NGV unveils program for Triennial 2020

NGV unveils program for Triennial 2020

Share

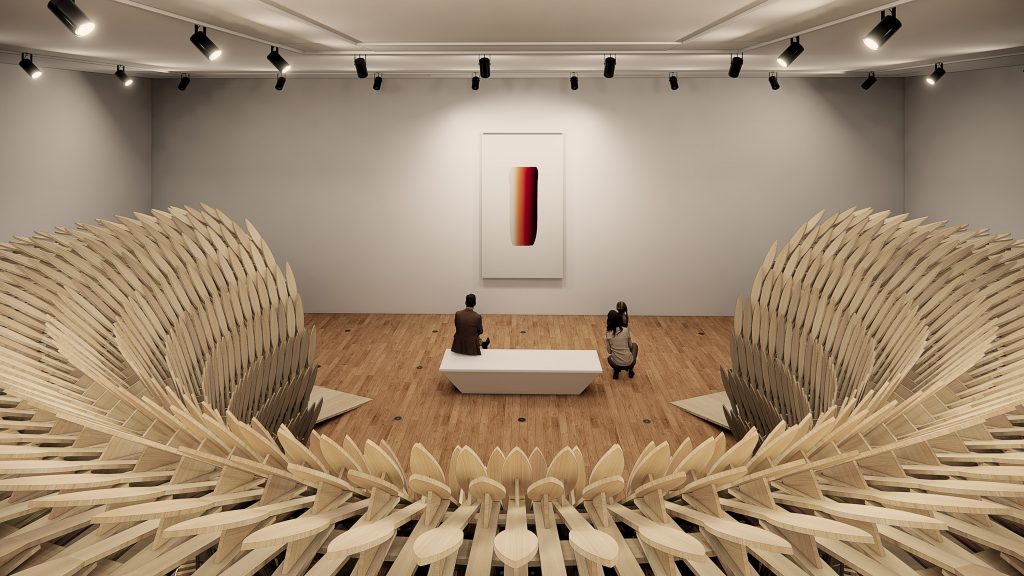

Works from Kengo Kuma will be among the 86 projects on display at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) when its Triennial opens later this year.

While COVID-19 restrictions have led to the postponement or cancellation of many exhibitions globally, the Melbourne gallery has decided to go ahead with its Triennal, which will feature more than 100 artists, designers and collectives from more than 30 countries.

Each has been commissioned to produce a new work especially for the large-scale exhibition of international contemporary art, design and architecture, which opens on 19 December.

This is the second time the NGV has organised a Triennial. Visitors will be able to explore the entire exhibition in person for free until it closes on 18 April 2021.

Speaking to ADR, senior curator of the NGV Department of Contemporary Design and Architecture Ewan McEoin described the event as a “microcosm of the world today.

“Unlike many triennials and biennials, it’s not created around a central theme. It’s more of a snapshot of practice,” he explains.

“(In this edition), we’re seeing very strong messages around climate change, as well as identity politics and racial issues, but also the emergence of artificial intelligence and how technology will shape the future of our lives for the better or possibly worse.”

A number of these themes are explored in Kuma’s collaboration with Geoffrey Nees. The Japanese architect and Melbourne artist have created a pavilion from timber harvested from trees that died during the Millennium Drought at Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens, some of which pre-date European colonisation.

Prioritising natural phenomena over scientific order, the botanical species used are colour coded rather than following any taxonomic order in a statement by the designers against the reductive nature of science during the colonial era – a mindset at odds with many Indigenous cultural beliefs and knowledge systems.

Similar themes will be explored elsewhere in 15 large-scale bark paintings and nine larrakitj (hollow poles) by Yolngu woman Dhambit Mununggurr, the first Yolngu artist to depict country in her signature shades of acrylic blue paint.

The Triennial will take over the entire NGV International Building, designed by Sir Roy Grounds in 1968 and home to a “very fulsome historical collection” of decorative arts, paintings and sculptures.

As a result, McEoin says a lot of the projects respond to their setting.

“They engage in a conversation between the (NGV’s) historical collection and the works because, of course, the historical collection talks about history and the history of race and identity and environment,” he explains.

“(The juxtaposition) gives us sense of where we have come from through to where we are now, and also looks back at the collection and asks, ‘What do we think of those histories and how do we reevaluate?’.”

It’s a topic Edition Office and Kokatha and Nukunu artist Yhonnie Scarce also explored in last year’s NGV Architectural Commission.

Another highlight from the upcoming Triennial is Tel Aviv-based designer Erez Nevi Pana’s salt architecture.

Pana has been commissioned to produce the world first, which consists of four distinct structural elements – a ladder, boulder, steps and walkway, made entirely from salt and assembled into one exploratory architectural work that aims to represent the journey from water to land.

The Michael and Janet Buxton Foundation and MAB Corporation Pty Ltd, 2020 © Erez Nevi Pana. Photo: Dor Kedmi.

“A lot of projects are not artworks,” says McEwoin. “They are investigations into thinking that will change the way the mainstream design industry will work eventually.”

“This is research that then informs behaviour change where larger manufacturing companies or designers or specifiers have to think more about where materials come from, for example, and the political, social and ecological problems they create.”

To celebrate the NGV Triennial, ADR will be chatting to some of the featured designers, including Pana, over the coming weeks.

The free exhibition will run from 19 December 2020 to 18 April 2021. To find out more, visit the NGV website.

Lead photo: Sibling Architecture, which has also produced work for the Triennial. Photo: Christine Francis

You Might also Like