How autonomous transport will shape our cities’ future

How autonomous transport will shape our cities’ future

Share

A unique opportunity exists for infrastructure investment in Australia as transport as we know it faces disruption from autonomous vehicles, says Peter Newman Professor of Sustainability, Curtin University.

Disruption is not a dirty word. Traditional transport models are being transformed for the better by savvy young upstarts: the taxi industry by Uber, for instance, and even bus services by on-demand provider Bridj in parts of Sydney.

Autonomous vehicles will soon be a familiar sight in bush and city landscapes. In New South Wales the transport minister, Andrew Constance, predicted in 2017 that public transport might not be needed in future, certainly with no drivers, because autonomous cars will handle everything.

I don’t think this will happen. The car is a good servant, but a bad master in shaping our city, even autonomous ones.

What will a city of autonomous cars look like?

A fully car-based approach to autonomous vehicles would involve cars driving around suburbs day and night, searching for people to pick up on demand. These vehicles would move into corridors, main roads and freeways, travelling at high speeds with just a metre or so between them.

Increased road capacity, safety and the very real prospect of solar-powered cars are undeniable benefits.

But what kind of city would we have? We would see more urban sprawl, possibly worse congestion and a departure from walkable cities.

We would lose an opportunity to reclaim pleasing city grids and urban centres. These spaces, which our city planners intended for pedestrians, have often been devoured by cars but are now returning to their rightful place as meeting spaces.

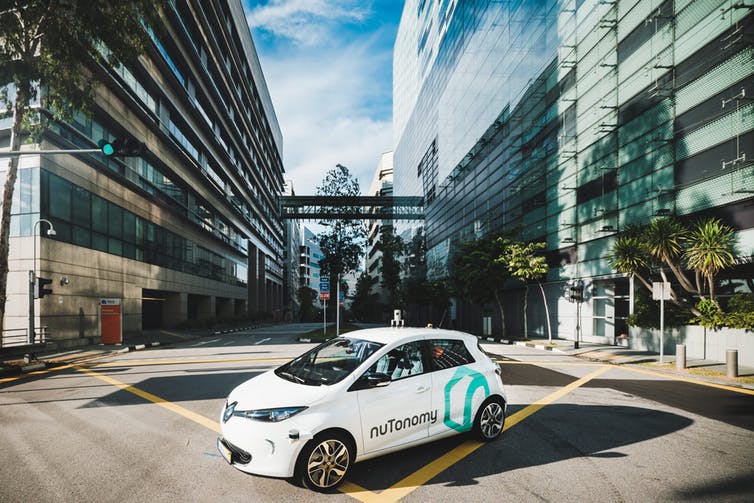

Singapore’s driverless taxi, nuTonomy, in 2016. EPA/AAP

The case for trackless trams

Autonomous transit vehicles with a collective benefit to society offer us a chance to continue to reclaim these spaces by providing rapid shared mobility where it doesn’t exist today. This is why I like the trackless tram: it has the high quality of autonomous transport like light rail, but at a tenth of the cost.

Trackless trams give us the capacity to not only catch up on years of under-investment in transport infrastructure, but also fund ambitious urban regeneration projects that will shape our future cities. This is what is driving trackless tram studies in Townsville, Sydney’s inner west, Wyndham in Melbourne and Perth.

It’s also possible to use trackless trams to create new opportunities on the edges of our cities, like the Western Sydney Aerotropolis. There, Liverpool City Council wants to maximise the benefits of the new airport through transport connectivity back to the city’s CBD. Dr Tim Williams, Australasia cities leader at ARUP, declared Liverpool to be the surprise star of Australia’s future city planning for this reason.

Liverpool’s CBD is less than 18km away from the new airport site now under construction, but it might as well be a world away given the narrow roads and rural lands that currently separate the two.

NSW Opposition Leader Michael Daley has committed A$10 million towards preliminary work on a rapid transit link between the airport and Liverpool should he become premier after the March 23 election.

And Liverpool Council is investing significant resources to find out what these upgrades should be. This is an opportunity to embrace autonomous vehicles like trackless trams to create a strong link between the new airport and aerotropolis.

Adelaide’s driverless electric shuttle for the Tonsley Innovation District is part of a five-year trial of autonomous vehicle tech. David Mariuz/AAP

The role of city councils

Historically, councils have often been the passive recipients of state and federal investments. But councils like Liverpool are recognising their role in championing infrastructure investment that will support high-quality future growth.

Councils are also identifying that they can control many of the mechanisms, particularly planning controls, that could be useful to minimise value leakage and maximise value capture for the common good.

Developers are telling us that if we can give them up-front certainty on quality and timing of infrastructure and associated land development opportunities, then they can be willing partners in co-funding new transport connections like a trackless tram.

The challenge is to create partnerships with all levels of government, developers and the community, to focus the opportunities from current levels of infrastructure investment and enable bold rather than risk-averse approaches to the future.

New technology brings new challenges, but also new opportunities. For the sake of future generations, we need to get in before the window closes.

This article first appeared on The Conversation