Revisiting the residential work of Charles Correa

Revisiting the residential work of Charles Correa

Share

Written by: Ian Nazareth, Images courtesy Charles Correa Associates.

Charles Correa, 1930–2015

The atmosphere in India in the 1950s and 1960s was instilled with a profound sense of optimism in the role architecture might play at a critical stage in nation building. In an era when Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Louis Kahn et al completed significant commissions, Charles Correa returned to India to set up his practice. Along with his contemporaries, architects who were not seduced by the dogma of modernism, Correa discovered a resonance with Indian tradition and a call to discover a distinctive architectural language.

This aeration of values followed a rigorous process of assimilation, especially as he sought to reconcile his experiences in the US, a legacy of local architectural history dating back millennia and the opportunity in this new landscape. Correa was critical of the disjunctions in the conceptual nature of architecture, caught between the singular, predominant thematic and the scenographic, architecture composed of relentless yet discontinuous spatial experiences.

Correa’s architecture is fraught with such tensions that seek to incorporate latitudinous ideas, even ideologies. Latent in the work is the profound synergy between the mythical and physical, bringing together traditional relationships with built forms, patterns in societies and the semantic of modern architecture. The projects are cast with the backdrop of deeper socioeconomic issues, the rising density and inequity in Indian cities. The architectural syntax, particularly the elements of the floor plate and the open-to-sky space in Correa’s work, become powerful devices to operate through and across these conditions.

The Tube House (1961–1962) was Correa’s Maison Dom-ino and an early example of a model for climatically responsive mass housing. The clarity of the proposition conceals a sophisticated understanding of the climate and domestic programs. Located in Ahmedabad, the row house expands on the typology of wind catcher homes, a response to the hot, arid climate. The inclined roof, openings and circulation funnel convection currents through the house, releasing them through a central internal courtyard. Despite its modest footprint, the introduction of level differences generates thresholds that inherently resist the regularity implicit in micro living.

The staggered floor alludes to a ceremonial pathway and the symbolism of journey in architecture, with the shifting axis allowing the disaggregation of spaces. These might be barriers of defence against the climate or varying degrees of privacy for living spaces. Influenced by Hindu and Imperial architecture, Correa identifies open-to-sky spaces, from the roof terrace, the courtyard to the lawn, as vital to the lives of people, at every level of the socioeconomic spectrum. Historically, they have accommodated most domestic uses. Paired with this sectional dislocation, the sky is a protagonist forging complex spatial relationships throughout the work. In the contemporary city this contiguity is profoundly generous and gestural.

Conceived as two individual tubes, the Parekh House (1967– 1968) expands these variables. The conceptually distinct modules, dubbed a summer section and winter section, were to be used at different times of the day. The summer or day section, with deep shades, contained living and dining areas, while the winter or night section held the bedrooms that opened onto terraces.

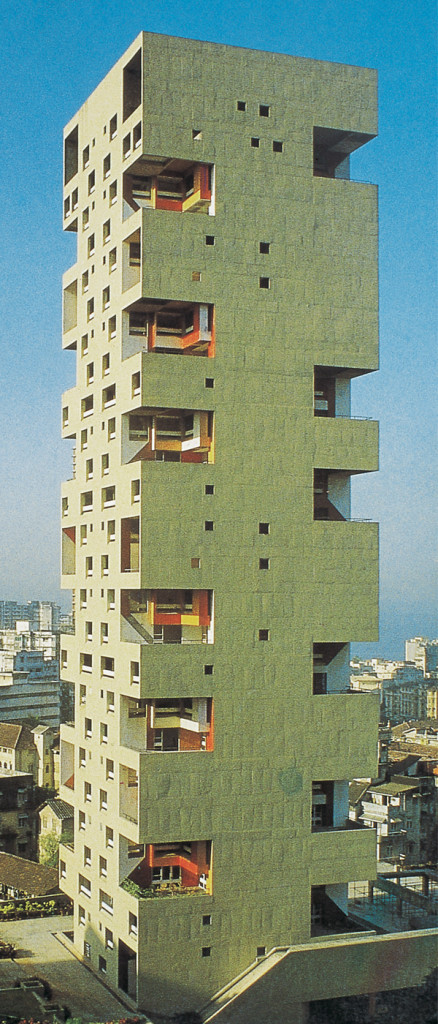

With the completion of Kanchanjunga Apartment Building (1970–1983), the tacit relationship of floor and sky is intensified, through scale and complexity. The multi-residential tower appears as an austere object in Mumbai’s skyline, a silhouette punctuated by deep double-height volumes subtracted from its mass. Its minimalist sheer walls mask the dovetailing of enclosed spaces, with balconies and the interlocking of individual apartments within the tower. Here again we see Correa’s definitive parti, the intricate displacement of distinct functions within the house through the use of various levels. The differentiation creates a hierarchy of living areas clustered around pavilions that frame the sky. As a multi- storey residential tower it remains a rarity in the city. Oriented to exploit vistas to and breeze from the Arabian Sea, the project responds to the region’s weather, wrapping living areas with decks, shading them from the harsh sun and monsoon. The project presents a typological hybrid, the distinctiveness and responsiveness of a bungalow within a high-rise tower.

Correa’s work immersed itself in the city through architecture, advocacy and, most notably, urban planning. The transference of architectural form to the fabric of the city was crucial to designing in emerging contexts and contested landscapes. The courtyard and the dwellings became a generative instrument for urbanisation.

Correa cautioned against the deficiencies of urban planning in Bombay and, in response to the Development Plan for Greater Bombay (1964), he led a proposal to restructure the city. Bound by water on three sides, the city’s only potential for growth was to the north. In contrast to Bombay’s sporadic and organic growth, the proposition across the harbour was for a planned satellite city, integrating Bombay with the hinterland. New Bombay (now Navi Mumbai) was a significant step in the development of the megacity, opening a new paradigm and development strategy. As the chief architect for New Bombay, Correa revisited the open-to-sky area, the doorstep and community space as an organisational structure, in conjunction with Buckminster Fuller’s adage to ‘rearrange the scenery’. The city unfolded from these first principles, where neighbourhoods and spatial sequences were a unit of growth.

The Incremental Housing project (1983–86) in New Bombay that followed was a tactical response to affordable housing development and he experimented with low-rise developments yielding higher densities. In the ‘new city’, Correa proposed seven detached houses that varied between 45 and 70 square metres, assembled around a courtyard. As they did not share common walls they could be expanded individually. The cellular growth of residential modules is directed by the footprint and shared open-to-sky space, with the private residence rescaled to a micro-community.

It is rather unfortunate that much of the built body of residential work predates the vertiginous growth and liberalisation of the Indian economy. Correa lamented the role of unobstructed market forces in the destruction of cities, a systemic issue in Indian cities and a debatable concern for the architecture of cities globally.

At a point when residential typology is staked on the consolidation of type, Correa’s contribution to the community of spatial practice is one operating laterally across scales and projecting residential projects into the wider gaze of the city. In this regard Charles Correa’s body of work is noteworthy, a resolute trajectory emerging from the experimental micro-living, vertical bungalows and the city at large. Critical responses to spatiality, incremental development, climate, materiality and poetics are fundamentally linked. The resonance across typologies, suggests a potential and possible vectors for residential projects within the architecture of the contemporary city.

You Might also Like