Beyond the Modern house

Beyond the Modern house

Share

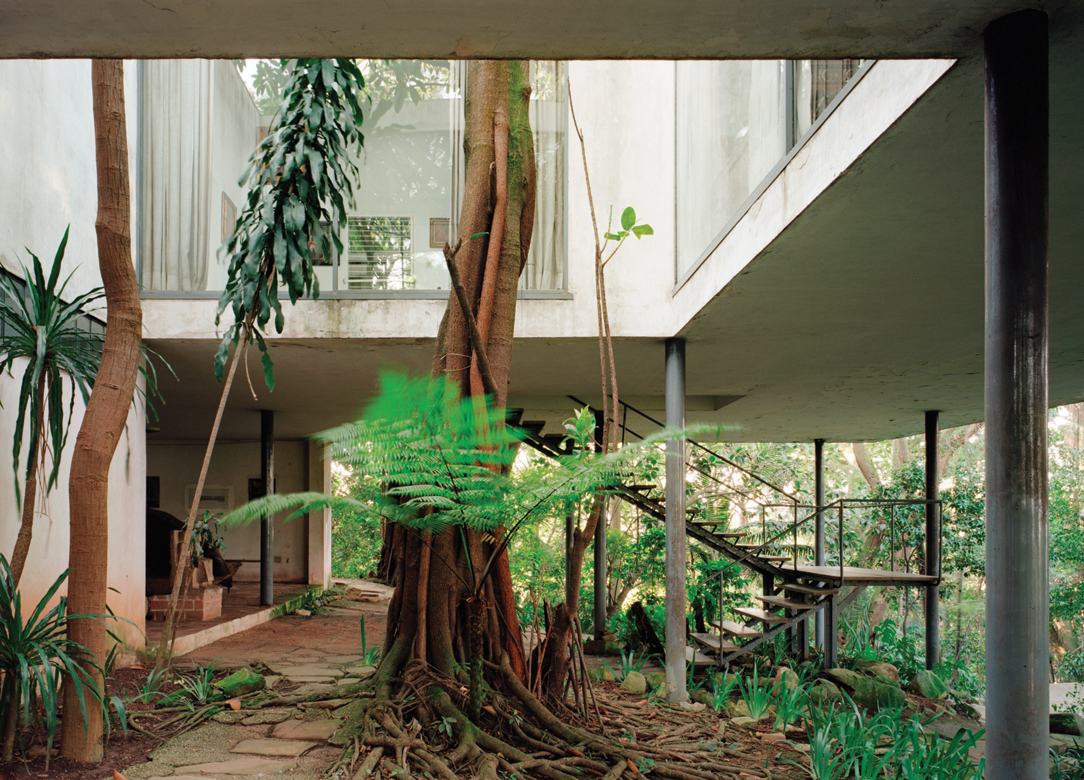

Above image: The interior has lost its resonance but maintains the idea of ‘house as aquarium’. Courtesy Nelson Kon.

Withdrawn from its urban surroundings by an exuberant string of tropical foliage, Lina Bo Bardi’s Casa de Vidro (Glass House) – built in São Paulo for her husband, Pietro Maria Bardi, and herself, in 1951 – still reflects the architect’s cherished idea of a house as an aquarium. Nonetheless, the interior, which for years the Bardis turned into a well-tempered depot of their collecting impulses, has lost its resonance, with the humid depths of the enveloping garden.

Functioning as a foundation for the couple’s intellectual and artistic legacy since 1990, the house has been adapted progressively to comply with contemporary archival needs. In the process of becoming a public research facility, it has lost its genuine charm to make the old and the new coexist harmoniously, such was the mastery of the Bardis. Rearranged to better serve visitors, the pieces of furniture – many designed by the architect – and myriad artistic fi ndings that once enlivened the casa (ranging from a fifth century statue of Diana to a papier mâché head of the Esso Tiger) are strangers to the new context; the house’s interior looks more today like it did when it was built and the Modernist clinical features that informed it prevailed over its domesticity.

Certainly, the couple’s avidity for rarities fostered the premature maturity of the house’s interior. Connatural to their Italian origin, the Bardis’ regard for the past as part of the present followed them to Brazil, where they moved in 1946. Pietro, who had collected all sorts of trinkets from an early age and became over time a renowned art dealer, had often claimed through his writings in Italy the uniqueness of art, that is, the non-distinction between major and minor arts. This philosophy guided his collecting spirit while acquiring pieces for the galleries he administered in Milan and Rome, during the 1920s and 1930s, and would do so while he assembled the collection of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), which he directed from 1947 until shortly before he died in 1999. Lina, for her part, had taken her first professional steps in Milan under the tutelage of Giò Ponti, whose work was well-known for enhancing the conviviality between the traditional and modernity. The mostly interior architectural project commissions she and her partner, Carlo Pagani, designed in the Lombardy capital were unmistakably inspired by Ponti’s designs.

Soon after arriving in Brazil, Lina and Pietro added to their list of collectibles a new pursuit, what they called ‘primitive art’; an instinctive, ingenious and dis-interested popular expression that, in its ethic, poetic and political dimension, fulfilled their ideal of a humanist culture. Gathered in different trips throughout the country, votive offerings, delicate ceramics, religious carvings, rusted tools and elementary artefacts began filling the Casa de Vidro’s nooks.

At the same time, the couple started promoting their notion of primitive art as ‘the true Brazilian art’ in the pages of Habitat magazine (which they founded in São Paulo in 1950) and in the halls of MASP, where they curated several exhibitions around this theme. By claiming that such art embodied Brazil’s cultural essence and that it was ethically exemplary for artistic production, the Bardis aimed at persuading the country’s collective consciousness on how to afford Brazil a competent identity. Despite governmental efforts following the culmination of Getulio Vargas’ tenure (1930–1945) to provide the country with a contemporary appearance, the complexity of foreign cultural dependence and a lingering colonialism continued to hinder national pride.

The Bardis’ claim for ‘primitive art’ as appropriate for representing Brazil with dignity entailed a critique against the alien sophistication of much of the Modern architecture that was built in the country up to that point. Ultimately, their claim was directed against the government’s blind faith that Modern architecture could alleviate Brazil’s feeling of inferiority. The imported features the Bardis wanted to create in Casa de Vidro have slowly dissipated over the years, so much so that the increasingly assorted interior and leafy exterior absolves the link between the house’s construction and Bo Bardi’s initial intent.

The few residential commissions that the architect accepted following the Casa de Vidro reflect her alignment with the critical perspective over the International Style’s social and environmental detachment that emerged from intellectual circles, such as the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM), following World War II. Notwithstanding her refusal to undertake dwelling commissions other than those of close friends, Bo Bardi responded to her interest in social habitats, carrying out numerous housing studies. In these projects, as well as in the only two residences that Bo Bardi completed (excluding her own), she strived to achieve material and cultural integration with their surrounding context. The Valéria Cirell House was completed in 1957, located close to Casa de Vidro, and the Chame Chame House, designed in Salvador de Bahia, 1958.

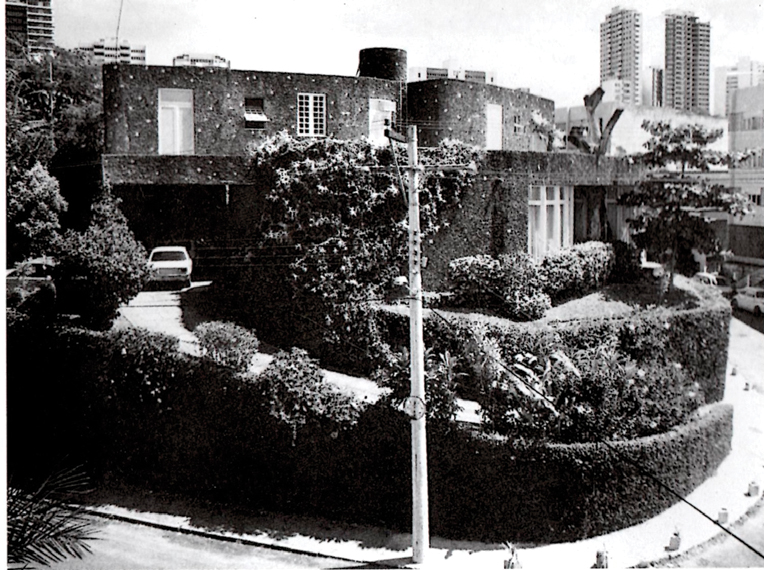

These projects signalled a fresh look upon the Modern constraints with which Bo Bardi approached the residences: form, construction and material. The form, seemingly distilling the principles of the organic architecture advocated by Frank Lloyd Wright – one of Bo Bardi’s beloved masters – mimicked the fluent contours of the urban Jardims, where the houses were located. Refined through a long heuristic drafting process, the form also satisfied the architect’s confessed temptation to experiment – experimentation that justified the small financial returns on the commissions. As seen in the plans, such speculative exploration did not concern the function as much as it did the form.

On the other hand, a vernacular economy, based on the rational relation between the exploitation and application of local resources, grounded both the construction and material facets of the houses. They each endured the whims of tropical weather thanks to the usual features of traditional Brazilian architecture: thick brick walls tied through lumber beams, timber porches covered by dense shrubs of heather and generous openings protected with timber lattices in Casa Valéria Cirell; and, limited sun exposure on its wider windows and a configuration favouring cross-ventilation in Chame Chame House.

Details designed with recycled materials give a primitive accent to the houses. The most significant are the mortar of stones, shells, fragments of tiles and even parts of dolls; rendering experiments for the external walls. Such canvasses of treasures can be seen as an extension of the picturesque collection the Bardis stocked at the Casa de Vidro. Inspired in the trencadís used by Antoni Gaudí – another of Bo Bardi’s most admired architects – this lithological finishing preluded the Brutalist drift that her design work underwent after she completed the projects of both dwellings.

Furthermore, it instilled in the houses a phenomenological dimension that one could root in the extra-sensorial experience of the candomblé, a practice that Bo Bardi, it is said, secretly embraced at home. Admitting the growth of autochthonous plants, the same shingle walls fostered the integration of the Casas Valéria Cirell and Chame Chame in their originally wooded surroundings. Though the progressive urbanisation of the context curtailed the houses’ environmental integration, it also favoured their symbolic integrity as mysterious remains of a bygone epoch.

Together, the form, construction and material of these residences ensured their foundation in the physical, cultural and economic enclaves where they were built. Also, they signify a tribute to human dignity that the architect, moved by her national and progressive spirit, felt committed to pay throughout her career. For their part, the locality and symbolism of the dwellings epitomised the sociopolitical base of Lina Bo Bardi’s work. Ultimately, they singled out from within the history of Modern architecture, a more sensible way to reach the universal.

Feature article by Silvia Perea.

You Might also Like