The Australian Pavilion moved beyond the “clichés and stereotypes” – Jefa Greenaway and Tristan Wong

The Australian Pavilion moved beyond the “clichés and stereotypes” – Jefa Greenaway and Tristan Wong

Share

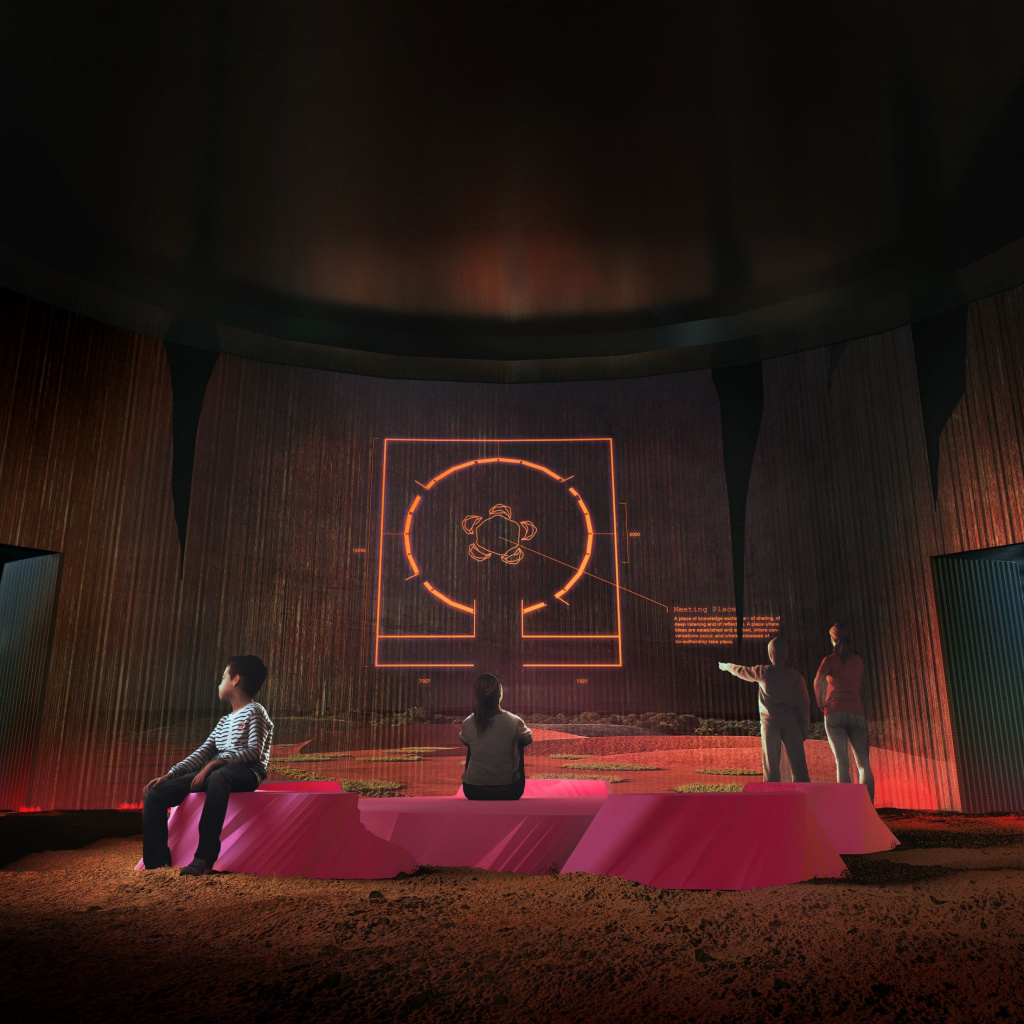

The proposed Australian Pavilion at this year’s now postponed Venice Architecture Biennale was carefully orchestrated to be inclusive of our First Nations people and our neighbours.

We caught up with Jefa Greenaway and Tristan Wong to talk about why that’s all the more important, regardless of the postponement, and how architects and designers can start applying learnings from the project right now.

Like many of us, SJB director Tristan Wong and Jefa Greenaway of Greenaway Architects had high hopes for 2020.

The year may have started with Australia racked by devastating bushfires, but the promise of creative healing lay ahead.

Selected by the Australian Institute of Architects to head up our pavilion at the 2020 Venice Architecture Biennale, their inspired response to Biennale curator Hashim Sarkis’ overarching theme ‘How will we live together?’ celebrated contemporary Indigenous culture and also invited in our Pacific neighbours under the banner In|between.

And then the global COVID crisis hit. With the Biennale postponed to May 2021, Greenaway and Wong hope to pick up the pieces later.

Greenaway says, via a Zoom conference in which Wong inhabits another digital window, as is the way of these strange days, that there’s still hope for its resurrection.

“Tristan and I share the belief that the theme we’ve chosen could not be more relevant, and will continue to resonate,” he explains.

From fires to floods, and rising sea levels to global pandemics, Australia, her neighbours and the world at large have to think differently.

“We need to have much, much better ways of embracing our neighbours, embracing culture and living together,” Wong adds.

The projects they selected are for the Australian Pavilion, “representative of a really thorough, rigorous, considered process of design and engagement with Indigenous communities,” he says.

And that means having some difficult conversations. “Architecture has certainly been complicit in the colonial project, and so the residual effects still resonate to this very day,” Greenaway says.

“But what we’re seeking to do is take an approach that is strength-based, which moves beyond the deficit discourse to recalibrate and understand that there is deep wisdom and understanding and sophistication as it relates to Indigenous knowledge systems.”

In|between embraces First Nations knowledge, and notions of collaboration and resilience.

“Forward-thinking and understanding the depth of history that resides in this place,” Greenaway says.

“It’s always been done in a way that has been predicated on caring for country, of considering and understanding the importance and centrality of people and understanding a holistic approach to what I often call Indigenous design thinking.”

The power of well-considered architecture comes with responsibilities and obligations, he argues.

“Through a collaborative model of engaging with traditional knowledge and understanding, we can actually be part of the solution.”

Wong says he and Greenaway share an optimistic approach.

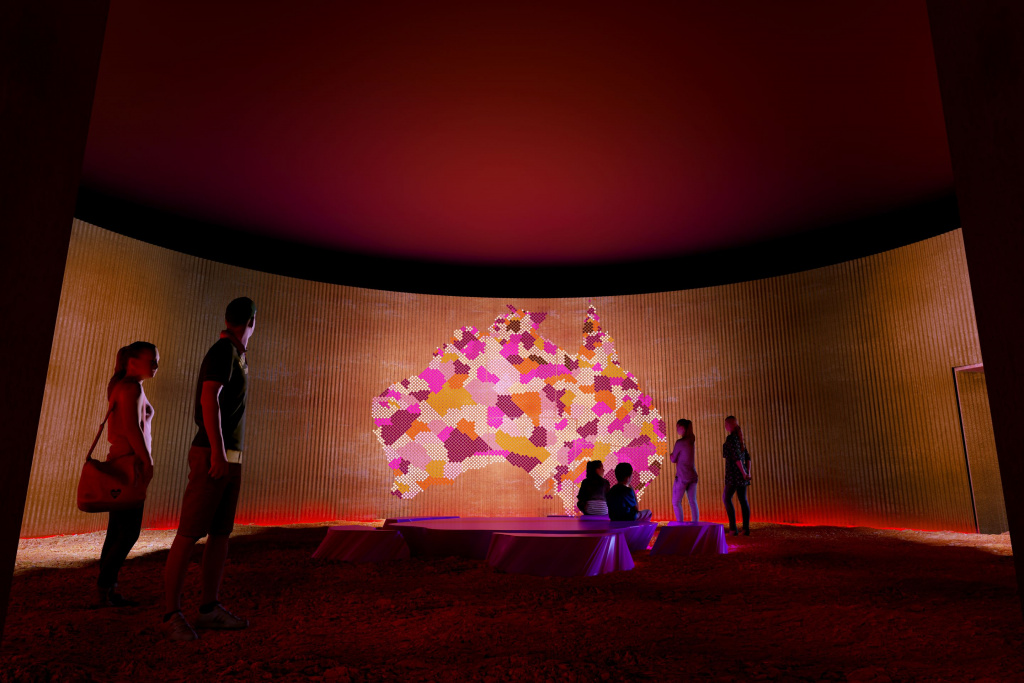

“It’s interesting to reflect on colonial settlement being 200 or 300 years, and Indigenous caring for and living on the land being 60,000 years. The two numbers are at opposite ends of the spectrum. In the Australian context, there are some 600 dialects across 250 language and Nation groups, and that alone is incredible. If Indigenous communities could live in all parts of Australia, those that are incredibly remote and those by the coastline, and live sustainably for that long, then there are lessons there.”

Greenaway says there’s an acute appetite to engage with Indigenous voices into the built environment.

“What we’re seeing a lot of now is a real strong collaborative model. Not only are we engaging with Indigenous design practitioners, but also other Indigenous creatives. So it may well be a sculptor or an artist. There’s an appreciation that Indigenous culture does not pigeonhole relationships. Between country, culture and connectivity, it is a holistic, integrated understanding.”

While it’s true that the cohort of Indigenous architects is growing in Australia, Greenaway notes the numbers are still fledgling.

“If the starting premise is that all projects built in the Australian context are built on Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander lands, then we all have an opportunity and an obligation to acknowledge that starting premise. And to use that as a vehicle for not only developing a culturally responsive design process, but also to step through a methodology that is inclusive and amplifies and celebrates an Indigenous voice into projects.”

In|between encompasses grand and humble spaces, including those from countries like Samoa, Fiji, Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands.

“Many of the projects on these islands and territories don’t get a lot of recognition, and yet the process of design that’s gone on behind them, the way those architects have engaged with their local communities, is incredibly rich,” Wong says.

“[These are] outcomes that aren’t superficial in their engagement with Indigenous communities, but go to real lengths to understand the culture, to listen to the local community.”

Of the over 100 submissions from seven countries, around 20 percent involved an active Indigenous practitioner.

Greenaway says the Australian Pavilion looked beyond the “whiz bang-ery” of an exhibition of this type towards, “the enduring conversation that hopefully will resolve as a consequence”.

It all comes back to shared humanity, Wong says.

“What we’ve found, through this incredible kind of research piece really, is that there are continuous parallels in the stories, in the way that people have gone about designing projects. So what we want to do is position them according to a series of chapters. And those chapters may be along the lines of place and country, language, history and memory. Although the projects may be thousands of kilometres apart, with very different designers, context and Indigenous groups, there are things that bind responsive, considered design.”

And that’s worth celebrating on the global stage, Greenaway insists.

“The centrality and importance of connecting to people is pivotal to what we do. And while we create places and spaces, it’s really about understanding the way in which people seek to live. How we can improve opportunities in terms of creating environments. We know that there are direct correlations in terms of well-being and well-designed spaces.”

We are all on a learning journey, he says.

“You’ll see through the projects, when they become revealed over time, that these practitioners are grappling with a lot of interconnected issues, but they’re doing it in a very considered and nuanced way. And what that also means is that we start to move beyond the standard tropes, the clichés and stereotypes of how we connect to our shared culture to actually embrace an unashamedly contemporary experience. It’s using design as the tool for creative problem-solving.”

Images courtesy of SJB.

You Might also Like