Bronwyn McColl on collaborating with Country in design

Bronwyn McColl on collaborating with Country in design

Share

The Woods Bagot principal, who recently appeared on the ‘Co-designing with Country’ panel at the Melbourne Design Show, advocates for a process of learning and unlearning as we meaningfully co-design with Country.

Hailing from the Sunshine Coast and a family without any background in design, Bronywn McColl has always possessed a passion for creativity and helping people. But she was always unsure how to channel this drive into a career pathway.

After enrolling in design and eventually architecture, the answer became clear for McColl.

“I realised I could make the world a better place through design,” she says.

She started in the small practice and private sector, working on houses and boutique hotels, and was then poached to work for Woods Bagot as an interior designer. McColl led the Brisbane studio for many years, and has now tallied five years in the Melbourne studio.

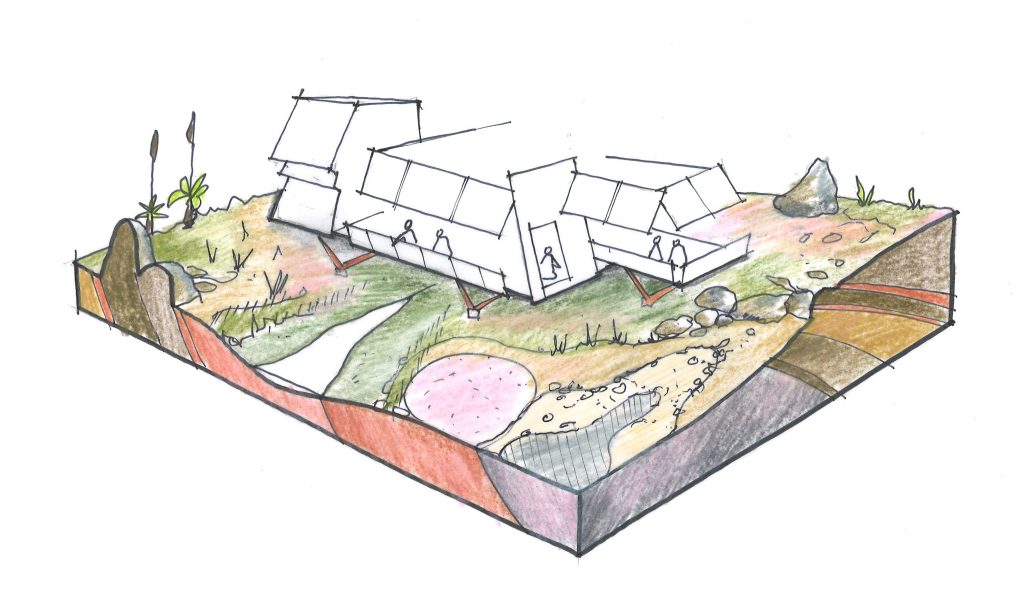

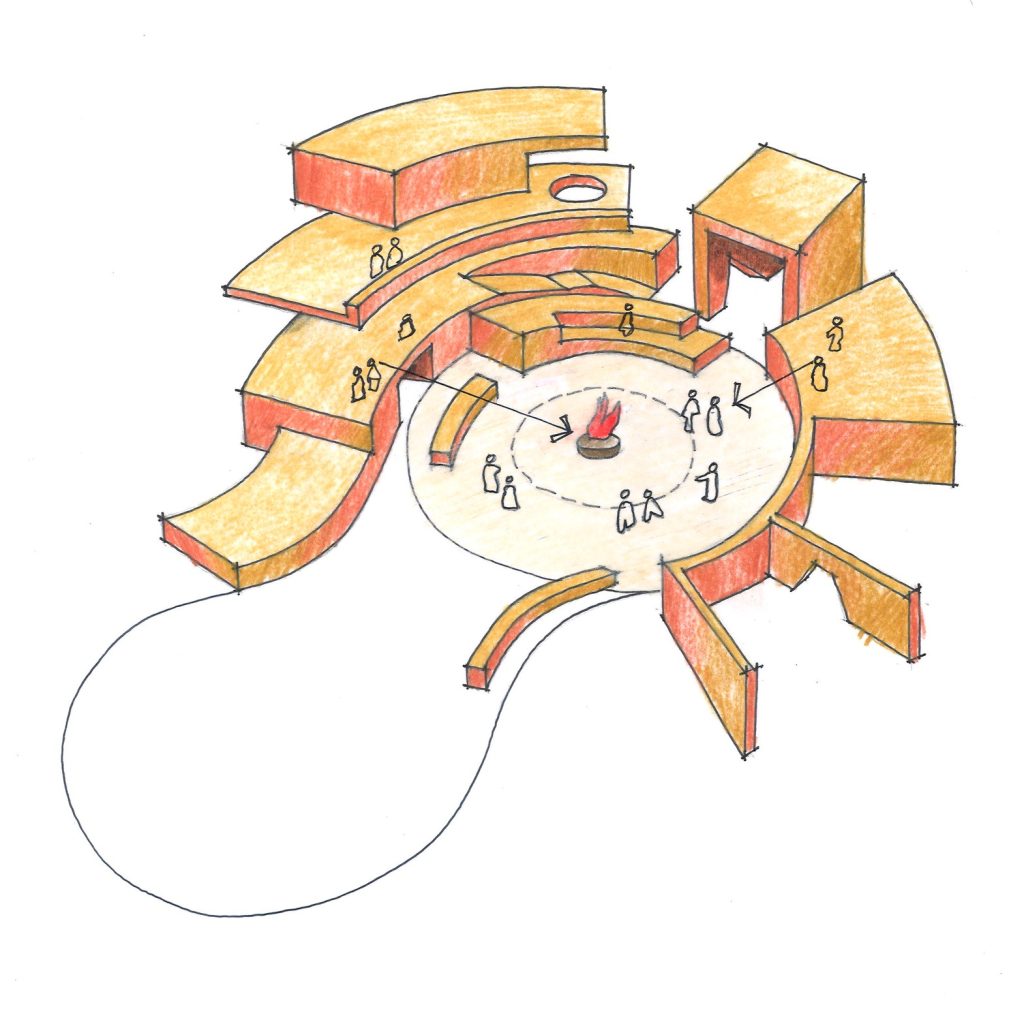

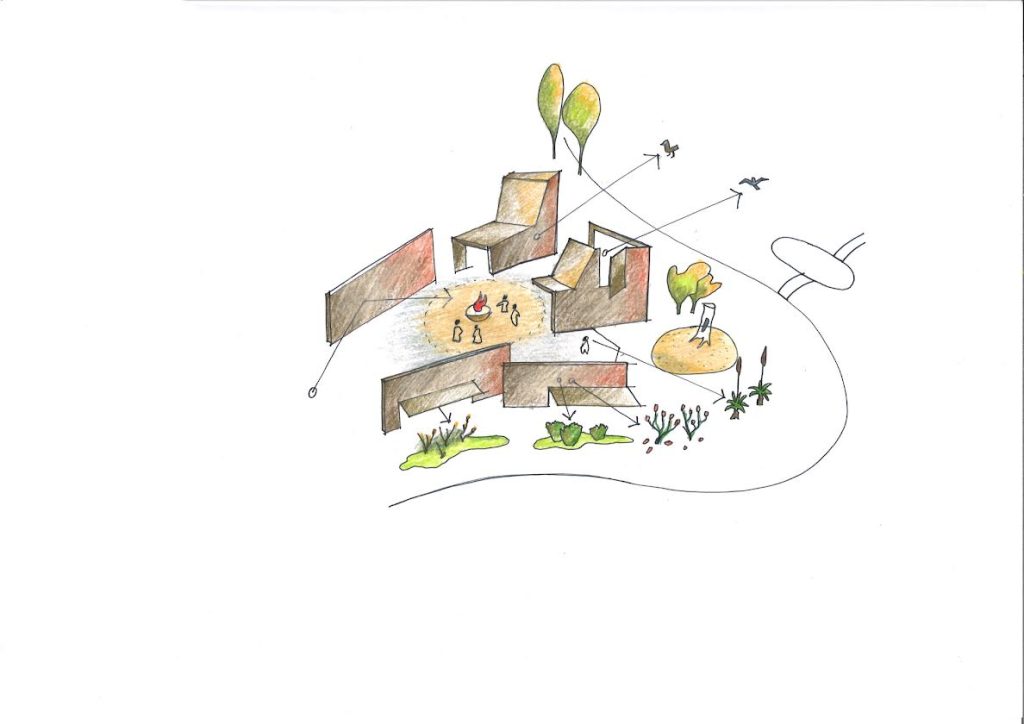

Last February, Woods Bagot was announced as the architects tasked with reimagining the Wathaurong Aboriginal Co-operative in North Geelong, Victoria. The revamp, grounded in concepts of co-development with country, aims to provide holistic wellness services, and gathering, office and event spaces that honour the Wathaurong community.

McColl is fascinated by how different sectors of design – whether it be retail, residential or hospitality – intersect with each other.

“There’s not one sector I haven’t worked in. No matter what sector you are designing for, it’s about how we can impact the world we are creating through design,” she says.

Her staunch allyship towards a wide range of communities reflects her values-and-purpose-driven approach to interior design and architecture.

Inclusive design is a tenet of McColl’s methodology, and she will imminently embark on a PhD regarding care in the built environment. She aims to use design as a vessel in which to amplify frequently silenced and neglected voices.

“It’s not about representing one particular type of person – yet more so someone who usually and historically isn’t at the design table, such as a woman’s voice, a cultural voice, or another disadvantaged voice,” she says.

McColl’s desire to meaningfully engage with First Nations people through design always existed as an “underlying thread”, yet this desire became louder and more apparent after she realised the immense responsibility she holds as a Woods Bagot principal.

“I’ve got a voice and a platform in this space, and I’ve been fortunate to work on projects that enlisted the support of traditional custodians of the land,” she says.

McColl speaks of the exciting turning point in the Australian design landscape. There is an eagerness, although occasionally fused with apprehension, to embrace the permanent rewards of co-designing with Country.

She compares this apprehension about co-designing with Country to how people perceived the role of sustainable design twenty years ago, where understandings were still inchoate and clunky and mistakes were commonplace.

But sustainable design is now intuitive for many architects and designers, and McColl suggests collaborating with Country will eventually become second-nature.

“We now wouldn’t think of designing without sustainability – and that’s how it should be for co-designing with Country… It’s not a question of ‘if’ we do it, but how far we can innovate and push boundaries,” she says.

McColl’s true passion in this learning and unlearning process is helping designers navigate this aforementioned apprehension to engage with First Nations communities. Many designers believe they don’t have the authority to collaborate with Country, or are fearful to speak and act on behalf of communities.

“As an ally, you consider what space and responsibilities you have, and how you can bridge the tricky conversations to ensure you are making the right connections,” she says.

McColl was elated to be involved in the recent designing of the Collingwood Yards-located workspace for the Ilbijerri theatre company, a not-for-profit organisation and the longest established First Nations theatre company in Australia.

Forging connections and rapport with the clients was difficult as the project fell during the COVID-19 lockdowns. But since the workspace launched, a heartwarming support network has emerged.

McColl and her team thoroughly enjoyed unpacking the hopes and intentions of the theatre company, and why they made the move to the Yards space.

The budget was tight, but the team used clever and strategic design to remain within financial parameters and honour the company’s eco-conscious values. The furniture was donated and the team employed Wurundjeri locals to weave woven covers for lampshades.

The participation of traditional custodians in the Ilbijerri project raises an important question – how do designers alleviate the cultural load placed on First Nations people when relying on them to share knowledge that can elevate their designs?

“We’re motivated to have these conversations with First Nations communities and discover how their knowledge can be used in the built environment, but it’s a massive load for people who have already had such a difficult path,” says McColl.

“We shouldn’t be putting this onto communities, but then we shouldn’t be ignoring them.”

McColl addresses a valid consideration currently occupying the design landscape, and every other landscape. She emphasises that the onus falls on non-Indigenous people to alleviate this cultural load by engaging in both independent and assisted learning – accepting that making mistakes and welcoming corrections is part of the journey.

To avoid co-designing with Country lapsing into tokenism and virtue signalling, McColl says determining intent and purpose is imperative.

“What are you hoping to gain from this engagement, from a First Nations and Western perspective? Are you hoping to acquire knowledge regarding sustainability, history or housing?” she questions.

McColl advocates for designers to look inward to identify the desired outcomes of co-designing with Country, and therefore eliminate instances of engaging with First Nations communities to bolster a company’s image, or for self-aggrandising purposes and doing it because you “think you have to”.

McColl highlights that co-designing with Country and learning the memory of a place, involves anyone and everyone who values equal and fair representation and the freedom to exercise cultural expression.

“We need everyone to be a part of this journey. We’re not going to produce anywhere near the volume of things possible if we rely on First Nations people to do things on their own,” she continues.

McColl emphasises the inarguable necessity of employing traditional custodians and Elders as participants for the entire duration of a design project, not just consultants at the start of the process.

She references the goal of Co-chair of the Aboriginal Studies and Indigenous Strategies Committee at La Trobe University Uncle Shane Charles as guiding inspiration. Uncle Shane Charles envisages a hopefully not-too-distant future where all Australians are proud of First Nations history.

Although the learning and relearning process will be different depending on local or global geographic location, Australia can derive inspiration from the steadfast celebration of First Nations culture in New Zealand and Canada, says McColl.

Overall, the Woods Bagot principal is thrilled that the design world is having deeper conversations, and not just to tick the diversity box, but to embrace this amazing opportunity to use design as a vessel in which to celebrate one of the world’s oldest living cultures.

“If I just sit back and think I’m not educated enough, or I may offend someone, then I’ll get to the end of my career and see that there’s a massive opportunity that I didn’t engage with – for me, that’s something that I don’t want to reflect on,” she says.

Photography by Woods Bagot.

Read about Ngen’giwumirri artist Kieren Karritpul co-designing homewares with Country Road.