The physical model is anything but obsolete, says Woods Bagot model maker

The physical model is anything but obsolete, says Woods Bagot model maker

Share

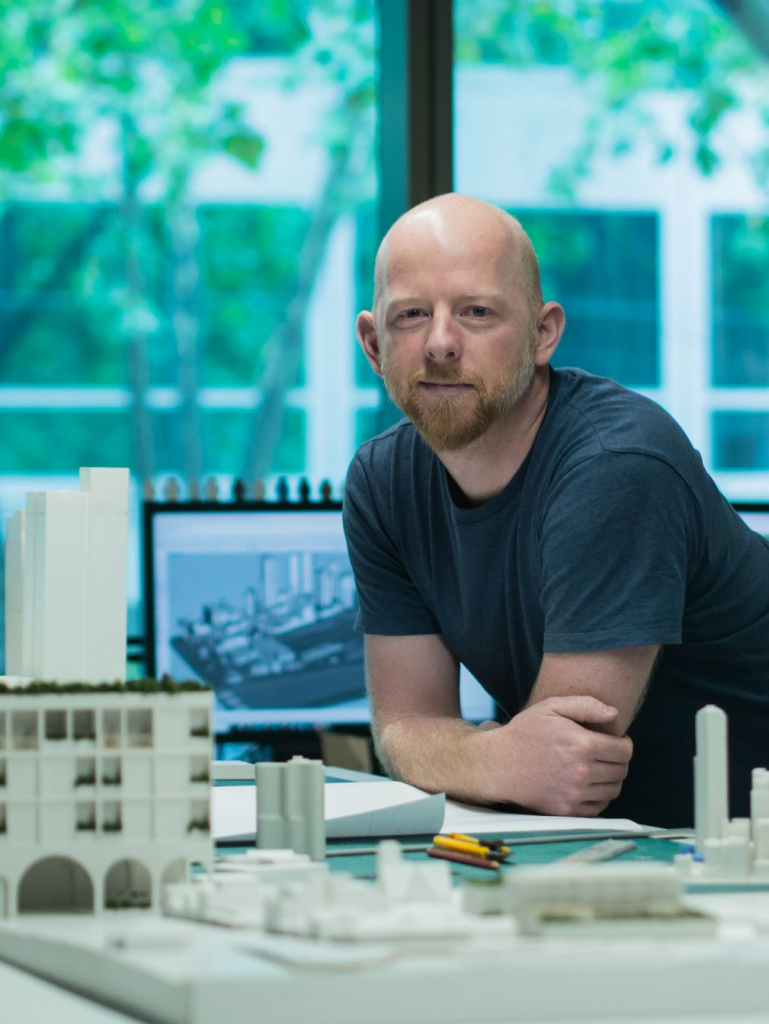

It’s a dying art, but one that John Sargood preserves in a workshop cluttered with perfectly detailed miniatures of Woods Bagot buildings destined to grace skylines the world over.

It’s an almost impossible task to capture John Sargood’s world in print. Reading back over our conversation, it’s quickly apparent that so much is missing. Sargood speaks on his feet, constantly picking up and gesturing to half-completed city squares and unbelievably small terraces.

Moving from one end of his messy workshop to the other, he overwhelms listeners with a stream of consciousness-style monologue about the multitude of projects he’s almost finished, pretty much finished, only just beginning.

He recognises every single building, can reel off its specs in seconds, can point it out in any skyline here or overseas. His memory is mechanical, but his craft is ancient.

Model makers have been a feature of architecture since prehistory. The oldest known models are of the Tarxien Temples in Malta, now on display in the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta.

In the 18th century, cork models were sought after by kings and princes and collected by the British Museum and architects like Louis-François Cassas.

They were an essential part of an architect or designer’s daily life, a necessary tool to study the interaction of volumes, different viewpoints and concepts during the design process. Then someone invented three-dimensional (3D) rendering.

“The model in the architectural studio is about an exploration. It’s akin to the construction site. You’re starting to create this thing, building it, testing it, being able to subtract for it and so the process is more open,” explains Sargood.

“The model is not the finished product that you put on your shelf at the end. The model is a really important part of getting to where you’re going. It’s much easier to make a really nice clean thing on the computer. You can draw beautiful lines and it all works, but you have no idea about scale, about material and all those other things until you actually make one.”

For Sargood, this realisation manifested long before he stepped into Woods Bagot’s Melbourne office.

The model maker has a background in product design and a childhood defined by “forever pulling things apart and putting them back together,” he says.

“I remember making a design for a helmet. I’d spent a couple of weeks drawing things in a sketchbook. I filled up 20 pages. Then I’d go to the computer and try to model this thing. I just couldn’t get it working. I thought, ‘I’m just going to make one.’ I got a cheap helmet, covered it in foam and hacked it with a knife. Within about an hour, I had a thing that looked exactly like I wanted. It was an ‘I see’ moment. You make one, it fits, it works and that’s the basis.”

Woods Bagot is in a position where it can engage a full-time model maker on-site, a luxury most practices can’t afford.

Sargood makes a model for every Woods Bagot project, coming into the process as early as two weeks from commission and often making two or three versions of the same design. In those early stages of design, the architect hasn’t worked out every detail and Sargood frequently has to fill in the gaps.

“I’m not a structural engineer, so I don’t know if things will actually fall over, but I can say, ‘You need to make sure you know what’s going on with this wall and that wall, or does this stair go right up to the floor? Is there one more step?’ Little details that are very important to me because I need to be able to make things that actually fit together.”

Sargood will make small additions or subtractions to the architect’s design, adding details that have either been overlooked or left out due to time constraints. Sometimes, though, the finished model just isn’t what everyone was imagining.

“The first few times that happens, that can feel personal. You can feel like you’ve done that wrong. But it’s the model that has given them an instant understanding of what’s wrong. Even though it’s taken me a day and a half to build it and it’s taken them 10 seconds to say they didn’t like it, it’s a point of pride for me that design decisions are taken on the back of all these models.”

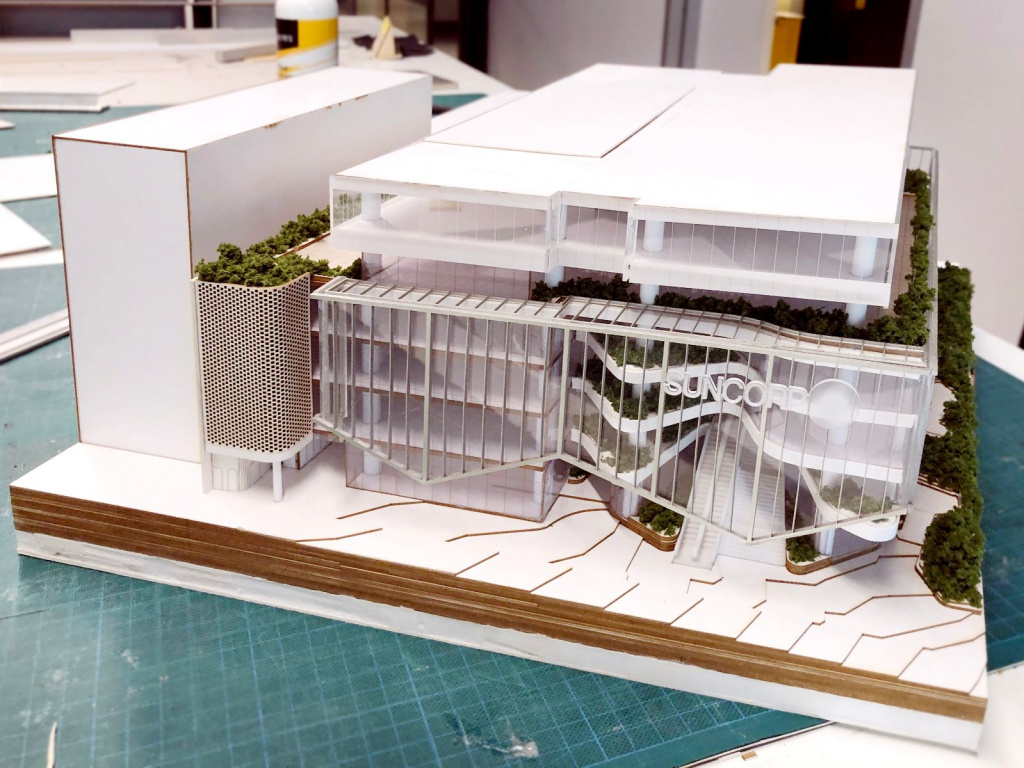

Sargood keeps the Woods Bagot models abstract, using a laser cutter and 3D printer to shape wood, plastic, clear acrylic sheets and cardboard to recreate the architect’s design. His models are to scale, a process that took some time to master.

“I remember, early on, making buildings that were literally twice as large as they should be or maybe even 10 times as large because I left off a zero.”

Elements that are too small or too fine to print, are made by hand; paints and other materials are added to mimic concrete or steel. The last half an hour of work is usually adding greenery and, surprisingly, toy cars.

“Occasionally I find myself sitting here building little houses and sticking them on. Then I get a bit of self-perspective, thinking, ‘I’m about to put this house on a little landscape that I’ve built that goes next to that other house, and I’ve been there, I know what it looks like. This is a job. This is great’.”

The tiny, if somewhat unnecessary, details are part of what Sargood describes as instantly recognisable pieces of scale that people can “easily attach themselves to”. The cars and bushes help designers and clients better imagine the scope of the project and its position in the landscape.

“It gives them a sense of comfort. It’s that tangibility you get out of a model – that it is very much a self-communicator versus that render, which can sometimes be a bit misleading,” he says.

A computer render is about the atmosphere. The model is about construction, buildability and the physical.

A lot of what Sargood does is already 3D print and paste or mocked up entirely on the computer, but a handmade model, like his favourite, the Woods Bagot Victoria Police Centre on Melbourne’s Spencer Street, continues to enchant, if only from a purely cosmetic perspective.

“I think there will always be a place for models in architecture, even if it’s just for that moment at the end of the meeting when you’ve displayed all of your renders, done all of your 3D modelling and then you lift the sheet off the model and go look at what the client has bought.

“That’s worth something, that moment of excitement, because if you’re not excited about it, you shouldn’t be building it. If we can keep the architect excited, we can keep the clients excited and we can make sure we end up with better buildings.”

Photography: Woods Bagot

Woods Bagot has recently been designing responses to COVID-19, releasing office layouts for workplaces post-coronavirus and adaptable apartments for WFH.