Interior architectural designer Ilianna Ginnis on designing for nonverbal communicators

Interior architectural designer Ilianna Ginnis on designing for nonverbal communicators

Share

“In 2021, someone who’s nonverbal still can’t order a coffee independently because design doesn’t facilitate for that,” Ilianna Ginnis tells me recently.

The interior architectural designer, disability advocate and PhD candidate at Monash University is researching how designers can interact with nonverbal communicators to make more inclusive processes.

She says this form of participatory design is still lacking in Australia, often resulting is spaces that are “designed in the absence” of nonverbal communicators and ultimately ineffective.

“Designers and developers are worried that participatory design costs a lot,” she says.

“But by disregarding conditions like dementia and nonverbal or communication disabilities, they’re excluding a lot of people who just aren’t spending time in their spaces because they don’t facilitate their needs.

“If they did, these groups would be more likely to buy food, eat there, buy clothes and spend more time there, so, in that regard, it would make economic sense.”

Born in Greece, Ginnis says her first experiences with sensory architecture was with her sister, Michelle, who had intellectual disabilities and was a non-verbal communicator.

“My sister would tap on the light because she wanted it to work in a certain pattern, and her teacher or the operator would go and switch on the lights. She couldn’t control them herself. She had to rely on a neurotypical adult.

“And I remember thinking, ‘Wow, architecture is really delayed in this area’. Even in their own sensory room, a nonverbal person doesn’t have a voice and their needs and desires still aren’t being met.

“I was 14 at the time and now at 24, I realise these spaces, as inadequate as they were, are becoming rarer. They’re in decline because they’re expensive and limiting. It’s concerning.”

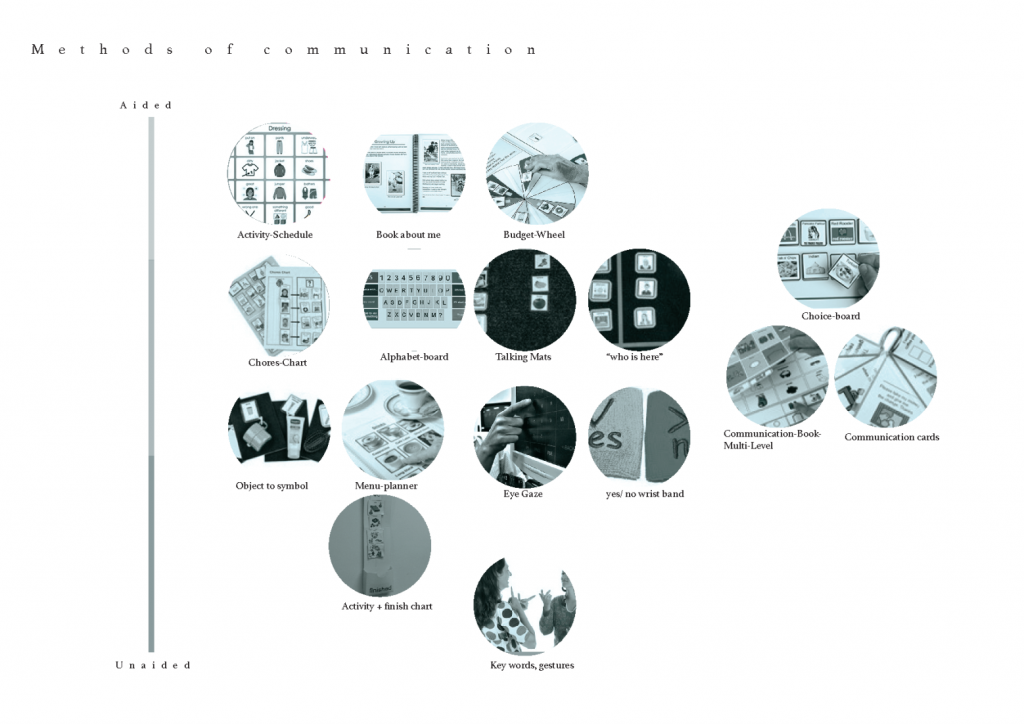

A key area of Ginnis’s research is communication – with the nonverbal participant, their families, carers and teachers.

Nonverbal communicators communicate in different forms; some use gestures, other pictures, while others still might use textures or behavioural means.

The onus is on the designer to “get their hands” dirty, talk to all parties and understand what they need.

Questions like, What are the person’s interests and how can we build around them? Who are their main support? What key considerations do they need for their communication? How can the space respond to these needs?, are essential to participatory design, according to Ginnis.

“If the designer sits with the nonverbal individual, they start to build a bigger picture of this person’s needs,” she says.

“All it takes is to actually observe and understand and have that empathetic and respectful approach to design practice. That’s what’s currently missing.”

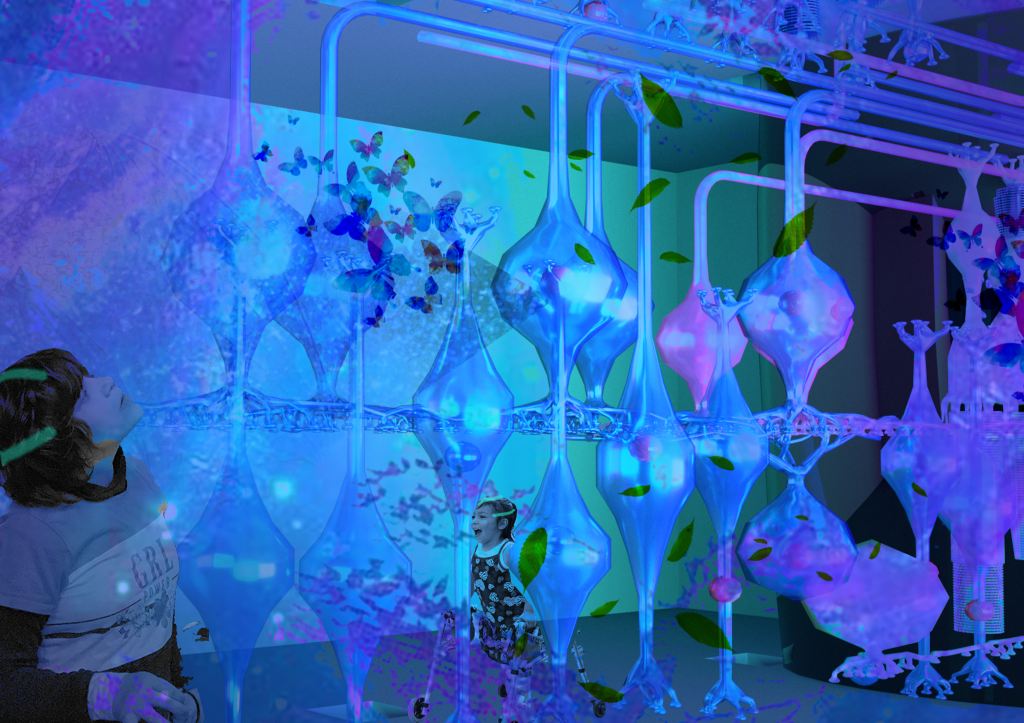

With this in mind, Ginnis recently developed a home for the nonverbal in which she limited her role to that of facilitator.

“It was quite a complicated design process, but the whole house was designed by the five nonverbal participants themselves. I communicated various materials and options – via their preferred means – but they made the decisions.”

The interior architectural designer is set to explore this further at next month’s MPavilion, teaming up with Monash University’s head of industrial design Dr Kanvar Nayer for a workshop on dementia and disability.

During the session, the duo will be inviting designers, occupational therapists and architects to look at nonverbal and dementia profiles and apply an empathetic design approach.

Ginnis says she hopes the event and her research at large will bring about change not just within the industry, but also future design and architectural education.

It’s something she believes is all the more relevant in this new ‘COVID normal’ as technologies like Zoom serve to further exclude nonverbal communicators.

“We live in a neurotypical world where structures and social structures are built on neurotypical forms of communication and comprehension, so that when someone nonverbal enters the room, we don’t know,” she says.

“As designers, we should be modifying buildings to implement nonverbal forms of communication. So that people who are nonverbal will not walk into a building and require immediate assistance, but can rather approach that situation with greater independence and empowerment.

“That’s designing inclusion over designing exclusion.”

Read more about Ilianna Ginnis’s research on her on website.

Melbourne’s MPavilion opens at the Queen Victoria Gardens on 12 November 2021.

Photography, drawing and graphics courtesy of Ilianna Ginnis.

Earlier this year, ADR caught up with Studio Tate’s Carley Nicholls to talk about how not making great design accessible to the wider community is a missed opportunity for Australian architects and designers.