Super-Sydney: density, urban types, public places

Super-Sydney: density, urban types, public places

Share

Above image: Sydney Harbour from above. Photography by Rodney Haywood

In 2007 the United Nations identified that, for the first time on record, more than fifty percent of the world’s population would be living in urban settings (UN World Urbanisation Prospects report 2007 review). Australia already has one of the highest rates of urban living in the world and this will continue to increase as our population grows towards 50 million people by 2050. Because urban living is defined as non-rural, it should be noted that while Australia’s population is relatively concentrated in urban areas, these figures include substantial suburban areas defined as metropolitan.

Urban densification, however, is an issue that seems to rankle many Australians and the notion of increased density would only be palatable to the Australian populace if it were accompanied by more appropriate urban planning typologies, as well as civic centre improvement. Across Australia cities need to get bigger and better, not just bigger and bigger. The question should be one of civic value rather than commercial property price and urban scale. In localising the argument to Australia’s most expansive city, Sydney, the focus seems to be on the latter, with discontent felt throughout the community, a point evidenced by the recent rejection of the New Planning Act in New South Wales (NSW) – led by particularly well-organised community group action networks. It is prescient then to open up discussions on the institution of new urban typologies, which more adequately restructure cities that better reflect current modes of living and work, as well as civic improvement.

The growth of Australian cities cannot easily be compared with other cities. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (June 2011), the NSW estimated population reached 7.3 million (one third of the national figure) and is rising at a rate of 1.4 percent and while this is a significant growth rate, it pales in comparison to the Asian equivalent. Singapore, for instance, is growing at 2.5 percent per annum, but it is in China where the most dramatic upturn in growth is noted. The urban migration from rural to urban living is unprecedented in such a short period of time.

Interestingly, since the economic reforms began in 1978, all of China’s population growth has been urban. It is unparalleled that over the period since the reform, 470 million people migrated to urban areas. Hefei, in the province of Anshui, has seen a 102 percent increase in population in the last ten years, elevating it to a place of economic importance where before it was a rural town. For China even the label ‘cities’ could be inadequate, given the growth rate and sheer scale, it is more appropriate to label these areas as ‘urban regions’. It is almost unfeasible to compare Australian cities, with the exceptional urban agglomerations happening in much of Asia, but the comparison lies in the fact that both are experiencing urban growth as a result of a migrating workforce.

Sydney’s growth rate will no doubt continue to rise exponentially, as long as urban migration remains a priority for state and federal government. A cause and effect relation of urban growth and migrant workforce can be seen in the increased salaries and disposable income, resulting in larger dwellings for smaller households – with Australian households now infamous for residing in the largest dwellings in global terms. Such economic and population growth factors have resulted in spread, or suburban sprawl, rather than consolidation, with a low-rise, low-density typology predominant.

More recently Australian cities, in accordance with government policy, have started to ‘intensify’ in vertical scale and density rather than continue to sprawl. In Sydney, such urban intensification is increasingly unpopular to the more conservative sections of society, believing that as Sydney intensifies, the city ‘gets worse’, with more congestion, much longer commutes, less open space and perceived overdevelopment. The challenge, then, to the architecture discipline is to enable and facilitate high quality urban renewal rather than green field spread, in order to change the tide of public opinion.

Re-thinking urban typologies

As Sydney has continued to grow, urban strategies attempted to rein in the spread of the city, most notably the 1948 Cumberland Plan (based on the London Plan) is a case in point. It defined the metropolitan area and surrounded it with a green belt, intended to contain urban spread. However within twenty years, changed government policy allowed development to breach the ‘green belt’ initially intended to contain Sydney’s ‘edge’ and encourage ‘filling-in’ the underdeveloped areas within the centre. The ‘containment’ concept was replaced by the ‘transport corridor’ or ‘finger’ paradigm, as proposed by the 1968 Sydney Regional Outline Plan (SROP), which was based on the Copenhagen Plan. Development could spread along the rail corridors and the newly identified northwest and southwest ‘growth areas’. Both urban strategies – the contained plan and corridor plan – vouched for ‘district centres’, where development would be concentrated at relatively conflated nodes. Over time the ‘district centres’ strategy developed into a more sophisticated urban policy, with its impact stretching from regional to local.

Metropolitan Sydney remains the economic centre of Australia in terms of business and employment opportunities, but the City of Sydney has offered a further option in its development: the ‘city of villages’ notion taken from the City of London and New York City’s boroughs concept. Sydney’s metropolitan strategy however is dispersed, with regional cities within metropolitan Sydney, such as Parramatta, Liverpool and Campbelltown. While this structure may reduce infrastructural pressures, it surely does not address the need to move away from the tendency for suburban sprawl. Current government policy assumes that these regional centres will become specialised industry zones, but as the nature of work continues to change, it is not at all certain that such regional centres will continue to attract jobs in sufficient numbers to serve their subregion.

City planners need to learn from previous urban policy failures and to understand the changing nature of industry and the geographic drivers. A future Sydney may be better served by these metropolitan regional cities, as well as clustering expertise and industry sectors to a local level, such as health, research, manufacturing etc. This would entirely depend, however, on well-connected transport corridors, with a mix of housing and service sector jobs. A less rigid and segregated model may be required if cities such as Sydney really want to ‘fill in the gaps’ rather than spread.

Over the last two decades, these clusters of expertise, such as research, health and education, have developed. These have not been ‘designed’, but have emerged as universities and hospitals, attracting high value jobs, as well as technology companies.

Prominent examples of clustering or agglomerations of activities in Sydney include major civic and health projects, such as hospitals or universities, notably Westmead Hospital in Sydney’s west, Macquarie Park/Macquarie University in the northwest, the University of New South Wales/Prince of Wales Clinical School and the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS) and the University of Sydney/Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and the Australian Technology Park at Eveleigh. Each centre is a rich and diverse place. Further, the UTS precinct has stimulated nearby projects such as One Central Park, which includes projects from Ateliers Jean Nouvel and Sydney’s Johnson Pilton Walker.

A more complex, less geometrically ‘pure’ form of clusters, corridors and centres are emerging. Rather than the traditional planning model, a network or ‘mosaic’ of places connected by public transport is developing. The current NSW government priority on infrastructure enables opportunities to build on this strategy, but its long-term success is dependent on successful and considered public realm improvements.

Public realm improvement

To institute successful public realm or to develop existing public areas, planning authorities require significant financial investment. Whether this is government-funded or deriving from the private sector, it remains a subject of debate in most states. However the provision, preservation and maintenance of the public realm in light of increasing urban density are paramount and of bipartisan importance. Traditionally, public places have been a government provision; yet as economies deregulate, privatise and globalise, this provision will increasingly be a private entity. It will be interesting to note the changes in the vitality of the public realm as it shifts ownership to the private sector.

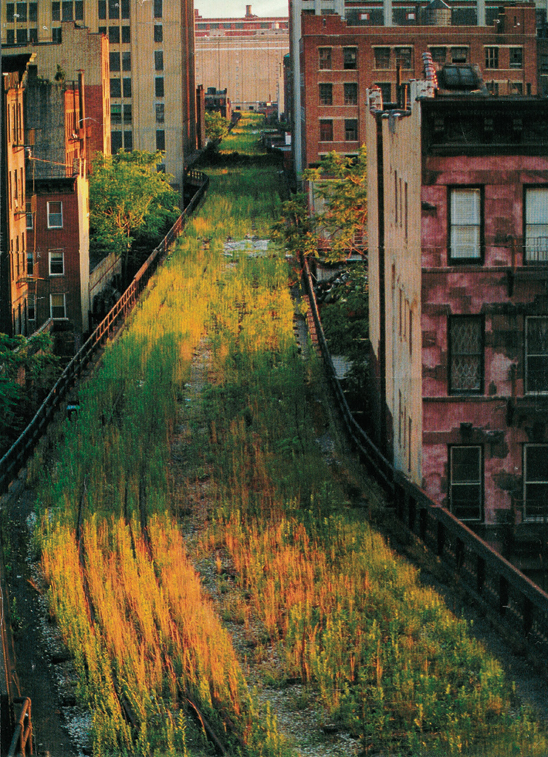

The very significant public realm improvements in cities such as New York and Chicago are notable in this regard. Initiatives such as New York’s notorious High Line have improved and increased the public domain. The High Line hybridised the public–private investment model, with funds from state, city and private entities. Indeed, Friends of the High Line, a community body, had to take legal action against the city’s mayor in a bid to preserve the existing, dilapidated structure. It resulted in the city investing USD$33 million and the community fundraising USD$50 million to procure the project and ensure its continuing development. Such action plans for civic and urban improvements are rarely noted in Australian urban centres.

As Sydney grows it will become increasingly important to maintain existing public space for public use, as well as providing new public realm. Like the US, it is unlikely that this will happen without the private sector and community philanthropy. A solution may be for strategic plans to mandate the private provision of public places in major new developments, with an insistence on publicly accessible amenities.

It is noteworthy to understand the types of public places in Sydney at present and to underscore the developing areas in order to establish how the city can maintain its urban vitality in an age of densification. There are a number of place variants: public, infrastructure, mercantile and ceremonial.

Public places are those that were previously publicly owned and funded, such as Bloomsbury Square, London, UK, or state-owned and funded such as the Tuileries Garden, Paris, France. In a capitalist, developed world, the model has shifted, as noted. In Sydney, the aforementioned One Central Park, as well as the forthcoming Barangaroo, designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour and Partners, identifies a move towards private investment, with the possible reduction of public realm.

Infrastructure places, nodal transportation hubs, are key components in a city’s success and for the enjoyment of its citizenry. Public places are entirely dependent on the need for infrastructure, the inclusion of major and minor railway stations, ferry systems, street formations and designated cycle paths. Future infrastructure projects in Sydney should mandate transport nodes to incorporate covered public realm as a basic factor in the formation of the design brief; for example, public places should be within 250 metres or a three-minute walk from a transport node and incorporate shared (bicycle/pedestrian/landscape) pathways into existing transport corridors.

Mercantile places are those with trade activities, notably marketplaces. In the European centres of Rome and Paris for example, it is mandated that fresh produce markets are available in urban segments. Such urban epicentres require a certain amount of space, but are also dependent on accessibility and flexible ownership and usage. This approach allows diversity in the experience of the city dweller. Can Sydney implement mercantile places more effectively to encourage commercial and retail activity. With the widening of public pavements and thoroughfares the city could activate the urban streetscape and intensify the street frontage, which could impact upon a more diverse and active public realm.

Ceremonial places across religious denomination, such as churches, synagogues, mosques and temples, could be better integrated into the urban fabric by encouraging the cross programming of social or civic activities held at the ceremonial place. This could develop a greater sense of civic or community based public ownership and as such increasing and liberalising their opening and admission regimes to allow greater public access, evolving new and diverse public activities.

Bringing together strategy and improvement

When briefly looking back at the development of Sydney and its potential urban growth, it is important to reflect on the city’s planning failures and to address the need for the provision and maintenance of the public realm. By clustering industry into specific zones, increasing infrastructure and housing provision, as well as issuing mandatory policy stating the requirements for public realm, Sydney could transition from a relatively low-density city into one that embraces the notion of density without the loss of quality of life. Through transit-oriented corridors and egalitarian placemaking, Sydney could become the blueprint for the creation of liveable cities. On a national level, it is imperative that, as densities increase, cities become more absorptive, connected to transport and build on and improve their public realm.

Feature by Architectural Review Asia Pacific contributors, David Holm and Philip Graus.