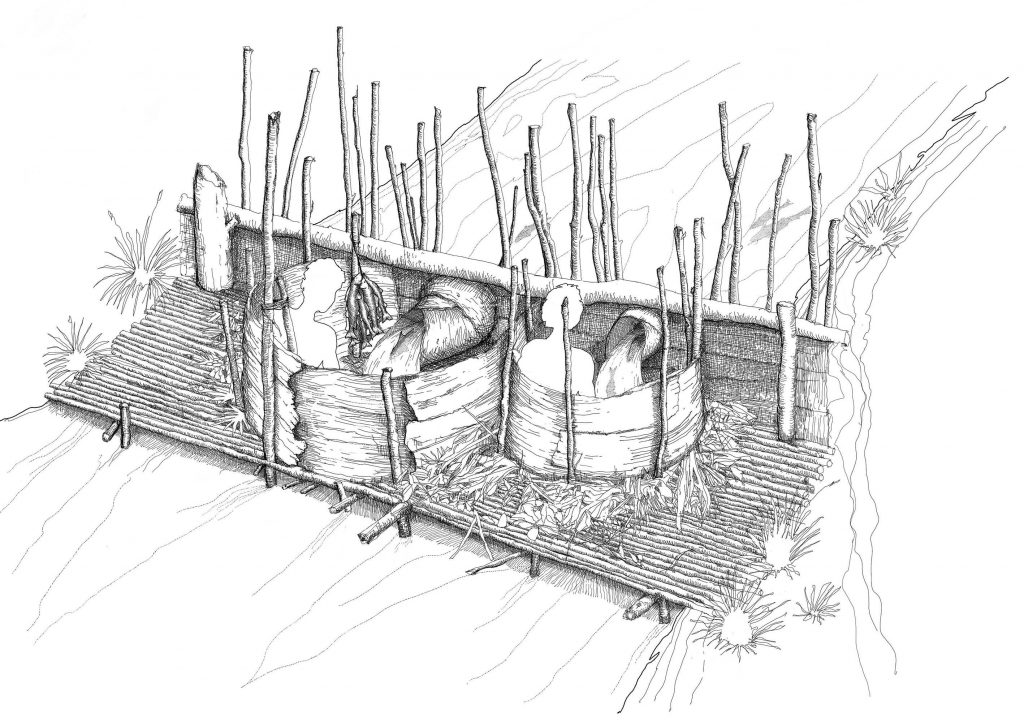

“Our culture’s systems, technologies and social structures were designed with care for the land, sea and sky and the people in them as a guiding principle,” she says.

“It was a holistic ecological order than ensured the survival of untold generations through major climatic changes and an everyday life that was filled with art, ceremony and storytelling.

“Isn’t this something we as Australians can all embrace as our identity?”

To truly create our own identity in the built environment, Page says architects should be engaging with Indigenous Australians in the same way they engage sustainability experts now.

“When the green movement came in, architects were suddenly required to look at sustainability within their development. In the same way, connecting with Country should be mandated in all future designs.”

Learn from “thousands of years of ingenuity”

For Page, the benefits of engaging with Indigenous Australians goes beyond aesthetics. It’s also about drawing from the rich world of traditional knowledge.

“There’s a lot more to Aboriginal culture than meets the eyes,” she says.

“Beyond the dots and the painting and the dances that you see, there is this world of traditional knowledge that is very sophisticated and very scientific.

“This knowledge helped Aboriginal people survive on this continent for 65,000 years. So if we want to survive for another 65,000 years, we should be treasuring it and appreciating it.”

Page cites the boomerang as an example of Indigenous ingenuity drawing its form and function from nature and the landscape.

“Was it by observing bird wings or watching leaves fall from a tree?,” she says.

“We don’t know, but either way, it comes from the connection with Country and with this cleverness that we shouldn’t ignore.”

Move beyond the totemic

The first step for architects to engage with Indigenous communities and Indigenous design principles is to go beyond the surface says Page.

She alludes to the “simplistic way of interpreting Aboriginal culture” of the 1990s, in which architects shaped buildings as literal interpretations of a community’s totem.

“Totems are important, but architects should be spending time with the community to understand what it is about that totem and why they have a connection to it,” she says.

“For example, the Dharawal people of NSW have a lyrebird as their totem because they were well-known speakers of many languages and the lyrebird mimics the sounds of other birds.

“So in interpreting the lyrebird, it’s much more relevant to embed many languages into the design as opposed to representing the animal itself.”

This deeper understanding extends to buildings that aren’t specifically designed for Indigenous communities.

It can be as easy as designing an office block with a garden inside, suggests Page, then providing workers with the opportunity to water the trees every day as an act of ceremony that engages with Country and nature.

“Ask yourself, ‘What happened on this site. Who was occupying the space before? What was growing there? Were people camping there? Were people going there to collect food? Was it a sacred site?’

“Incorporate all that into your design.”

Merrima Aboriginal Design Unit at which Page worked. Photo: Brett Boardman

“Actually work with Aboriginal architects”

In Building on Country, Page quotes Indigenous Canadian architect Douglas Cardinal: “It is time that colonial nations acknowledge that it is no longer acceptable for design to be done without us or for us, but by us.”

In speaking to ADR, she talks about how “architecture coming together with Aboriginality” had never occurred to her as a young designer.

She says many Indigenous Australian children would still view the profession as “some island off the coast, miles and miles away from their reality.”

But she believes the only way for new Australian design to be an extension of Country is for those children to be involved.

“Think of a building as an artefact. In our belief system, it’s a living entity, a member of our family, a functional tool for living or working in,” she says.

“It becomes this vitalised energised artefact that we engage with every day, which is a hell of a lot more meaningful than how we view architecture now.

“If you want that – if you want to have that level of cultural energy – your architectural team should be led by Indigenous practitioners and storytellers.”

Architects should also be engaging with Indigenous people in the design and construction process, something Page supports with the National Aboriginal Design Agency, which brokers partnerships between Aboriginal artists and architects to design custom architectural hardware or integrated design in buildings.

“In a practical sense, social justice in design means maximising opportunities for the project to be a vehicle for the economical independence of Indigenous people,” she writes in Building on Country.

“It gives Indigenous people a voice in their environment, continuing the culture they have practised for millennia and ultimately helping all Australians to understand more about the places they engage with.”

Now more than ever

Jefa Greenaway and Tristan Wong transformed the Australian pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale into an exhibition that is inclusive of our First Nations people and our neighbours.

Titled In|between, it showcased a selection of realised and non-realised projects that “powerfully represent Indigenous and non-Indigenous identity simultaneously”.

For Page, this installation is proof that Australia is ready to understand its “true history” as a nation, to learn more about what really happened in this country and engage with it.

“Now is the time for these stories to be heard,” she concludes.

“The country and the world is crying out for the stories of Indigenous people. So I think, in the next 10 to 15 years, we’re going to see an architecture that is much more informed by family, community and our connection to nature, but also by truth telling.”

Design: Building on Country is being published by Thames&Hudson in conjunction with the National Museum of Australia and supported by the Australia Council for the Arts. It’s available online and in all good book stores.

Lead photo: Alison Page by Joseph Mayers.

You Might also Like