Howard Raggatt speaks on Mongrel Rapture: ARM’s award-winning text

Share

Taking out the highest honour at last week’s Victorian Architecture Awards, ARM’s richly layered work on the Galleries of Remembrance garnered the prestigious Victorian Architecture medal as well as the Melbourne Prize and accolades across heritage architecture, urban design and public architecture categories.

ARM was also awarded the Bates Smart State Award for Architecture in the Media, for their monumental compendium of works, Mongrel Rapture: The Architecture of Ashton Raggatt McDougall, published by Uro Media and edited by Maitiú Ward and ARM’s Mark Raggatt.

ADR speaks to Howard Raggatt about ARM’s motivation behind producing the tome of biblical proportions, described as “required reading” by reviewer Callum Morton in AR140 – Small Spaces (on stands now).

The form of the book explicitly references a religious text – what was the impetus for producing in bible format?

We didn’t really set out to make a bible originally, it just seemed to turn into that on its own, I think. We tended to blow out in size; originally we thought it might be 500 pages, or something. And then by the time we got to 1600 pages, we thought we’d struggle to fit that into one volume! We were researching thin paper and found a company in China that specialised in bibles.

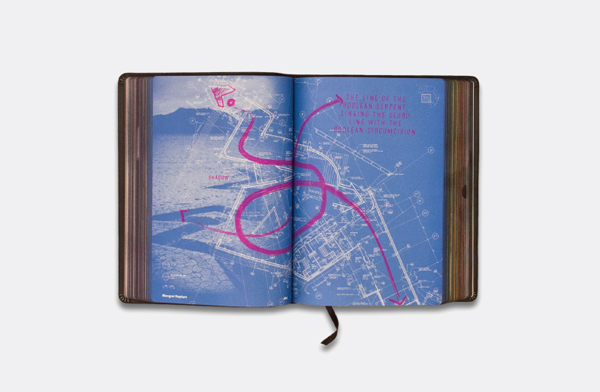

The chapters are probably 200 pages each, and I suppose the colour invokes the idea of the illuminated manuscript. The blackness of the cover related to the interior of it being a spectrum – there’s seven chapters and each is in a different colour of the spectrum. So the cover ended up black so that the interior could be coloured.

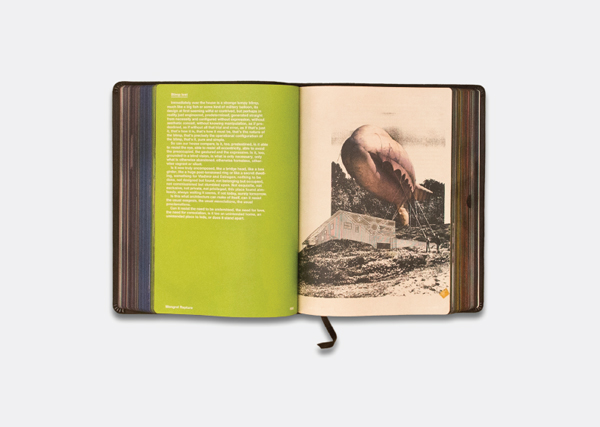

We weren’t unmindful of the fact it would look like a bible at the end – the rainbow text on the cover is possibly a modifier, the title alludes to something other. Our message is fairly diffuse. Yes, it’s a monograph but it’s also a manifesto of sorts. We’d like to think of it as being open to interpretation than just our pronouncements. It doesn’t seek to reduce architecture down to solutions, which I think Architecture is often talked in terms of. We tend to see it as more of an exercise in questioning whether or not architecture is seriously thoughtful and meaningful, or whether it’s only really purposeful and functional.

I guess our tone is that we expect that architecture is becoming more functional and performative than it is seriously cultural. We’d like to think of architecture as something that you try and read, which is something that architecture in some ways seems to be moving away from. So I guess the book has a lot of words as well – about 150,000 words. It’s not exactly ‘snippetty’, there’s some solid material there.

It ranges across various types of text too, so there’s some text that tells a story, others are speculative, lamenting, critical, poetic, drifting into the almost prophetic.

It’s not setting out to explain our work as such, it constantly maybe just uses our work to try and figure out what architecture is, or could be.

So there’s no sense of the tongue-in-cheek, or ‘the architect as God’?

We’re actually not very tongue-in-cheek at all – we’re actually deadly serious all the time. So I think that the reputation for tongue in cheek, it may be a way that we tend to present ourselves personally – maybe the ironic is something that we find hard to resist – but the work itself is definitely not tongue in cheek. The book, I think, doesn’t have that tone. It is surprisingly earnest.

Though hopefully people find that it has a charm about it, I think it does. There’s a kind of glorious, mysterious quality about it, which is not necessarily our doing, but it’s just something in the way it all comes together, I think. It’s almost beautiful

It does have a very commanding presence.

We were told that you can’t sell a book with a blank cover – but of course, that just encouraged us to go with the black. So we do wonder whether anyone’s going to read it!

We like to think that architecture requires considerable erudition. You’d like to think that those who comment or practice architecture are erudite in the field. Increasingly you wonder how that can actually happen. We no longer seem to be interested in history or philosophy, or all the larger arenas of culture that you would have thought are necessary to practice.

Buildings being so material, it takes even more knowledge in order to turn something inanimate into something of meaning, it’s a big ask, I think. We just question that, we’re not entirely sure that it does.

At the end of the days, the buildings that do get built have to be somewhere – and they’re usually somewhere for a very long time. And therefore they should really understand what they are, what ever that means. They aren’t merely products that you can disseminate around the globe, because a building is not just a product. But not everyone agrees with us of course.

Aren’t opposing views just a part of pushing discourse?

Discourse? We don’t use that word any more do we? ARM does, but I don’t know that we do as a society. There’s publishing but there’s not discourse. I think we’re deluding ourselves, or hoping, or wishing that it still exists.

Do you see that as a symptom of a young country?

No not really, it’s a global thing. If anything you might think that a young country would be more likely to be engaged in discourse.

Was there anything you drew from seeing ARM’s works all together in the published form?

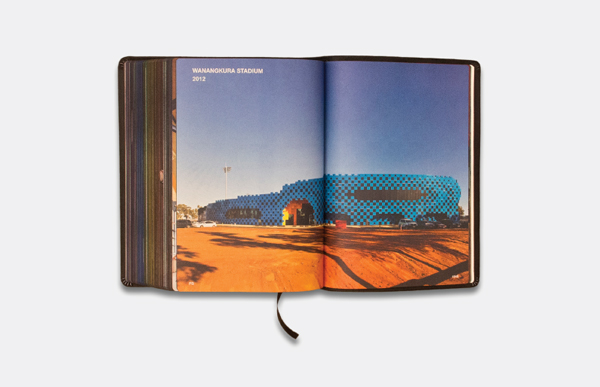

With those seven chapters we’re exploring, or five thematic ones, I guess originally we thought that projects would just fall into a particular chapter, or theme. But what we actually found was that nearly all the projects ran across all of them.

And so that’s how we did them in the book, so that a project might appear three or four times, with a different presentation. That was something that became clearer to us, and once we realised it was happening, we worked with it quite positively.

Also something that Mark has spent a lot of time on, is the timeline we did. There’s a sort of graphic format at the back of the book which has what’s happening in the world at the top of the page, and through the use of colour, we try to connect projects across time, so that a particular project might have two colours or four, according to the way a project seems to touch on various themes.

In a lot of architectural books, every project is presented in the same way, with the same formatting or type of treatment. Whereas we like to think that ours have come out of specific types of zones, and that they’re layered. We’re allowing them to have this flow of interconnectedness, so that they make sense within a wider history rather than existing on their own.

Do we gain an insight from the book into the practice’s own vernacular, in what defines an ARM project?

ARM I think has a high degree of recognisability – and often that’s because buildings look the same, if you think of architects like Frank Gehry or Richard Meyer – there’s usually elements of the building that are recognisable because they’re alike.

Our projects, generally speaking, are not like that. But I suppose we’d like to think that nevertheless, there’s something in the way we derive a project, that it has that cohesive quality about it. And because they derive in a certain way. Some would say they all come out ugly, and that’s how you can recognise an ARM building – but the reality is, if they are ugly, it’s true that we don’t try and fix them. I’d like to think that for our part, we do try and say “well, that’s the way they came out, who are we to fix them up?”

You love all the children equally?

Yes! We love all our children equally.

A full review of ARM’s Mongrel Rapture: The Architecture of Ashton Raggatt McDougall features in AR140 – Small Spaces

Purchase a copy of the book here.