Process makes perfect: TAKT | Studio for architecture

Process makes perfect: TAKT | Studio for architecture

Share

This article originally appeared in MEZZANINE issue 5 – available now through newsstands and digitally through Zinio.

The new faces of regional architecture, Brent Dunn and Katharina Hendel of Takt, take us beyond the image – to a place where we can re-engage with the process of collectively creating a dream.

There is no question, the landscape of architectural practice has shifted. The rise of design in popular culture through print and film over the last few years has led to an increased awareness and desire for the architectural archetype from all walks of Australian life, undoubtedly a positive development. But the question remains – how do clients and architects find common ground?

It is a great joy that a lot of new clients in residential architecture come from increasingly diverse backgrounds. With this invigoration of interest, we are pushed to see our role anew, to fan the flames of our clients’ desire to achieve something special in the built form that is unique to them. The first spark is often accompanied by questions and doubt, and layers of previous experiences from ourselves and our clients. The skill is being able to go beyond that, building confidence and reassuring clients that, within the specified parameters, there can be a beautiful, achievable solution.

For most of us, exposure to architecture and design is through shiny, crystal-clear images of successful, often high-end projects, without an understanding of how the client’s needs were met, or the context. Client briefs often include imagery of loved buildings or spaces, but most are solutions to different problems with different constraints. Clearly, these are useful starting points in getting to know each other, though the real power is opening a line of conversation. Investigation into thoughts behind those glossy images – the memories that they evoke, the experiences they recall – is critical.

Understanding the emotional timbre our clients desire requires looking beyond first impressions and opening up to the nuances of dark and light, warmth and cold, rhythm, seasons and place. We invite

our clients to play music for us, show us art, share poems, jokes and stories. Once the discussion moves away from images and towards experiences, the true process begins.

As with any creative profession, there is a temptation to present the client with an equally perfect, shiny solution – a response appropriate for the aesthetic problem-solvers we may see ourselves as being. In doing so, we leave out the importance of architectural process that makes a solution understandable and relatable, the process that makes a building a home, and gives the owners something to talk about in the years to come. Ignoring the process in the ‘process’ also deprives both client and architect of the joy a shared journey can bring – in discovery, in exploration, in finding what makes a project tick.

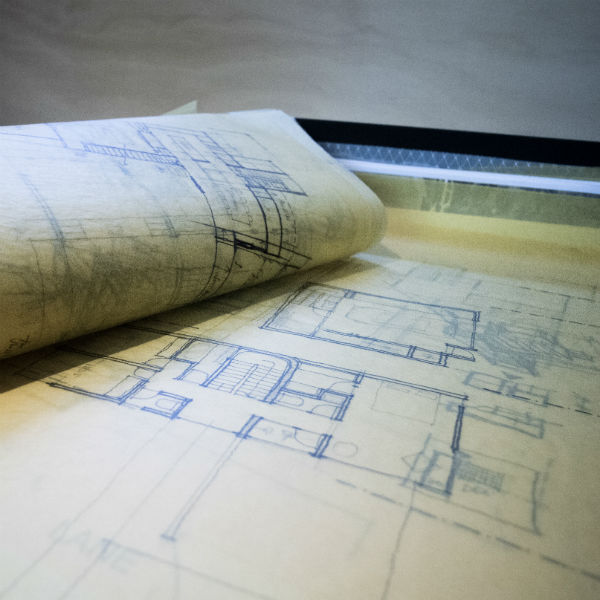

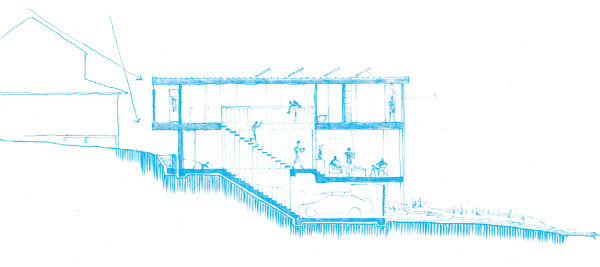

Opening up the initial design discussions and inviting a client to take part is our way of demonstrating what architects do, and the inclusive nature of this approach is a powerful way of engaging our clients. We find ourselves layering ideas on trace, smudging, pointing, discussing, using sketches as a method of summarising. Sometimes this process serves to show that more explanation is required. Or a simple model, physical or digital, may allow a person to engage with their own future dreaming, demonstrating ideas in a visual and visceral way.

This approach peels back the layers of materiality, objects and finishes within a brief to focus on purpose, flow, function, and the relationship between spaces and their immediate surroundings. It gives our clients, those who will live in our homes, a greater understanding of the value we bring to their future lives.

Increasingly, we find ourselves also sharing the missteps and failures, the dead ends and flights of fancy, even taking clients on the design journey with us in design-jam sessions that tighten the feedback loop and allow insight into the many considerations influencing an outcome.

At the end of the day, sharing the design process, as opposed to just the solution, can lead to a better mutual understanding – an understanding of the importance of the bigger picture, of guiding principles, of origins and desires, of the nature of place, and how these help shape the finished project.

This article originally appeared in MEZZANINE issue 5 – available now through newsstands and digitally through Zinio.

You Might also Like