Vertical Glass House gives a view of the sky

Share

All images by Hengzhong Lv.

Along the west bank of Shanghai’s Huangpu River, set within Longyao Riverfront Square promenade, stands a 13.5-metre concrete tower. The thin bunker-like building, with rows of horizontal slit windows, appears ready to take on invaders from the Huangpu or, perhaps, the nearby skate park. But the exterior is deceptive. Upon opening the heavy steel door at the entry there is a rough facade, like that of a geode, at first concealing then revealing a light-filled interior. Yung Ho Chang / Atelier FCJZ’s Vertical Glass House is in fact anything but aggressive. Instead, it is an inward-looking residence, both physically and metaphysically.

Structural members are accentuated and act as partitions between living spaces and vertical circulation.

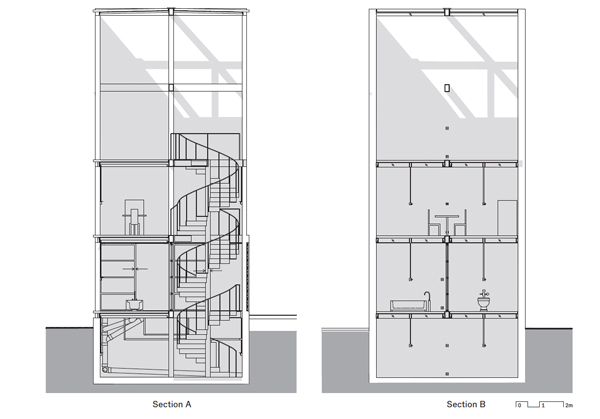

The ‘glass’ of the building’s name refers to the green transparent material of the floors and ceilings that run from basement to roof, offering a continuous interior view from earth to sky. Rooms move from corporeal to ethereal as one ascends through the house: mechanical systems occupy the basement; bath, toilet and clothes drying the first floor; kitchen, dining and bedroom the second; and an empty, double-height space the third. The glass throughout creates a mise-en-scène of people within. Whether contemplating the universe under the clear roof or fussing with the water heater in the basement, visitors’ activities are visible from every point in the dwelling.

The building’s plans, like its sections, are composed of simple geometries. Each square floor, with a footprint of less than forty square metres, is cut into sections via steel beams that intersect at a central column. Stairs run up the north-east quadrant, plumbing down the north-west.

Steel furnishings designed by the architects are placed centrally within the quadrants. The scheme’s perfectly composed rectangles might seem like a study of classical dimensions, something produced centuries ago at L’Ecole des Beaux Arts. But the contemporary building materials, along with a new refrigerator and IKEA mugs by the sink, bring the visitor back to today. A quick visit to the small house offers a simple reading: a stimulating view up through the minimally furnished floors, a spiralling ascent on a steel stairway and a somewhat anxious glance down (for those with acrophobia). Actually occupying the space produces a very different experience. Beijing-based architect Chang, co-founder of Atelier FCJZ, spent two days in the Vertical Glass House with his wife and partner, Lijia Lu. The glass suggested to him an omnipresent viewer, he says, and so each simple action he took within the house became ritualistic.

The insular nature of the building, with minimal fenestration on its elevations, allows for diffuse light to filter through the building.

Atelier FCJZ states that the project is ‘a critique of Modernist transparency in horizontality’. The Vertical Glass House can be compared to Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House, turned on its head, from a rancher spread out on an Illinois lawn to a tower in über-urban Shanghai. The building is also turned inside out. Mies’ voyeuristic glass facade is mimicked in FCJZ’s floors and ceilings, with its interior privacy walls here reproduced as exterior walls, shielding views from not-yet-existent

next-door neighbours.

The house’s not-distant neighbours include new complexes of residential towers, with names such as Venezia Shanghai Riverside Garden. Other neighbours are former industrial and aviation buildings that are in the process of being converted into cultural centres; two recently opened centres of contemporary art include the Yuz Museum and Long Museum.

Both sets of buildings are part of the West Bund, a 1740-hectare redevelopment site. In 2013 the first West Bund Biennale of Architecture and Contemporary Art promoted art and design as catalysts for the area’s redevelopment. Chang was a curator of the biennale and he built the Vertical Glass House as part of the event and to attract future experimental projects.

The Vertical Glass House design originated long before the 2013 biennale, however, designed by Chang in 1991 (two years before he opened Atelier FCJZ) for a housing competition organised by the magazine, Japan Architect. Copies of his 1991 drawings now hang on the walls surrounding the dining table of the completed house. The design of the building changed little from these drawings to its execution by FCJZ, with minor modifications to windows, plumbing and air-conditioning. The lack of change corresponds with the notion that the building is siteunspecific. Instead it is a realisation of a concise twenty-two-year-old idea. While the house does share elements with FCJZ’s current work – most notably its focus on materials – it is more akin to other, earlier studies that critique the Modernist square.

Think of Peter Eisenman’s 1975 House VI or Bernard Tschumi’s 1987 Parc de la Villette. The Vertical Glass House shares their focus on geometry-driven theory over inhabitation. One might say that the Vertical Glass House is as much a folly as Tschumi’s park structures and more a landmark than an actual home. Chang says that the house will be used as a temporary home for visiting artists and architects during the next West Bund Biennale of Architecture and Contemporary Art. For now, it stands empty in its park setting.

Must the building be occupied for it to be considered a real house? If so, then the purchased-but-uninhabited units of Venezia Shanghai Riverside Garden and so many other Shanghai apartment complexes would not be deemed houses. They dot the city with empty rooms and standardised layouts that have no potential to infl uence design or inhabitation. Instead, they say to Shanghai that there is only one viable, real estate-driven model for housing.

The Vertical Glass House – folly or not – suggests that the house is a building type that can be explored endlessly and creatively.

Review by Clare Jacobson for Architectural Review Asia Pacific.