The legacy of William Toomath

The legacy of William Toomath

Share

Text: Jack Davies

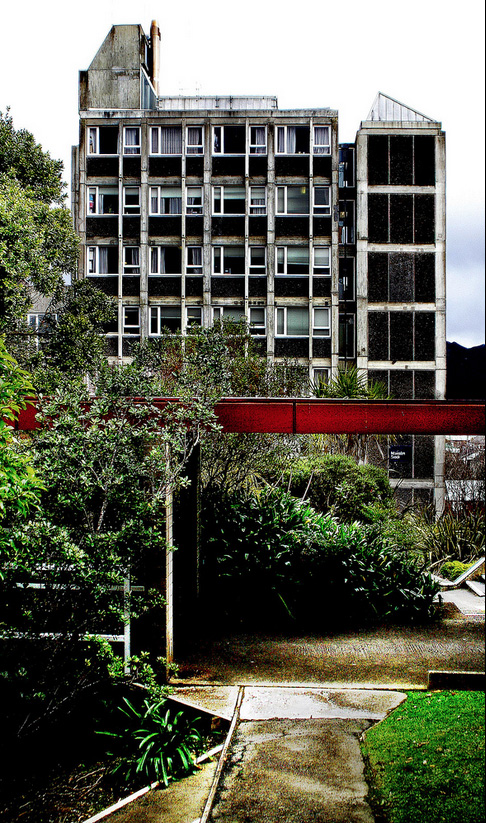

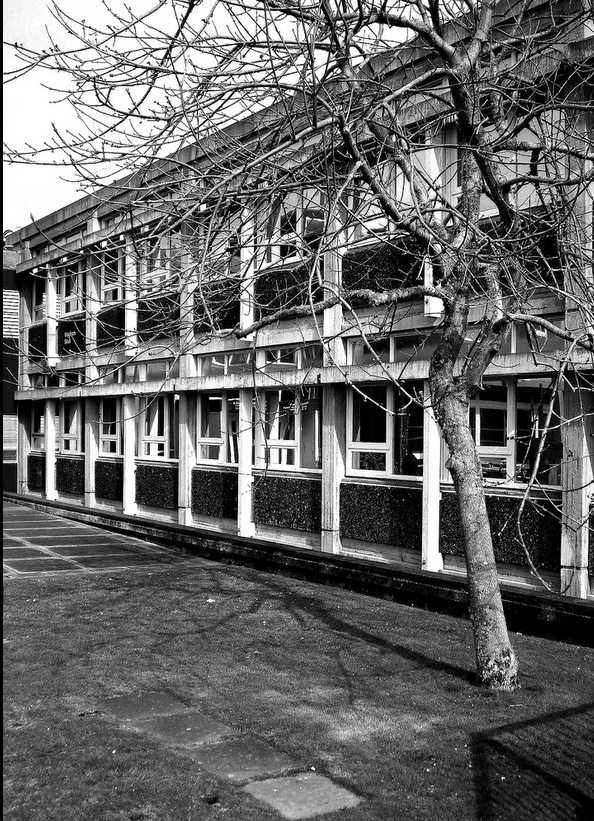

Above image: Karori Teachers College, Stage 1 + 2. Image courtesy of Michael Dudding

In last month’s article I focused on modern architecture in a Maori context – the Aniwaniwa Visitor Centre by John Scott. This month marks the passing of one of his contemporaries, and colleagues – Stanley William ‘Bill’ Toomath. A cross-section through his work is a fitting segue into New Zealand Modernism and his route throughout reveals a fascinated and dedicated man. First, as part of the Architectural Group and later, in partnership with Derek Wilson, Toomath produced an impressive body of work that has influenced many contemporary New Zealand architects. He died on 20 March this year, aged 88.

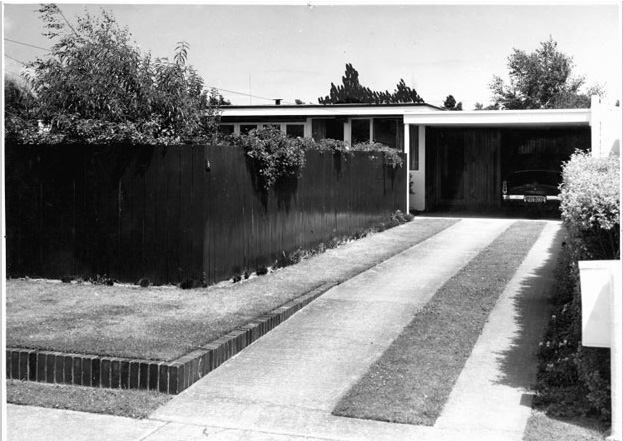

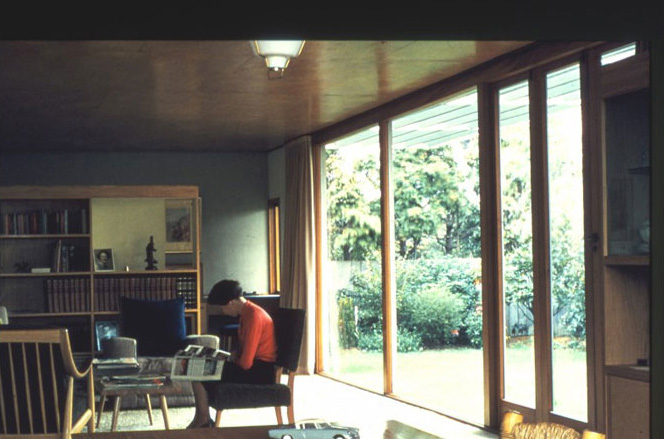

Toomath designed his debut house for his father on a typical neutral site in Lower Hutt. The site was totally devoid of outlook and surrounded by similar 120 feet by 50 feet plots – the same that spanned the country. In an attempt to create every part of the site liveable and enjoyable, he shunned placing a compartmentalised state-style house in the centre of the block and instead divided the site into a series of courtyards. The eventuating floor plan has a view axis from each corner of the site. Moreover, the glazed facades bookended by courtyard gardens were a welcome respite from the gabled, tight houses usually associated with suburban Lower Hutt.

The house is honest in its expression of materials, which, according to Toomath, is emblematic of New Zealand. The house was the subject of an exhibition at the City Gallery in 2010 – a fitting tribute to the lasting conceptual appeal of an attempt to break free of the suffocating solid and void diagram that is suburban planning.

Bill was born in 1925 in Lower Hutt, and worked for two years at an architectural office in Wellington before moving to Auckland to study architecture. His arrival in 1945 coincided with an Auckland scene struggling to come to terms with post-war rations and inflated construction costs, but he and his other second-year student colleagues recognised a vortex in New Zealand architecture – well designed, easily built vernacular houses did not exist, moreover, there were more state houses and borrowed styles from overseas.

One of the leaders of the Group, Bill Wilson, said that New Zealanders were aware for the first time since the war and were asking ‘what makes us New Zealanders different from, say, Australians?’ He challenged the architects to answer: ‘is your house a New Zealand house?’ The Group evolved into an office that changed the way New Zealanders thought about their own architecture, and is the subject of an incredible book by Julia Gatley, called Group Architects: Towards a New Zealand Architecture.

A Fulbright Scholarship meant that Bill could attain a Master of Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. He was one of 16 students in his class, which was conducted by I.M. Pei, and one of his fellow students was American architect John Hedjuk. In the documentary Antonello and the Architect, Toomath reminisces on Pei being a ‘clear headed and still very youthful fellow, adventurous and very capable’. He talks about a challenge Pei set them of designing a shopping mall that was three times the size of anything built in America at that time, just to ‘bend’ the minds of all the young graduates, before revealing that he had just been commissioned to do that exact project in his office.

Toomath’s residential projects were generally lightweight timber constructions that required reasonable masonry work. However, he often received clients who had small budgets but very strong opinions about design. One of his clients, who had emigrated from England, wanted a European-style stone house. Toomath’s past experience made him resist the idea at first, but soon he attempted sinking a rectangular slab into the ground with a white-painted masonry wall that nearly reached the ceiling height, erected on three boundaries. The sunken box was wrapped in timber and offset to contain the bedroom, kitchen, bathroom and study. The change in level served to delineate between public and private though the entire house as such embraced an open plan living. The Mackay House in Silverstream ended up winning a NZIA Silver award.

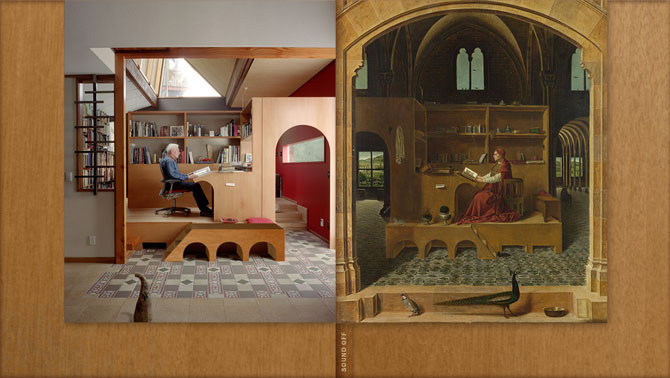

His own home was built on what is a seemingly repetitive story in mid-century Wellington – low-cost construction in a heavily bush clad, cliff-adjacent site exposed to the vagaries of the weather. Facing the Oriental Bay, the house is a three storey timber structure clad in vertical redwood. Toomath sunk a portion into the hill and simply erected the remainder on stilts. He had an obsession with a single painting for a number of years, Antonello da Messina’s Saint Jerome in his Study c. 1474. While painted in elevation, it had enough shifting light qualities for Toomath to recreate da Messina’s depiction of a study in his own home, including custom tile patterns. Toomath’s house continues to evade the weather by eschewing unnecessary eaves; a low maintenance icon that will continue to be visited well after his death.

His passing ends the career of one of the last purist modernists in our country. While having studied Le Corbusier and been trained by the likes of Pei and Gropius, he had a more contextual mindset, at odds with his mentor’s ideals that modern architecture consists of a singular superlative design that can provide a solution to any site. Context as a mindset is burned into any architect living in the nightmare that is Wellington’s topography, and perhaps mid-century modernism built with detailed respect for its sheer site constraints and idiosyncrasies is the closest we have to a local architecture.

Toomath was one of the first New Zealand architects to study at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and to bring this highest level of overseas design knowledge to local conditions, budgets and scope. His buildings were undeniably pure modernist, but his open spaces bled into each other with a finesse that made them domestic and his continual use of timber provided warmth and texture. His relentless pitch to save heritage buildings placed him at the moral tip of our industry and with a polarising love for a folly, his work is foremost in our modern architectural heritage.

You Might also Like