Beyond Environment

Share

This past northern hemisphere autumn, curators Emanuele Piccardo and Amit Wolf teamed up for Beyond Environment, a small, meticulously researched and highly rewarding exhibition at LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions) on Hollywood Boulevard.

Focusing on a decade of production roughly centred on May 1968, Piccardo and Wolf mined more than half a dozen little-studied archives across Italy and the US to unearth a trove of rarely seen materials related to Allan Kaprow’s Happenings, Robert Smithson’s land art, Gordon Matta-Clark’s architectural interventions and the varied activities of Italian superarchitetti, a loose network of characters and collaborations operating in the orbit of the University of Florence that included such names as Superstudio, UFO, 9999, Ugo La Pietra, and Pietro Derossi. To make sense of this motley of material, the curators constructed a kind of Venn diagram of transatlantic radicalism and discovered at its centre the Italian architect Gianni Pettena, whose interdisciplinary activities in Italy and the US unfolded in close contact with his contemporaries in both countries and provided the linchpin that held Beyond Environment together.

The irony of locating Pettena at the centre of anything, given his staunch commitment to the periphery, gradually became palpable at LACE. Born in 1940, Pettena graduated from the University of Florence in March 1968, into the hothouse of political and disciplinary disillusionment that gave rise to Superarchitettura and its later, more museum-friendly incarnation, Architettura Radicale. The latter movement is now widely known thanks in large part to the expert packaging of projects such as Superstudio’s Continuous Monument (1969) and Archizoom’s No-Stop City (1969-72) for publication by the architects themselves and for exhibition by curators such as Emilio Ambasz, who assembled Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, a major presentation at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1972, and Germano Celant, who coined the phrase ‘Architettura Radicale’ to title his contribution to that exhibition’s catalogue.

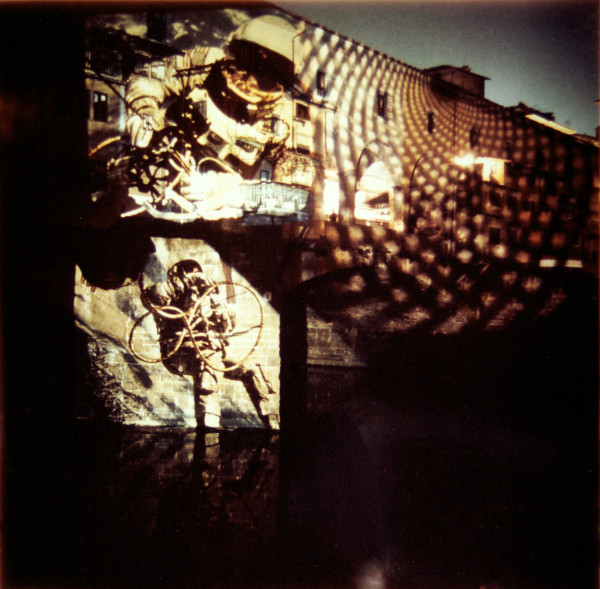

And, though they staged important exhibitions in Pistoia in 1966 and Modena in 1967, the superarchitetti voiced their dissatisfaction with the status quo most powerfully in the streets. In 1968, for example, 9999 staged a Happening in Florence that consisted of multicoloured projections on the Ponte Vecchio [Fig. 1]. For Campo Urbano, a 1969 group intervention in Como, La Pietra inserted a cellophane-wrapped wooden construction into a busy pedestrian thoroughfare in a similar attempt to redirect the occupation and perception of the city.

The UFO group, in its various Urboeffimeri of 1968, deployed polyethylene inflatables to redefine the contours of the urban fabric, to communicate graphically its criticism of the establishment and, it turned out, to provide protection against the police who arrived to put a stop to their activities [Fig. 2]. Pettena, in his 1968 Trilogia, organised collaborators to march through the streets of Novara, Palermo and Ferrara carrying two-metre tall letters spelling out politically charged phrases (‘carabinieri’, ‘milite ignoto’ and ‘grazie e giustizia’) which, owing to their ephemeral cardboard construction, began to disintegrate from the moment the marches began [Fig. 3].

Pettena and the other superarchitetti drew obvious inspiration from the Happenings that Kaprow had been staging since the late 1950s. They also fell under the sway of a growing interest in semiotics among Italian architects of the period, particularly as advanced by Umberto Eco, who taught in the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Florence in the late 1960s. But even at this early stage, Pettena was not entirely convinced by the critical stance adopted by his contemporaries, and from the start seemed to operate at some remove from other superarchitetti. In his contribution to Campo Urbano, for example, Pettena strung laundry through the main square to call into question both the hierarchical status of the piazza and the choice of La Pietra and others to frame their work within that space. Further distancing himself from the group, Pettena declined an invitation to participate in Ambasz’s 1972 MoMA exhibition, instead staging a solo show at John Weber’s New York gallery a few months before.

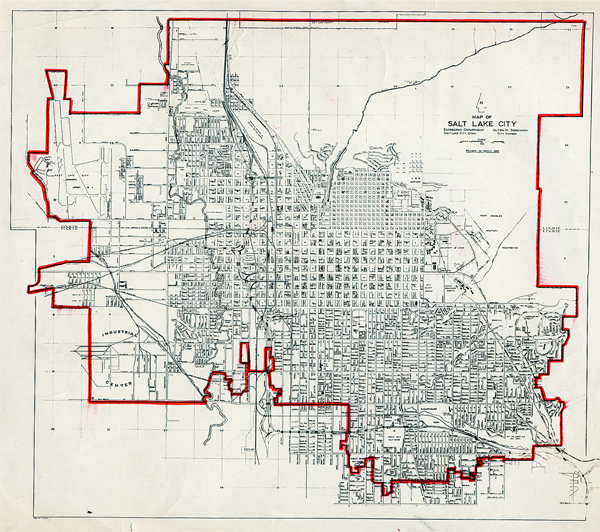

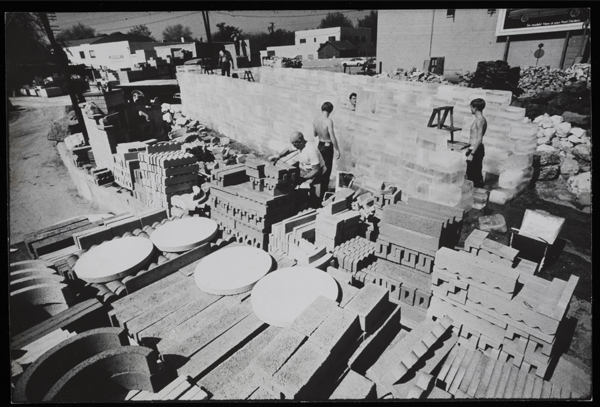

At the time, Pettena had already been in the US for some time, having been awarded residencies at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design in 1971 and the Department of Architecture at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City the following year. In Minneapolis, he completed two Ice Houses, encasing a derelict school building and an unassuming single-family house in thick layers of ice [Fig. 4]. In Salt Lake City, he produced Clay House, another of what curator Amit Wolf dubbed “entropic envelopes”, Tumbleweed Catcher, a large wooden frame designed to accumulate the ubiquitous Western plant, and Red Line, a performance during which he traced the political boundaries of Salt Lake City with a line of red paint [Fig. 5].

As with his Italian projects, Pettena’s US work resonates closely with Kaprow’s earlier performance pieces. The Ice Houses, for example, take clear cues from Fluids, the Happenings Kaprow staged in Pasadena and Los Angeles in 1967 [Fig. 6]. But where Fluids melted completely, leaving little more than a puddle as an in situ trace of the event, each Ice House left behind, at least temporarily, an architectural ruin.

Pettena’s insistent marking of his activities on architectural form, as well as his growing interest in entropy, destitution and the periphery, took him in a different direction than his Italian contemporaries and established important links between his work and that of Matta-Clark and Smithson. Asphalt Rundown, Smithson’s 1969 confrontation of a decidedly less than virgin landscape on the outskirts of Rome [Fig. 7], resonates closely with Pettena’s Tumbleweed Catcher, while Matta-Clark’s operations on an existing vernacular structure in A W-Hole House (Genoa, 1974) echo Pettena’s earlier Ice Houses. In an even closer parallel, Matta-Clark founded the Anarchitecture Group in New York just months after the publication of Pettena’s book, L’anarchitetto: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Architect, in 1973.

Fig. 6: Allan Kaprow, Fluids, Pasadena and Los Angeles, 1967 (photo by Julian Wasser. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles)

Though Matta-Clark likely arrived at the concept of ‘anarchitecture’ independently, such accidental encounters are crucial to the exhibition. In 1971, for example, Pettena reconnected with Smithson, whom he had met in Rome years earlier, while out for a walk in Minneapolis. Their chance meeting led to an illuminating dialogue, originally published in Domus and reproduced in the Beyond Environment catalogue. One of Smithson’s laconic quips says as much about Pettena’s US work as it does about his own: “I’m interested in bringing a landscape with a low profile up, rather than bringing one with a high profile down.”

Another neatly encapsulates the kind of work Piccardo and Wolf were drawn to for Beyond Environment: “Somehow to have something physical that generates ideas is more interesting to me than just an idea that might generate something physical.” Indeed, the most powerful projects in the exhibition – a 1969 Living Theatre performance at the Space Electronic discothèque, Pettena’s Ice Houses, Smithson’s Asphalt Rundown – recuperate destitute sites by evacuating deterministic meaning in favour of amplified surface effects.

To their credit, Piccardo and Wolf did not attempt to recreate the immersive immediacy of the work they studied and instead adopted a more clinical, documentary point of view. Archival materials – mostly small-scale preparatory sketches, diagrams and photographic documentation of events – were arranged with framed documents on the perimeter walls and video projections restricted to three undulating surfaces commissioned for the exhibition from Pentagon, a group of recent graduates from the Southern California Institute of Architecture [Fig. 8].

Fig. 8 (above and below): Pentagon, Sonic, Los Angeles, 2014 (photo courtesy of Amit Wolf)

With Beyond Environment and its elegantly assembled catalogue, Piccardo and Wolf produced a nuanced body of work that adds significant depth to the growing scholarship on the Italian radicals of the 1960s and ’70s. Throughout, they orchestrated a carefully controlled distance between viewers and the work on display, with layers of mediation and framing (both physical and didactic) that left the audience with little doubt that the interdisciplinary radicalism that fired these diverse artists and architects has long since been domesticated.

In the ensuing decades, most of the architects on view have adopted a more conventional professional posture and largely faded into obscurity. Pettena, who has spent the intervening years operating more as an artist than an architect, made a similar point in 1973. In a group photo of the short-lived collective Global Tools, he donned a placard reading, “Io sono la spia” (I am the spy). The gesture placed him again at the periphery, this time of a group of ageing radicals on an inexorable trajectory of assimilation into the very disciplinary machinery they had initially set out to resist. In Hollywood, the point was made most poignantly by Pentagon’s media surfaces, which erupted from the floor like a tidal wave only to curl back in on themselves and resolve politely back into the very ground from which they sprang.