Peter Stutchbury’s Gold Medal tour comes to Melbourne

Peter Stutchbury’s Gold Medal tour comes to Melbourne

Share

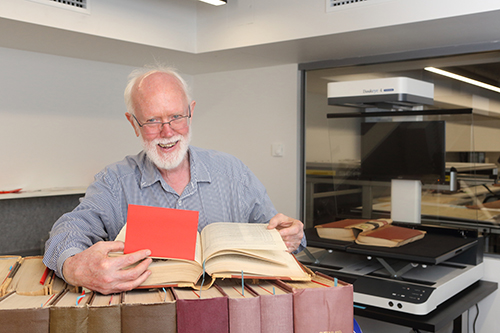

Article by Amelyn Ng. Image above by William Staffeld.

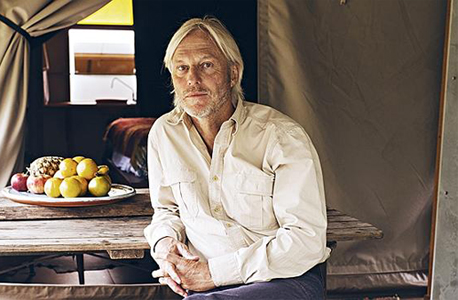

Sydney architect Peter Stutchbury is in Melbourne speaking for the first time, having been invited to share his vast body of work as this year’s Gold Medallist. The basement theatre at the MSD brims over and the air is buzzing with expectant chatter. As Peter begins to speak in his collected and somewhat-mesmerising voice of reason, the room quietens almost immediately, and by the end of the two-hour talk he succeeds in capturing and earning the respect of virtually everyone in the audience.

Peter has a very sensible-yet-experimental approach to architecture: always in respect to the landscape, its geology and its climate, while also proposing low-cost sustainable alternatives and ensuring the continuity of specific indigenous and rural cultures. From top-soil to tap roots, Peter’s first-hand knowledge of the Australian environment is incredible- yet he explains them in layman’s terms with no trace of alienating technical jargon. His unceasing commitment to inter-generational education is also in itself something to be admired: “in order to keep it, you’ve got to give it away”. His repertoire of teaching appointments overseas span the continents: from China to Kenya, his design expertise in rural environs is sought by students and professionals alike. Yet unlike many globally recognised practitioners, Peter still prioritises local roots, making time for a professorship at the University of Newcastle and co-leading the famed ‘Total Immersion’ student summer school held annually at Pittwater, NSW.

From his presentation, it is evident that childhood experiences in the bush have profoundly impacted his design philosophy today. A city dweller all my life whose bulk of architectural ideas are formed through careful observation, accumulated knowledge and theoretical engagement, it is deeply moving to see an architect so connected with the land and country that design moves can be ‘felt’ intuitively, not by reading or studying it at arms-length: but by raw, physical immersion. Peter often camps on site prior to any conceptual formulation, asserting that it is impossible to do a project without knowing the site nor its client well (something of a challenge for architects in the global age). He describes the “detail of a place”- not of man-made articulation and form, but of the ingenious design mechanisms of trap spiders, frogs and artesian water from which he draws inspiration. He likens the role of an architect to that of a surfer or camper: always ‘looking for a site’, always ‘watching weather patterns’. He speaks fondly of a quote made by his mother that encapsulates what Peter stands for- not just toward architecture, but his outlook on life itself: “I want you to have the knowledge of the city, but the truth of the country”. His professional and personal beliefs have become so aligned that the country ‘conscience’ and construction as inseparable sides of the same coin. Peter seems not only to be practising architecture as a profession, but also living out its principles: his life is as open and honest as the structures he creates.

His easy-going yet direct manner carries on throughout the presentation, where crescendos of dead-serious intensity are softened by casual humour that restores ease in the room. I suspect this ability to deliver sober intent and an uncompromising philosophy alongside geniality, humility and camaraderie, is the true reason he is held in high regard almost evenly across the private, public, pedagogic and professional spheres. An hand-sketching advocate, he is surprisingly not vehemently against digital technology, yet outlines its limitations on human emotion and spontenaeity: ‘you can’t hug a computer’. Also somewhat unexpectedly, Peter does not remain exclusively in the realm of rural Australiana- in fact he travels extensively, and has traces of Japanese influence n his work. The rest of his work is guided by what could be termed expressive pragmatics: making architectural gestures of standardised structural components, service-walls, ‘outside kitchens’ and passive heating and cooling devices such as verandahs and rainwater-walls.

His lecture is full of lessons lived and learned: of responsibility to native country, to education and to contextual relevance. The notion that architecture owes itself to nature, and by extension to the natural, physical comfort of its inhabitants, is difficult to fathom and even more so to implement in an age resigned to HVAC environments and increasingly-fragmented procurement methods. How do these principles fit with high-density living, large practices founded on overseas work, and siteless, digital (even hypothetical) student projects and competitions? What about relatively new countries like Singapore whose topographical makeup is being heavily altered by land reclamation and whose society has virtually no relation to country nor rural conditions? Perhaps the intrinsic Australianness of Peter’s architecture is its great success- not to necessarily be superimposed nor emulated point-for-point in other contexts, but to serve as an exemplar of refined contemporary architecture whose roots are found nature, without the literal bluntness of a green aesthetic nor indiscriminate application of vegetation. The word ‘sustainability’ is not used once in his lecture. And as Peter closes his presentation, he reminds everyone to stay “in touch”- not with his architectural work or future endeavours, but with this nation’s greatest resource, the land that surrounds us.

Stay tuned for Part Two of Amelyn’s insights into Stutchbury’s Melbourne Gold Medal trip, which will reveal his insights shared at the Gold Medal Breakfast event, organised by EmAGN for emerging architects and graduates the following morning.

You Might also Like