Interpreting the Melbourne School of Design

Interpreting the Melbourne School of Design

Share

All images courtesy of Peter Bennetts.

The Melbourne School of Design (MSD) at the University of Melbourne, designed by John Wardle Architects in collaboration with Boston-based architecture studio NADAAA, has been described as ‘representing the values of the university’ as ‘built pedagogy’. Such comments suggest that buildings can convey meaning, that they form a narrative.

Whether buildings can be ‘read’ has been debated for more than fifty years, with no convincing conclusions yet. The Poststructuralists provided the most compelling argument, indeed Jeffrey T Nealon in ‘The Swerve around P: Literary Theory after Interpretation’ (Postmodern Culture, Volume 17.3, 2007) suggested individual interpretation outweighed the importance of the product. Assuming for a moment that it is possible to read buildings, what is the font? What are the elements of architecture that not only the users, but also the consumers of architectural media, read?

Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure would ask ‘what are the signifiers?’ Following this line of investigation, does the configuration of elements (signifiers) contribute to the narrative to allow us to understand what is being signified? These are all questions of the representation of architecture.

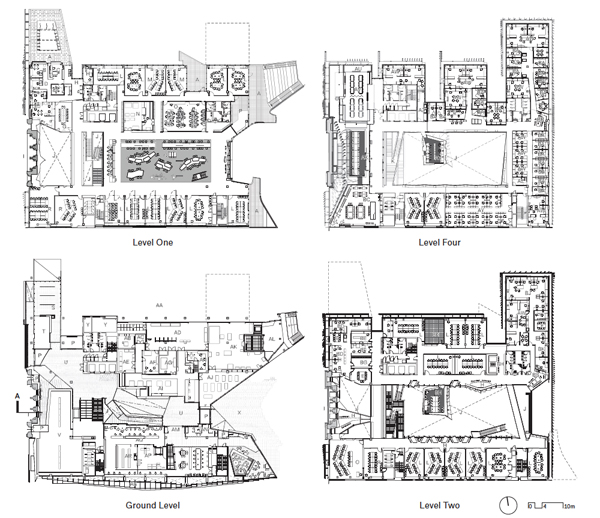

Like a find-your-own-adventure novel, there are multiple ways to experience and interpret the MSD building. It sits as a hefty volume of many chapters on the site of the former architecture school, a building experienced in the round and approached from various directions. Each façade takes on a different character, including a remnant historic elevation of the former Bank of New South Wales. The ground level façades are transparent, providing glimpses into exhibition spaces, the library and workshops, which open directly onto a public courtyard.

The ground level conceptually invites passers-by to participate in the life of the school – although with power tools roaring there may be the odd OH&S issue with crowd participation. The internal cross route via the inner workings of these spaces is open to all, but unless otherwise advised some would remain blissfully unaware of the configuration of the school above. While those in the know access the school internally via a wide stair with tall-blackened steel balustrade, others enter externally from a traversable amphitheatre. One level up from the everyday life of the campus is the signature internal space of the school: the Design Hall, MSD’s social epicentre. It is here the primary plot is immediately revealed: a four-level, top-lit atrium with an exquisitely detailed coffered timber structure from which ‘hangs’ an intriguing folded form.

However, given such an important space is not obviously shared with the life of the university, it questions the transparency theory and the values it suggests. The Design Hall is the most challenging space in the project; the obvious reading is it represents the collective heart of the school. The generous galleries that circumnavigate the space are equipped with quirky seating and collaborative worktables attempt to act as the studio spaces the budget did not allow for, but the culture of a vibrant architecture school demands. Nader Tehrani (NADAAA) notes that ‘once the budget deemed it impossible to provide dedicated studio spaces, with one desk per student, the design mission was transformed to creatively redistribute the net-to-gross relationship of the building […] to carve social spaces and spaces of learning in what is conventionally the space of circulation’.

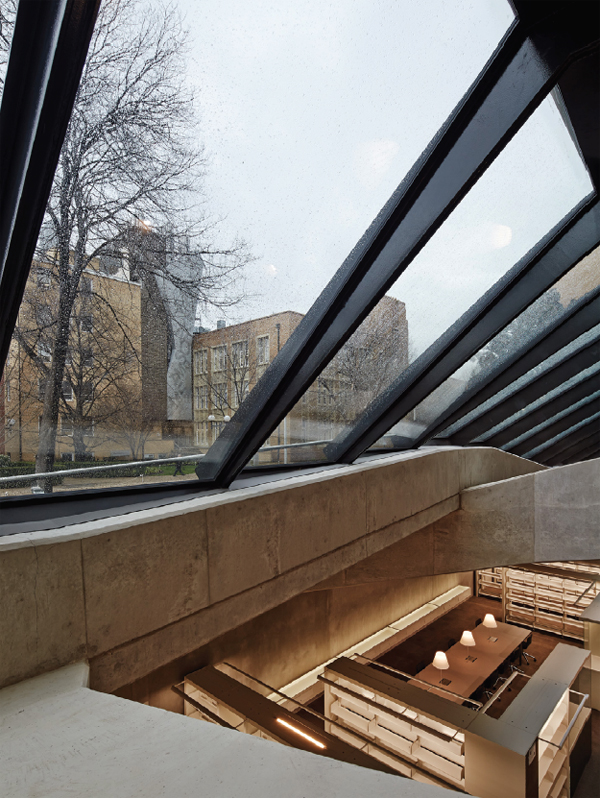

The galleries allow for views across the space and down to the lower level, visually connecting people and animating the interior. This strategy is de rigueur in contemporary shopping centres, off ices and academic buildings that embrace Herman Hertzberger’s social agenda of the 1960s. The quality of detail across the project is exceptional; more refi ned than either of the architects’ other design schools. The material palette, particularly the Design Hall, is sophisticated and sombre, lighting and furnishings border on the domestic. With the addition of plants and a water feature the space might even resemble the wonderful atria in a number of hotels by John Portman in the 1970s. Of course every book has multiple readings. One is that students take great delight in the idea that someone will always be looking out for them and that there is much to be learned from others occupying the space. The opposite take is that it is overbearing. The curious floating timber form could be mistaken as the school’s central surveillance centre contained in an inverted conning tower.

First year students arriving for day one of their course might think that big brother is watching. With few spaces to escape the gaze of others, it is easy to imagine the most popular lounges on the lower level of the Design Hall being those under the suspended meeting spaces or within them.

The language of architecture is a particularly difficult one, not everyone can read it. Before text, ancient cultures relied on oral histories from informed elders to understand their stories, values and laws. In our discipline too, the voice of the architect must be considered. John Wardle responds to the question on the possibility of the building to be read as ‘built pedagogy’, noting ‘it’s really more about evoking a sense of curiosity’. While in some instances, such as the library’s expressive beams and the basement window that showcase the retaining walls, the ‘built pedagogy’ is obvious, there are numerous interesting moments of intense detail and craft in both the envelope and interior that prompt both ‘how did they do that?’ and the rhetorical ‘why?’. It is this sense of intrigue that is the most successful strategy in the project, one that prompts the reader to flick back a few pages and check they have not missed something.

Unlike novels, buildings take on a different life once they are occupied; their stories are constantly rewritten as occupation patterns defy the intent of the architect and their clients. Thus the fable of MSD is not yet complete, perhaps it never will be. Its next edition will be partly autobiographical as thousands of students are yet to make their mark. Like a much loved novel, this building will become better with age; when the pages are dog-eared and stained with red wine and coffee, it is likely to be even more intriguing. Pick it up again in a few years – it will remain significant and represent an ever-evolving history.

Review by John de Manincor for Architectural Review Asia Pacific.

You Might also Like