In conversation with: Carme Pinós

In conversation with: Carme Pinós

Share

Carme Pinós is one of the world’s most celebrated architects. She has been an international fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects since 2012 and her most lauded projects include the cube ii towers in Guadalajara, Mexico. But 27 years ago she was completely alone, trying to recover from a broken marriage and professional partnership and start her own practice with just a few tools to her name.

Walter Burley and Marion Mahony Griffin, Alison and Peter Smithson, Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio… the fact that these names are so familiar indicates perhaps that they were the exception that proved the rule. Couples working in architecture in the early and mid parts of the 20th century were fairly rare beasts. And in Spain following the Civil War and World War II even more so, as the country found itself isolated politically and economically under the repressive regime of General Franco.

Following Franco’s death in 1975 and the country’s return to democracy, however, the conditions were ripe for an up and coming couple of architects to make their mark. Graduating from Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Barcelona in 1979, Carme Pinós went back to the school to study urbanism a couple of years later. In 1982 she formed a partnership with her husband Enric Miralles and their studio quickly made a name for itself.

“It was the beginning of the democracy in Spain,” says Pinós. “The government gave us lots of opportunities to build practices through competitions. “After Franco, there were a lot of things to do. A lot of sports centres, libraries, schools, hospitals… and we felt very free, supported by the ambience in Spain at the time,” she adds.

The couple saw international success with projects like the Igualada Cemetery Park (which they delivered via a competition) and the Archery Buildings for the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games. But after a prosperous decade, the couple split both personally and professionally. Miralles went on to marry another architect, Benedetta Tagliabue, before dying at just 45 from a brain tumour in 2000.

Pinós formed her own practice – but the challenges of setting up as a woman on her own were significant, she recalls. “It was very tough,” she says. “It was not easy, absolutely not easy. It took me a lot of time for people to believe in me – other professionals, but also the clients. I had to work alone, with very few tools. But I kept going ahead, because I had a lot of faith in myself.”

With Miralles, she was good friends with Peter and Alison Smithson – one of the few other married couples working in architecture at the time. She describes them as her ‘reference’, but found that as soon as she and Miralles went their separate ways, she became invisible.

“All the photos, all the cameras were for Enric,” she recalls. “And I disappeared completely. But I’m here. I’ve come a long way. Now it’s a little different, but it’s still not easy to be a woman alone.”

Even when she was with Miralles, she often found herself sidelined. In meetings clients would address her husband and ignore her. “Absolutely,” she says. “It’s a lot of years ago, more than 30. No, I didn’t exist. But also it’s our fault. In a way, women must learn to impose, to make them respect us.”

She got her kick-start from an international firm that came to Barcelona looking for her. “They came to Barcelona and said, ‘OK, here’s Miralles, but where’s Pinós?’ And I was in a hole, working alone. They found me and invited me to lecture in Vienna and take part in a big project in Guadalajara in Mexico,” she says. “This changed my luck.”

She capitalised on this by continuing to enter competitions, and winning them. The design side of her business began to thrive and she currently has between 13 and 15 people working for her. The administration side of her own practice, however, is something she has never been comfortable with.

“I have no idea of money,” she stresses. “No idea of what money I have, how much each project costs. I don’t want to know that.” Instead, she has a trusted financial manager, who “controls all the money, all the projects, all the contracts”, leaving her free to concentrate on what she loves: designing. With a considerable amount of lecturing thrown in.

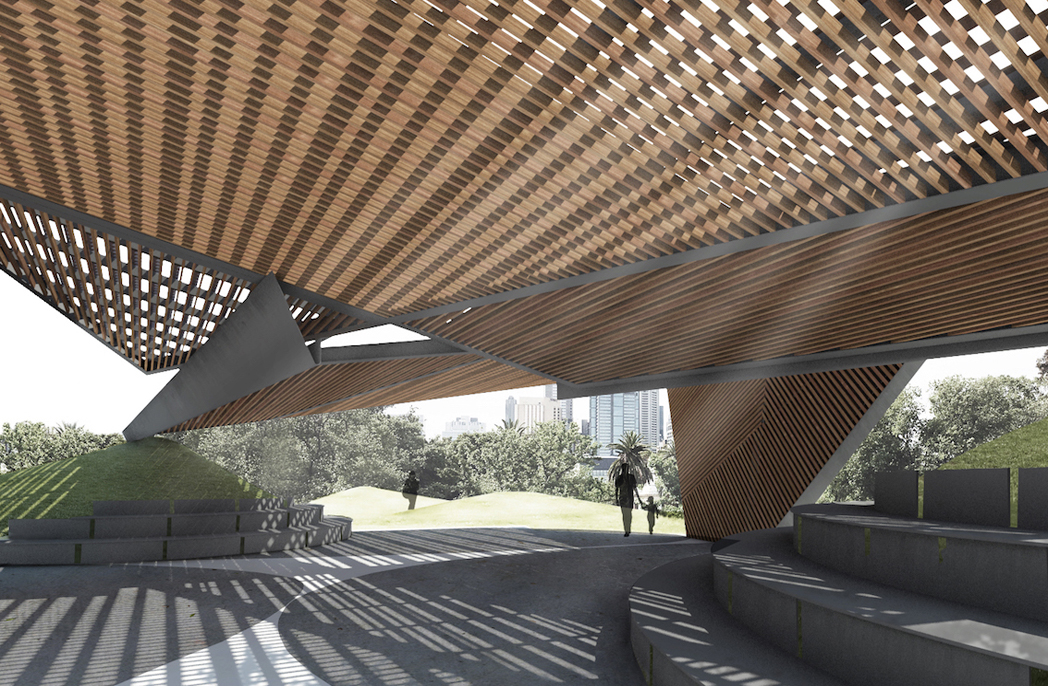

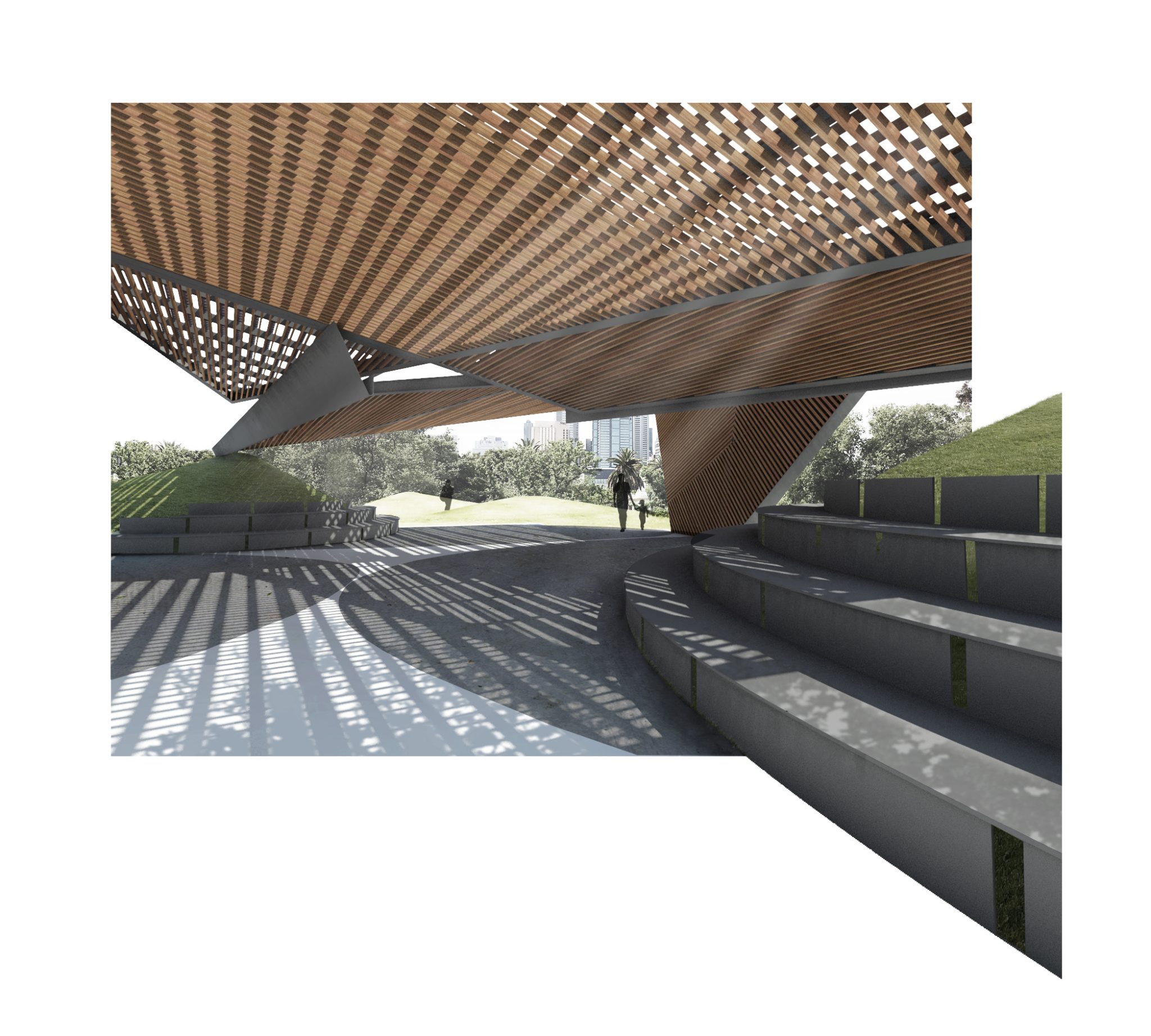

MPavilion 2018 by Estudio Carme Pinós

“But my head is always in the studio,” she says. “The first thing I did when I arrived here [in Australia] was to contact my studio in Spain. With WhatsApp I can make a sketch and send it quickly and I also have some projects under construction. People can send me photos at the end of the day – I’m in constant touch with them.

“At the moment, I have one person working in France, another in San Francisco, another in Mexico…”

Unlike many of her peers, she doesn’t need to tout for business, she says, and isn’t too affected by the vagaries of the economy. “All my big projects arrive through competitions,” she explains. “I have a reputation and I get asked to take part in restricted competitions.”

Strategic thinking has never been a focus, although she admits that she now has some semblance of a five-year plan in place. “I have a little one,” she says. “As I have to be more responsible now. I’m focusing a lot on Mexico and on France.”

Public housing has become a particularly important typology for the practice, with multiple projects in Spain, Mexico and France (Pinós is a dual national). She compares the opportunities in Guadalajara to those in some parts of Australia. “It’s growing and changing the model,” she says. “It was a spread city like Melbourne, but now it’s starting to be more dense.”

But wherever and whatever the project, Pinós says that she trusts her team completely. “I control it when something goes wrong,” she explains, “but only in the last moments of construction is my presence constant.” Up until then everyone at Estudio Carme Pinós is in the same boat. She’s just the captain of that boat.

Carme Pinós on…

Leadership qualities. My rule is respect. I try to give space to people, to convince them that we are in the same boat, but they must believe this. My goals are their goals.

Current economic challenges. I’m looking abroad, out of my country. I started working in Mexico 20 years ago and I’m now focusing there and in France, especially with all the political difficulties in my region, Catalonia.

Advice for young architects starting out. It’s not easy for young people because when I was young, the idea of being an architect was more humanist. Now it seems the pressures of the market require a focus on big offices, more standard projects that are anonymous and luxurious, or pragmatic offices. Young people are working on contracts and maybe they have a different boss for every project.

Succession. My studio is like a family. We are 13 people and they have all worked for me for at least 10 years. We are all architects and we work together very well and I suppose they know who will be next in line to lead the way…

Gender. When I started to study, there were 200 students, and only four women. The other women were working for the administration, and very few had their own firm, their own office. And when I worked with Enric, that just didn’t exist, a couple working together. Now it’s completely different.

This article originally appeared in AR157 – available online and digitally through Zinio.

You Might also Like