Do joint ventures hold the key to large-scale project success?

Do joint ventures hold the key to large-scale project success?

Share

In an increasingly globalised architecture and construction market, the number of large-scale projects being delivered as joint ventures and under JV contractual agreements is growing, but with increased size and complexity comes additional risks and new challenges. Is your firm ready to compete?

In the past, Australian architecture joint ventures (JVs) have typically involved bringing together interstate peers to provide complementary expertise and/or proximity, or practices joining forces to deliver specialised buildings, or collaborations between different-sized firms to enhance capacity and upscale their projects.

But a new trend is emerging: Australian firms are partnering with international practices to deliver large-scale projects.

This trend is driven largely by clients, especially state government clients that stipulate the use of international firms in design competitions, such as the WA Museum project (currently in construction, by HASSELL + OMA), the Adelaide Contemporary International Design Competition (won by Diller Scofidio and Renfro and Woods Bagot, currently shelved) and the Sydney Fish Market (won by 3XN with BVN and Aspect Studios). Another good example is the current relocation of the Powerhouse Museum to Parramatta project. The first stage of its international design competition for the new museum attracted 74 submissions from 20 countries, made up by more than 500 individual firms from five continents. Six teams have been shortlisted with a winning design for the new museum to be announced in late 2019.

Such client demands leave Australian firms little option but to form JVs to compete, but not all firms are happy about this trend.

“The question about JVs with overseas architects – which has become a big issue with projects in Melbourne, and Australia generally – is that a lot of international firms are looking for new markets, and they are quite opportunistic around public buildings and large projects,” says Peter Bickle, principal at ARM.

“This is a conversation that is currently ongoing within the profession,” he says. “Some see the situation to their advantage, while others think: ‘Why can’t we do the project?’”

Regardless of where you sit on the subject of international JVs, there are several key issues to consider before undertaking both local and overseas partnerships.

Pedram Danesh-Mand, director of Project Risk Consulting at KPMG, says the risk of project failure is higher on JVs, with a large portion globally resulting in litigation. He warns that the term joint venture has no settled common law meaning in Australia, meaning such arrangements can take various forms. “They could be undertaken through a partnership or some other form of unincorporated association, or through an incorporated body,” Danesh-Mand explains, adding that it’s important to agree upon a suitable legal framework as well as other – perhaps less obvious – issues.

“In my experience with a number of successful JVs and few challenging ones – from a risk and project controls perspective – there are a number of blind spots that have to be identified and managed proactively,” says Danesh-Mand.

“The key pitfalls include unrealistic deadlines and targets; lack of quantitative risk assessment discipline; unreliable or lack of forecasting mechanisms; inaccurate progress measurement, including lack of change control; unclear RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted and Informed) matrices; and a lack of managing the people dimensions of change.”

Capability alignment

In simple terms, the most important areas of concern fall under the headlines of alignment of capabilities, appropriate risk allocations, culture and communications.

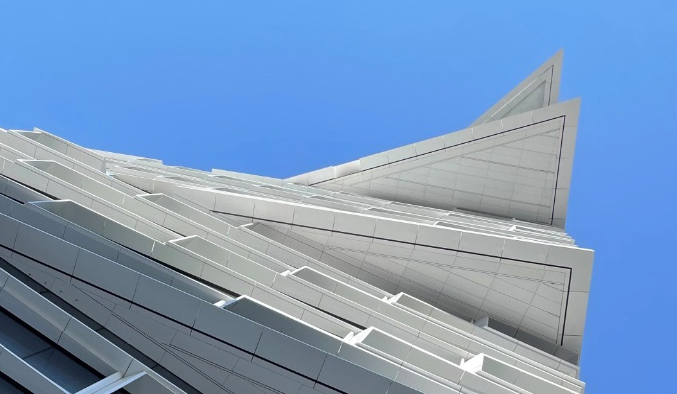

Rhonda Mitchell, a principal at Woods Bagot, is leading the collaboration with New York-based SHoP Architects on Collins Arch, a five-year project due for completion in early 2020. She says it’s important to get the legal and operational framework in place (for the mechanics of the project), but adds that the spirit of the partnership is critical for a successful collaboration, and it requires ongoing commitment and a best-for-project attitude.

“Both firms were accustomed to the challenges of working across time zones, but for this project having the SHoP team based in Melbourne and New York for the duration of the project has been central to maintaining communication and a proactive engaging team environment,” Mitchell says. “The round the clock studio has also proven a productive working model.

“It does take a bit of extra energy and require an additional management overlay, but those investments are worth it to achieve the desired outcome.”

Of course, legal problems can arise on JVs that are beyond the remit of architects, but these still have the potential to impact upon a firm’s brand and reputation. When projects end up in court, parties are usually subject to confidentiality agreements, so the nature of the dispute and the resolution aren’t necessarily understood beyond those closed doors.

Such was the case on the Perth Children’s Hospital project, delivered by a JV comprising JCY Architects and Urban Designers, Cox Architecture and Billard Leece Partnership, with HKS Inc. The project was delayed several times and legal disputes between the client and lead contractor are ongoing, although the architects are no longer involved.

According to a Public Accounts Committee report tabled in the Western Australian Parliament, the initial problems stemmed from the fast-track nature of the project, and were compounded by client changes, the use of non-approved building materials and a poor governance structure.

According to Andrew Rogerson, who was a director at JCY during the project, the architecture JV was successful, and problems associated with the project did not directly force the closure of JCY in 2017. While these issues contributed, he blamed a lack of new projects and the poor economic outlook in West Australia at that time for the practice’s demise.

“From our perspective, joint ventures are a good methodology to bring the correct expertise to a project; JCY used to go into working-in-association arrangements regularly,” he says. “We’d worked with both Cox and Billard Leece Partnership previously, and we knew and trusted those firms and they brought different strengths to the team, which was key to the success of the project.”

Mitigating disputes

This case illustrates the important role of procurement processes, contractual arrangements and governance structures, all of which are critical to the success or failure of a JV.

Danesh-Mand says the most effective way to mitigate the likelihood of disagreements and disputes is not via complicated legally drafted agreements, but to clearly understand, assess, quantify, allocate and communicate the risks – appropriately and reasonably – from the outset.

“JV partners must find ways to balance the pressure on deadlines and targets with the demands of establishing a healthy JV – especially spending their time and resources in line with the potential key risks, for value and impact,” he adds. “No single approach will work for every company or in all circumstances, but if sharing the risks under uncertain circumstances is one of the objectives for executing a JV, it is intuitive that the most time should be spent to assess – preferably quantitatively – and allocate risks appropriately.”

Danesh-Mand says there is considerable scope for improvement in this area and points to KPMG Australia’s recent survey of construction and engineering firms, which found that only three percent of participating organisations were adequately investing in project governance, technology and people.

“Innovative leaders are significantly ahead when it comes to technology, governance and integrated project controls, and project management reporting systems,” he asserts. “Our survey indicated that less than 10 percent of Australian organisations have implemented the appropriate systems and platforms for delivering and controlling major projects, while 85 percent of ‘behind the curve’ organisations continue to use multiple spreadsheets or disparate systems, requiring manual reconciliation and updates.”

So what’s the best way for Australian architecture firms to remain competitive and profitable when executing large JV projects?

“Australian organisations face a race to improve their productivity by developing and implementing robust governance, project controls, data-based solutions and new digital technologies,” Danesh-Mand says. “These will enable them to enhance their profitability and improve the ‘fitness’ of their human capital, while selecting and administrating the most suitable type of contract for their circumstances.”

Image: Collins Arch, Woods Bagot and SHoP Architects

This article originally appeared in Architectural Review #162

You Might also Like