Cold rush: climate control

Cold rush: climate control

Share

When it comes to climate control, Australian architects are going to ground for inspiration. MEZZANINE steps back in time to discover how our future is panning out.

It is impossible to ignore the impact the late-1800s rush for gold had on Australia’s architectural heritage. A new-found wealth saw the Victorian and, more specifically, Boom style home become a beacon of prosperity – lining our streets with the decorative façades of what we now call the terrace house. Even Melbourne’s Royal Exhibition Hall was built to show the world the wealth we had discovered, later becoming Victoria’s first World Heritage-listed building. Stepping beyond the subsequent eras of Federation and Art Deco, these homes have become the starting point for most architects, filling our regional towns with a character of the not-so-distant past.

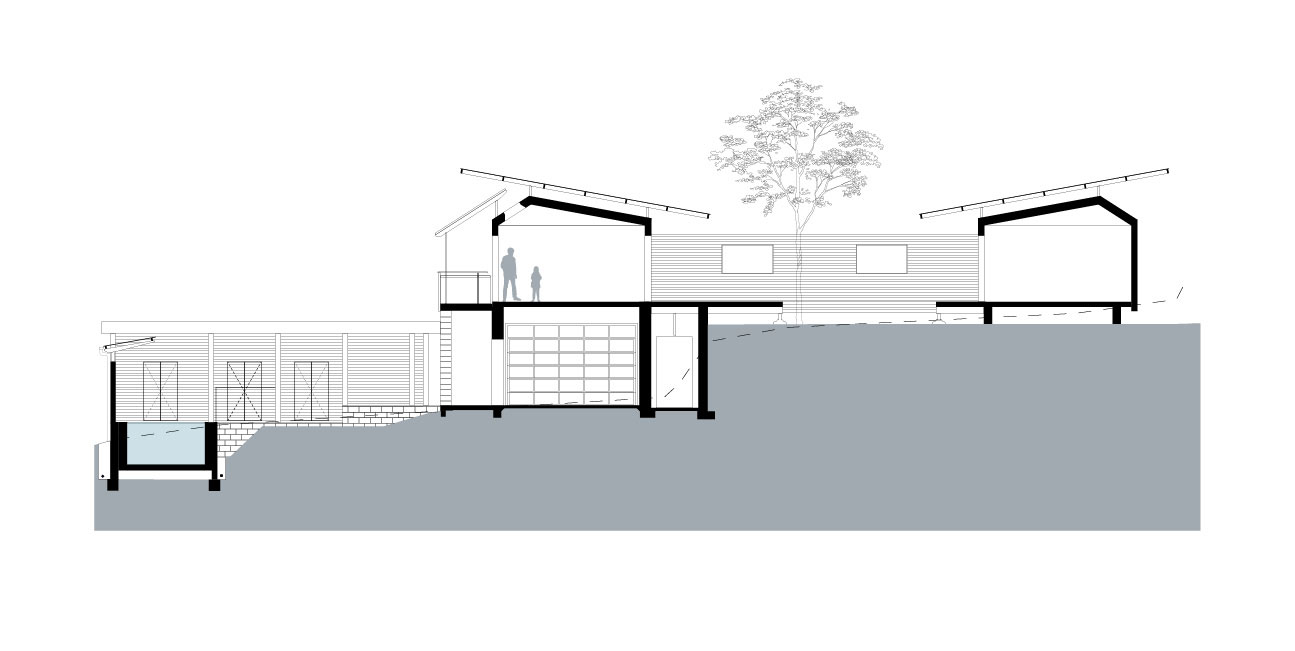

The section of Desert House in Alice Springs by Dunn & Hillam.

Digging a little deeper into the gold rush, we rediscover the great Aussie invention, the Coolgardie safe, designed by Arthur Patrick McCormick in the late 1890s – created to keep food cool in the extreme temperatures experienced in the remote Western Australian town that provides its name. It is a simple concept, thought to be derived from the way Aboriginal people used kangaroo skins to carry water, and relies on three simple elements: wind, water and heat. Today it is better known as evaporative cooling. For more than half a century, the verandas of many Australian homes featured these early makeshift fridges, many made from hessian and wire mesh.

For Alice Springs-based designer Elliat Rich, her Coolgardie Line furniture brings a new level of opulence to this iconic piece of rustic Australian ingenuity. A finalist in the 2015 Australian Furniture Design Award, Rich’s work brings together references to the past and present, creating works that showcase the every day in a local context. It is nothing new to position a house so the breeze keeps things cool, or even elevate a structure to encourage air flow. In fact, the iconic Queenslander is an architectural form derived purely from this function, as is the great Australian woolshed which has inspired the likes of Stutchbury and Murcutt when they head out of town.

Part of the Coolgardie Line by Elliat Rich, a finalist in the 2015 AFDA award.

Similarly, the concept behind McCormick’s low-tech invention is at the heart of exciting new thinking in the approach to energy-efficient buildings. In the small NSW town of Junee, architects Dunn and Hillam, together with a local council brave enough to explore possibilities, has created a public library with an energy bill of less than most households. To understand the way this is achieved, you would think you would need to borrow a few physics textbooks, though the system is actually incredibly simple. Water that is harvested from the building’s roof is resprayed over the roof during clear nights, reducing the temperature of the water down to approximately eight degrees. This water is then used to cool the building during the day. Called a night-sky cooling system, in essence it is a Coolgardie Safe at a grand scale and the first of its kind in Australia. It is expected to pay for itself in just four years.

The Junee library by Dunn & Hillam. Photo by Killian O’Sullivan.

Dunn and Hillam’s commitment to energy-efficient buildings is long-standing, with their 2009 Airies House, a contemporary farm-house on the outskirts of Junee, providing the growing family with a home where the only visible climatic control is ceiling fans. Derived from the ideas behind grain silos, farm buildings and that other rural icon, the Akubra, the house is arranged under a large roof that drops low to the ground, reducing the impact of wind and sun. Using hydronic geothermal heating and cooling in the floor, the home is virtually self-sufficient with solar panels used to power the pumps that circulate the water.

Further afield in Alice Springs, these same architects have designed the Desert House, another leading example of low-tech ideas being used to manage climate. Using a concept usually found in campgrounds, the house incorporates a fly roof that creates a void, a little like the double skin on an old Kombi. As the warm air rises and escapes a breeze is created by drawing cool air from the rock beneath the house, channelling it through a series of well-placed windows. In the still, arid conditions of Central Australia, a naturally-generated breeze is rare, so one which reduces the internal temperature of a house by up to 15 degrees without the use of air-conditioning could be considered an architectural miracle.

Airies House in Junee by Dunn & Hillam Architects. Photo by Killian O’Sullivan.

Returning to Western Australia, Luigi Rosselli Architects have recently constructed Australia’s longest rammed earth wall along the edge of a sand dune in the remote Pilbara region. Behind the 230-metre-long span, constructed using only materials from the site, are 12 apartments – home to musterers who work on the cattle station for short periods of the year.

Titled ‘the great wall of WA’ and buried beneath the dune, these homes are at one with the earth, utilising the thermal mass of their natural surrounds to keep them cool in a sub-tropical climate that often experiences temperatures above 40 degrees. Topped with a meeting space and chapel that features cyclone-proof curved sliding glass windows, the project provides a safe haven for its residents while reducing energy costs and maintenance in the off season.

‘The great wall of WA’ by Luigi Rosselli Architects. Photo by Edward Birch.

The project, which is gaining recognition globally, rejects corrugated iron roofing, a material typically used in rural buildings and central to the work of iconic Australian architect Glenn Murcutt. In doing so, it is raising questions about the materials we commonly use and exploring new possibilities for an Australian architectural vernacular. As Murcutt himself said: “You know, if we set out to design an architecture that’s Australian, we’re in trouble … The important thing is that we address the issues, we address the landscape, we address the brief, we address the place. If we address those things and do them rationally and poetically at the same time, we must be getting somewhere.”

This article originally appeared in MEZZANINE issue 6 – available online and digitally through Zinio.

You Might also Like