The Lost City of Melbourne captures a rich architectural history before its demolition

The Lost City of Melbourne captures a rich architectural history before its demolition

Share

A new documentary called The Lost City of Melbourne charts a destructive period in Melbourne’s architectural history when much of its Victorian-era heritage was demolished.

Melbourne was the fastest growing city in the world in the 1850s due in large part to the Gold Rush, becoming more like the bustling cosmopolitan cultural centre it is now.

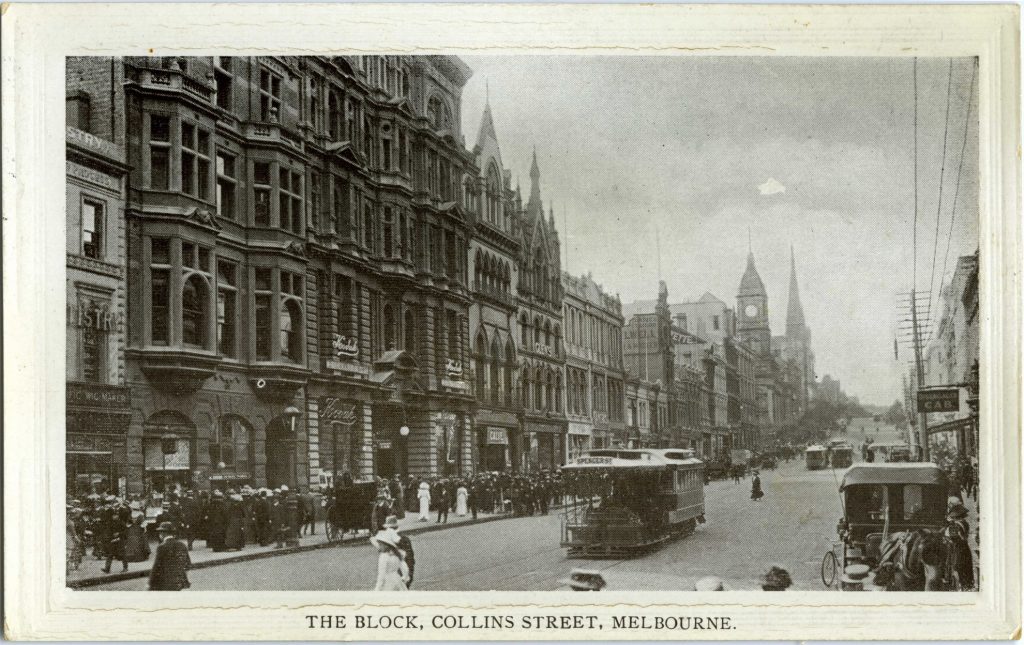

People would get dressed up in their Sunday best just to ‘Do the Block’ of Collins Street, walking past the expensive boutiques or down to the theatre district on Bourke Street.

Decorated with master craftsmanship, the city’s grand Victorian-era hotels, theatres, cafes and markets reflected the way of life for the well-to-do, as well as the sheer amount of money the local government spent on development.

It was also a reflection of colonialism, with this new city built on the land of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung and Bunurong Boon Wurrung peoples, destroying sites of cultural significance to reach that point.

A hundred years later, in the 1950s, the perfect storm of events came together to topple the architecture once again.

Television was invented in 1956, and the world’s eyes were on Melbourne for the Olympic games.

With seemingly much to celebrate, Melbournians were instead suffering cultural cringe. They wanted their city to appear modern like the ones they saw on screens, but felt its colonial architecture did not reflect this.

In an attempt to ‘modernise’ the city, many of its old buildings were demolished from 1956 until the early 1970s.

Walking through the CBD now, few Melbournians realise that high rises stand where the Menzies Hotel or the Eastern Market were only 50 or so years ago. It’s unheard of that such buildings could be destroyed under the Heritage legislation in place now.

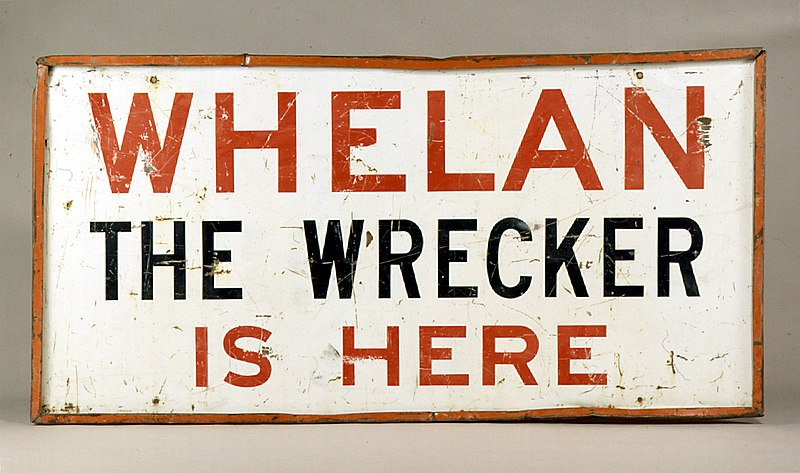

But The Lost City of Melbourne captures a time before the Heritage movement, when the demolition company Whelan the Wrecker had licence to flatten a good portion of the city. Signs declaring ‘Whelan the Wrecker is here’ were such a common sight, the business became a household name.

“I remember in the ‘80s Melbourne was littered with ‘Whelan the Wrecker’ signs,” the film’s director Gus Berger tells Australian Design Review.

“So they definitely were kind of like a villain in my mind growing up in Melbourne because of that relationship with demolition.”

As a filmmaker and owner of the Thornbury Picture House, Berger originally wanted to tell the story of Melbourne’s lost cinemas when he set out to make a documentary over lockdown.

From Hoyt’s Cinema Richmond, to the Plaza Theatre in Northcote or Barkly Theatre in Footscray, many of these old buildings have been demolished, left in disuse or redeveloped into apartments and shops. Berger has always seen this as a great loss.

“I think what made them special was the motivation on behalf of the architects to create a space that would mirror the experience that people are going to have when they go inside these places. So you’re creating a kind of like an artificial, dream-like, escapism experience for people,” he says.

“And to experience that in this grand, big, beautiful building with high ceilings and ornate features and plasterwork and leather seats, you’re just transporting people into another world for two or three hours.”

In his research, Berger soon found out that Melbourne demolished much more than its cinemas over that short period this past century.

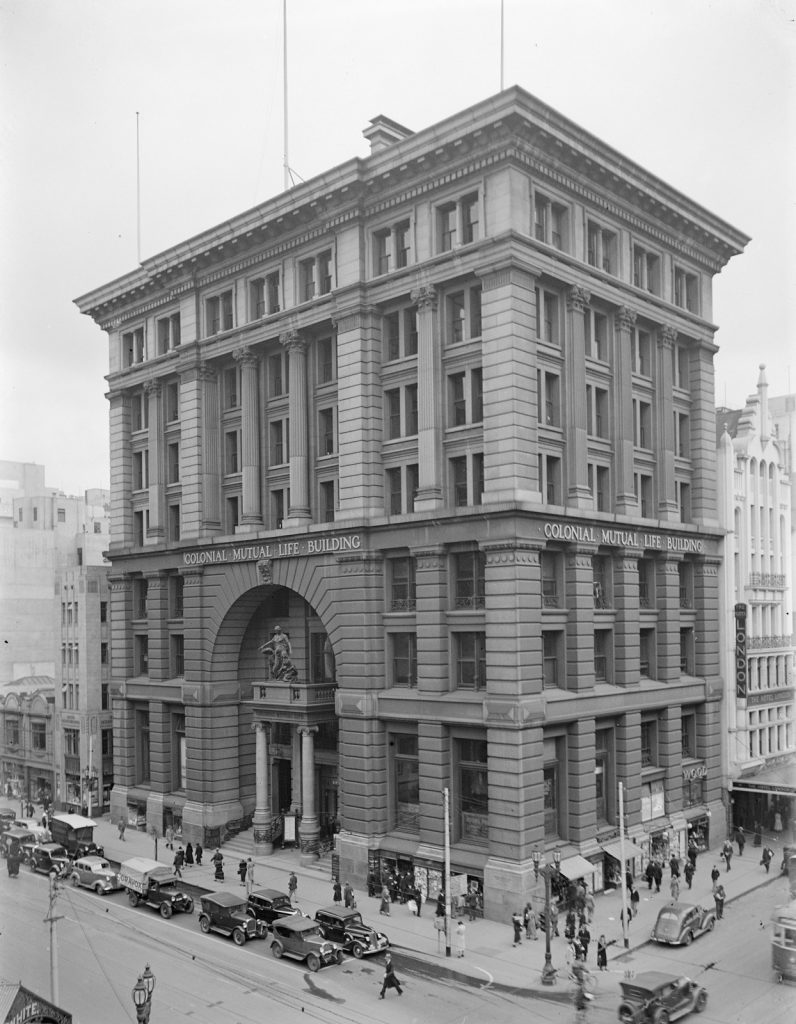

Built to be the “grandest building in the Southern Hemisphere”, The Colonial Mutual Life building on the corner of Elizabeth and Collins streets was one of the major losses in 1960.

Whelan The Wrecker, despite committing the act, was actually among the few that recognised the value in what it knocked down and kept the artefacts. Parts of the Colonial Mutual can now be found at the University of Melbourne or the Melbourne Museum.

“I mean, it’s good that we can go to that park at Melbourne Uni and we can see this beautiful statue that used to adorn the entrance to an incredible building like Colonial Mutual building that was built to last three World Wars and outlive the pyramids,” Berger laughs.

“I would rather it still be there, but it’s better than not having any remnants left of it at all.”

The line in the sand of this unfettered demolition period was the potential destruction of the Regent Theatre on Collins Street in the 1960s.

“When we did almost lose the Regent, that was the first time when people realised that they could actually have a say in what was happening to the built heritage,” says Berger.

“I think that was a really important turning point. And then from there, we managed to get legislation to stop further destruction of some of our beautiful old buildings.”

While not all have survived demolition since the introduction of Heritage legislation, Melbourne still has icons like the Regent, the Astor Theatre and the Forum.

“We actually are very lucky, we haven’t lost everything, we’ve still got a lot of beautiful buildings and grand architecture left in the city,” says Berger.

“Once you appreciate that and value that then you’re a lot more inclined to make sure that we don’t lose it.”

To watch The Lost City of Melbourne, head to the website for screenings.

For more on this issue, Architecture Review asked a panel of experts in 2019 whether Heritage concerns and constraints were still important.

You Might also Like