Designing buildings that speak and inspire — Gerald Matthews on the role of architecture and aesthetics for education

Designing buildings that speak and inspire — Gerald Matthews on the role of architecture and aesthetics for education

Share

“Every man’s work, whether it be literature, or music or pictures or architecture, or anything else, is always a portrait of himself.” – Samuel Butler

For Gerald Matthews, managing director and senior architect at Adelaide-based architecture practice Matthews Architects, these words from English novelist Samuel Butler could not be more appropriate.

As a self-confessed audiophile, Matthews has a heightened sensory perception of sound. Sound may not seem directly related to architecture, but it plays a vital role in the design of educational spaces. When designing such spaces, the auditory element, along with sight and touch, are essential for success. This is particularly true for Matthews, who admits he has “a natural aversion to the idea of reductionism and the oversimplification of things”.

This multi-sensory awareness, combined with Matthew’s admiration for the educational philosophies of British author and international education advisor Sir Ken Robinson and the psychological principle of time orientation, coalesce into his design of schools and higher education facilities that function as more than places for receiving information. They become important educational tools, offering students — and teachers — dynamic spaces that respond to multifaceted psychological needs, and in some cases, literally speak to you.

Architecture as a tool for the development of time orientation

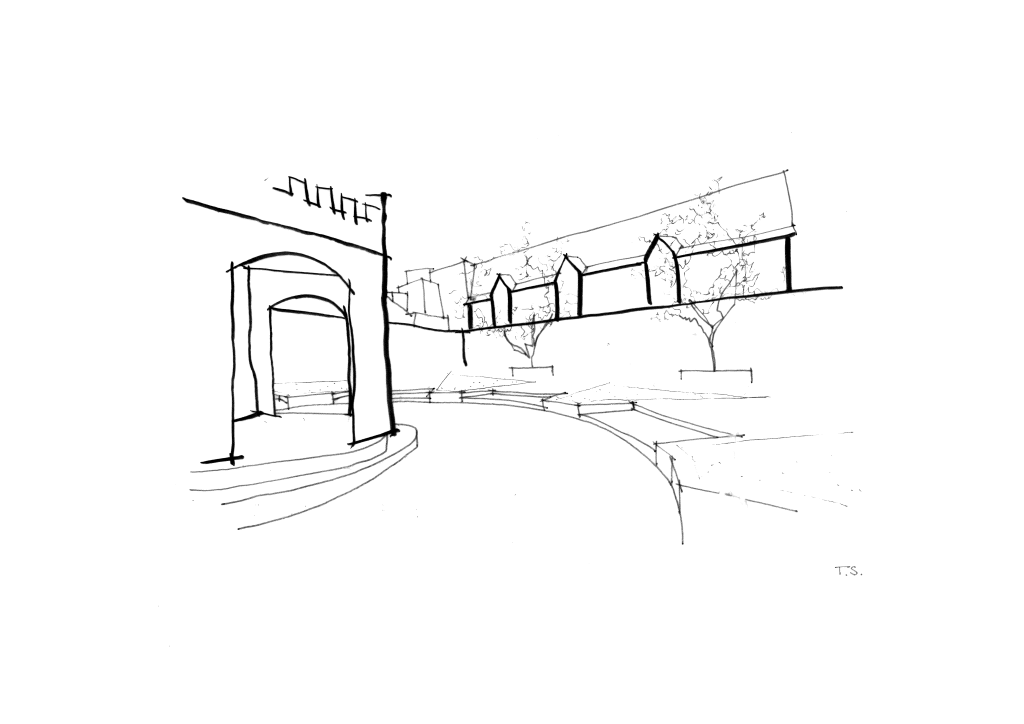

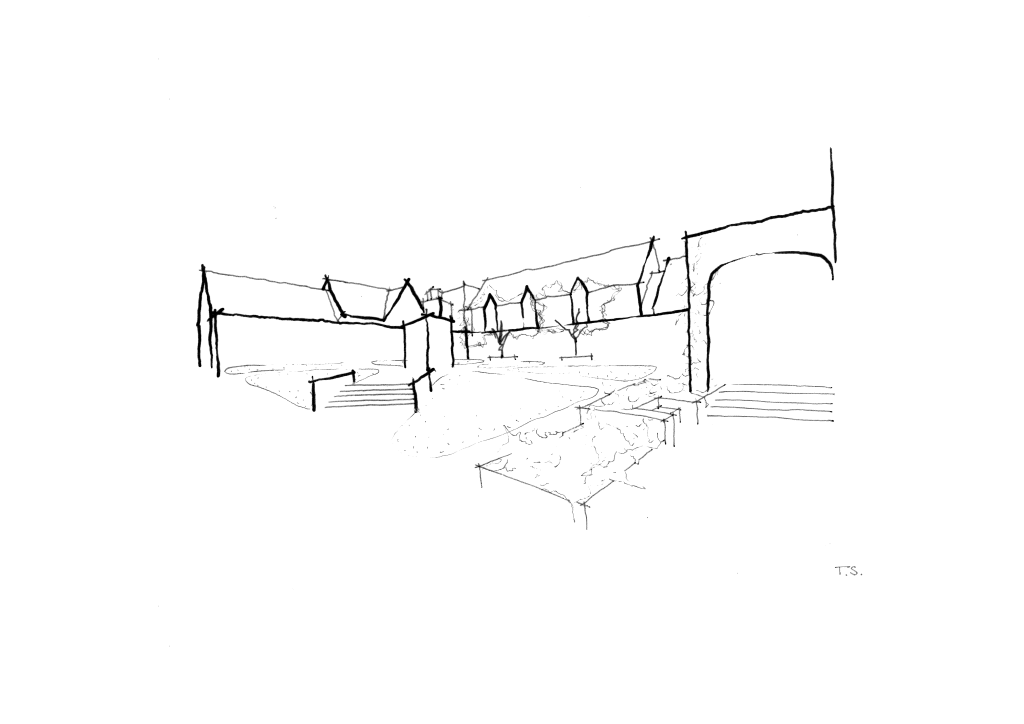

When Matthews Architects was engaged by St Peter’s College, Adelaide, to redevelop the Big Quad and Study Hub, the first question Matthews asked was whether the goal was to create more space for more students, or to enrich the educational experience. With enrichment as the objective, the project provided a unique canvas for Matthews’ architectural skills and philosophies to shine.

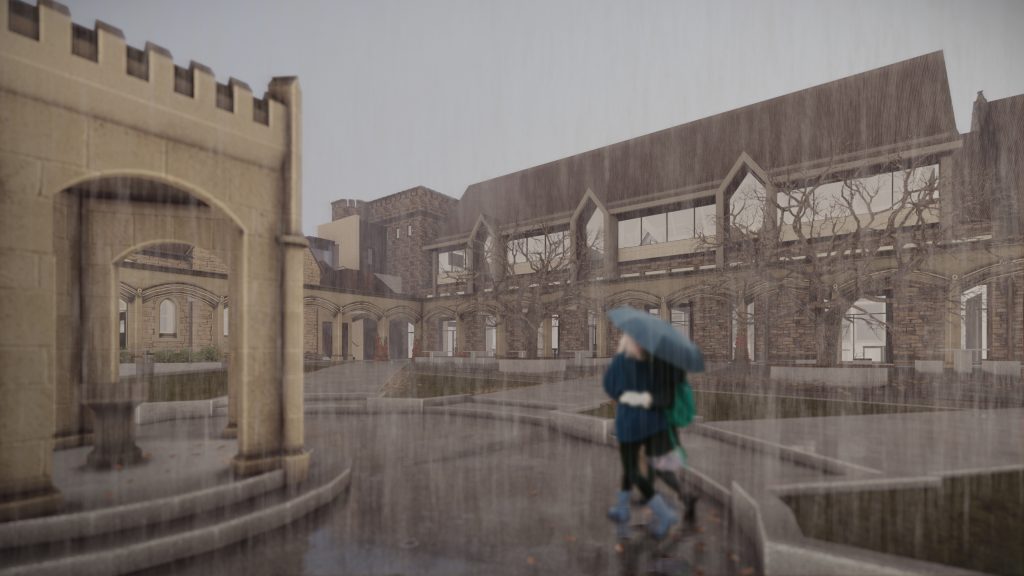

St Peter’s College has a rich history. Founded in 1847, it is one of the oldest all-boys Anglican colleges in Adelaide. The project called not for wholesale redevelopment, but for sensitive unification of the old with the new. It included the reimagining of the Big School room, which was first opened to students in 1850, and the revitalisation of the Big Quad to integrate seamlessly with the Big School room and other teaching facilities. Physical building considerations aside, the client had an additional, arguably more important element to their brief: how can the architecture of the school environment itself support Year 12 students as they prepare for their final exams?

It’s here, at the intersection of complex architecture and the complex needs of students who are at an important stage in their educational and psychological development, where Matthews excels. “The complexity of humans is similar to the complexity of architecture,” he says “This is why educational architecture is so fascinating to me because what’s going on inside the individual people that you’re designing this for is incredibly complicated. Especially, I would say, during the teenage years.”

With an awareness of the anxieties, social dynamics, and pressures faced by Year 12 students in mind, Matthews drew upon his decades of design experience, psychologist Philip Zimbardo’s research into the way our experiences of time are shaped by our physical environments, and the concept of time orientation to inform the design approach.

Time orientation is an unconscious yet fundamental cognitive process which develops over the course of childhood and solidifies in early adulthood. Through this process, we shift from being only aware of our present, immediate needs, as all babies and young children are, into being able to conceive that there is both a past and a future. This framework allows us not only to organise our personal experiences, but to act and make decisions in the present, with our future selves in mind.

While this is a complex area of psychology and human development, from an architectural perspective, Matthews considered how he could shape the built environment of the Study Hub and enhance the existing structure of the Quad — which is 60 percent outdoors — to assist the students with developing a sense of time orientation. Or, simply, how do you convince a teenager who would rather play PlayStation than study to develop a future orientation? “It’s hard to convince yourself to practise with your sports team and it’s hard to even plan for the future,” Matthews says. “So, part of the process of education is to help kids go from a present orientation to develop a future orientation. If you want someone to plan ahead, you have to show them the passage of time.”

Beyond the classroom: Integrated educational environments that guide and shape experiences

To support the students with this important developmental process, Matthews looked to the natural world and the senses, and considered how architecture and design could be used as a harmonious instrument. The Study Hub’s steeply pitched raincloud grey corrugated steel roof and its triptych cathedral-like, floor-to-ceiling steel-framed windows emerge above the original stone building. What’s most significant about this building is not simply its sympathetic aesthetics, but also its sustainability features. Matthews believes in retaining and enhancing original buildings whenever possible.

The most significant design decision here is the deliberate northern orientation of the windows. “Through a northern window, you’ll see the sun literally over the course of a day move from one side to the other. You see the shadows move. If you’re trying to persuade someone to think about the future and plan ahead and, you know, you’re running out of time, or let’s map out what you’re going to study for the next five hours, expressing the passage of time is incredibly important. That’s across a day, but the Big Quad project also expresses seasonal time.”

In allowing natural light in — showing the students that time is of the essence — the project goes beyond circadian rhythms. There is no tricking the body into thinking it’s day or night, as one experiences in a casino or shopping mall. Instead, the students experience a day as it is, and they also experience the changing of the seasons.

As seen in the concept renders, once the young trees have grown, students will be greeted by verdant trees in full leaf in summer and watch as the leaves turn shades of red and orange, falling to the ground, only to come back to life in a burst of blossoms in spring. They’ll also experience the elements as they cross the Quad. Once again, the seasons, architectural programming, and schematic planning all work together in powerful ways to enrich the education environment and experience.

This may seem obvious, but it’s at once a subtle and powerful visual and physical cue, which is especially potent in Adelaide. “One of the good things about Adelaide is it does have four very distinct seasons, so that helps us,” Matthews says. “It would be a very difficult, different, and far harder thing to achieve if this project was in the tropics.”

Buildings that tell you what to do

Matthews didn’t rely entirely on the senses of sight and touch to enhance the design and achieve the goal of supporting the development of time orientation. He also used sound, acknowledging that to learn and study well, one needs quiet, but not isolation.

“If you imagine a whole cohort of Year 12 students all studying, [it is] essentially optimising [the space] by having self-directed study that is in pace with where they personally are up to,” Matthews explains. “Study groups are useful, but you can’t do all of your study in a group. The individual journey is important. You have to learn at your pace, and in your process.”

But he says studying at home in a bedroom or in an individual study space somewhere, or even in a library corral can be socially isolating. “Social interaction overstates it, it’s more about human adjacency that I think is comforting to us, so the Study Hub is built with this idea,” Matthews says.

The layout of the multi-level Big Quad incorporates the Study Hub, break-out spaces, communal soft seating conversation areas, individual study desks, a larger boardroom-style meeting room, interactive classrooms, and a large assembly hall. None of these spaces are unique to St Peter’s College. What is special about them, however, and in particular the Study Hub, is the design of entry and exit — one long space with a walkway down the middle, which can only be entered at each end.

“We want[ed] it to be noiseless when people enter,” Matthews says.

Outside these study spaces, the cacophony of students coming and going and chatting is a natural part of school life. The challenge for Matthews was how to nudge the students to transition from interaction into inward focus.

“We needed to signal to people to lower their voices and then stop talking as they enter,” Matthews explains. “What we created was essentially an acoustic tunnel that absorbs a huge amount of the sound, so as you’re walking through it, it feels very quiet…. It’s one of those self-fulfilling moments. We wanted to make people notice the little ‘shh’ that the building gives you. These tunnels are the building’s way of saying shh.”

At approximately four metres long, the tunnels not only have acoustic properties that signal to students they’re now transitioning from the outside world of exuberance and distraction and into a space that calls for calm and focus, but they also have spatial properties that alter the physical experience.

Each tunnel is exactly that — a tunnel. With dark panelling on the ceilings and walls, a lowered ceiling height, and a width that only allows for walking in single file, it’s as if the building itself takes each student by the hand and gently guides them into the right place and mindset for ideas to germinate and life-long lessons to take root.

Simplifying complexity: A simple answer, not a simple question

With the design of St Peter’s College Big Quad and Study Hub, Matthews and the team at Matthews Architects have achieved the almost impossible. They’ve made a very complex thing simple. It is simple, perhaps even innately obvious, for an architect to look to the natural environment and the human sensory experience to inform the design of a building, which is made for people and must withstand the whims of the elements. But, it is rare that all these elements come together so elegantly in one project.

“The process of making a complex thing simple is not about being reductionist,” Matthews says. “It’s not about trying to distil the complexity down into something that is the barebones or lowest common denominator version of something. Our approach to complex projects is to embrace the complexity. The design process is the process of creating a simple answer. The goal is not to make the question simple. The questions will stay complicated.”

Answering complicated questions through design, with an attention to detail and the real, genuine needs of those who use the spaces, is what makes Matthews one of the industry’s leading education architects. His personal passion for classical music and interest in developmental psychology provides him with a keen awareness of the interplay between architecture, acoustics and people.

If the St Peter’s College Big Quad and Study Hub are, as Samuel Butler suggests, a portrait of Matthews, it is also one that resonates with the rich history of the school and the bright, optimistic faces of all the St Peter’s College students, past present and future, whose lives will be shaped by the tangible and intangible qualities of exceptionally thoughtful architecture.

Photographer: Aaron Citti.

Concept renders and sketches supplied by Matthews Architects

Check out ADR’s Q&A with Gerald Matthews of Matthews Architects

You Might also Like