Big ideas for tiny houses: interview with Paul Morgan Architects

Big ideas for tiny houses: interview with Paul Morgan Architects

Share

Image above: Cape Schank House. All images courtesy Paul Morgan Architects.

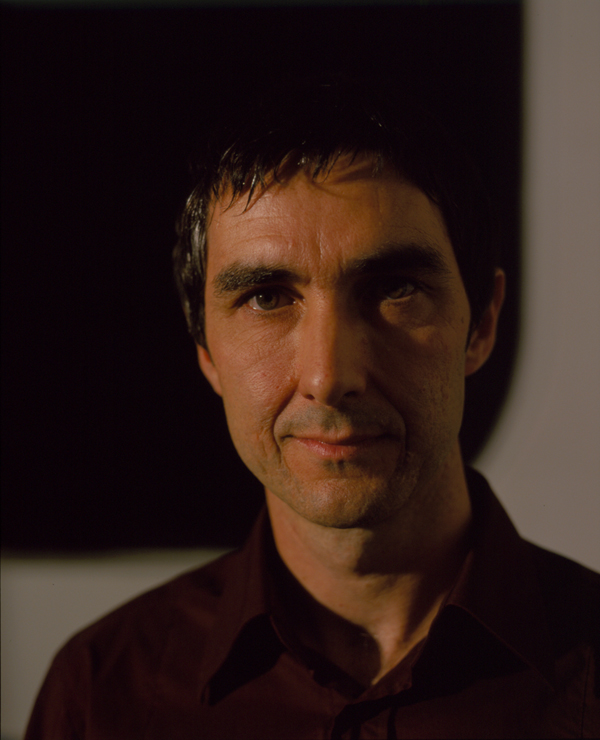

Melbourne-based practice Paul Morgan Architects approaches projects with a highly unconventional blend of science fiction, sustainability and speculation. Director Paul Morgan spoke at this year’s AIA National Architecture Conference on ‘The Changing Role of Risk in Architecture’. Peter Salhani interviews Morgan for AR 140 – Small Spaces.

Peter Salhani Paul, you’ve said you don’t really see your practice as being about ‘small-scale architecture’ but you’ve attracted considerable attention for a couple of very small projects – Cape Schanck House on the Victorian coast and Trunk House in Victoria’s central highlands. What fascinates people about projects of this scale?

Paul Morgan Well, I don’t know if it’s necessarily about scale, it’s maybe more to do with people being obsessed with houses because everyone can relate to them. Our small projects, and they are mainly houses, have been the most experimental architecturally and perhaps that’s why they’ve attracted the most attention.

PS Both projects are small compared with the average Australian contemporary home: Cape Schanck House is 135 square metres, Trunk House is approximately 65 square metres. Both are deeply organic in their origins. Tell us the big idea in these tiny houses.

PM Well, Trunk House is a weekender for a professional couple. We were lucky with our clients, who had been to Barcelona and were impressed with Antoni Gaudí’s La Sagrada Família and its bone-like structure that uses a kind of thickening in the joints to carry the high loads. In discussions with structural engineer, Peter Felicetti, on how we could adapt that for Trunk House, we initially talked about composite fabrication, or steel encased in latex, but it all seemed quite forced. So we went back to first principles and the forest ecology.

Initially we thought we’d use dead branches found on the forest floor, then someone hit on the idea of using branches with forks in them – technically termed ‘bifurcation’. That was our Eureka moment. We collected a mix of hardwood forks from nearby farmland and national parks (you can get a licence for that), but we didn’t want it to be a rustic cabin – another rude building in the bush. It took a lot of technique to translate what we collected into the finished structure – using steel dowels to piece together the latticework of timber forks/columns to create a big truss. And there was an artist involved in carving and sculpting the forks to harmonise the joints.

PS Experimentation is the territory of trial and error, but in architecture it is not as permissable to fail as it is in research. How do you as architects minimise risks along the way, or deal with idea failure?

PM With this project it was mainly to do with the people involved: we had an excellent conceptual engineer, great clients, a sculptor and furniture-maker, who carved the bifurcations over about a 10-month period. But there were still risks involved. The council initially failed the framing, but the engineer proved to council that the members he designed (150mm-diameter posts), were equivalent to 90mm F17 hardwood posts and actually exceeded the design load bearing capacity – and council accepted the explanation.

PS Cape Schanck House won the RAIA Robin Boyd Award in 2007, another tiny building with a big idea at its core – literally – with a rainwater tank in the middle of the space to collect roof runoff and cool the interior. Talk us through that idea.

PM There are two ideas in that house actually. One is the water tank being the locus, the central point of the house, instead of the plasma TV or fireplace that you’d typically expect. When you study architecture you’re taught to get all the water off the roof and out to the edges, so it seems counterintuitive to bring all the water inside, but that’s essentially what we did. The second idea is about the ‘performance envelope’. The shell of the house scoops up and down one side to both draw the prevailing winds in to cool the interior, while shading it at the same time. So there’s a kind of aerodynamic effect that is partly about form but also distended form, responding to quite a harsh environment.

PS With your larger projects, such as the South Melbourne Market roof, Chisholm TAFE’s Automotive and Logistics Centre and the Emerald Hill Library and Heritage Centre refurbishment, how do you orchestrate smaller moments or elements that humanise them with a sense of craft, allowing people to connect?

PM Larger projects are perhaps not so much about craft but form-making. At Chisholm, for instance, the big thing was the aerodynamic form.

PS A metaphor for high-speed motion?

PM Exactly. It’s not about intimacy at all; it’s about anchoring the building to its location with a form that references its function. The question of creating intimacy… is not just about scale or materials, it’s a mix. For instance, with the library project, the big gesture was the height of the roof and bringing it into the space, where it comes into close contact with people. That’s a bit of form-making, but the use of tactile materials are what created the domestic scale, which was important for this, being a children’s library. If we’d done it in a shiny metallic material, it would have failed.

PS We started with the intrigue of the experimental, so tell us about your Blowhouse project – another big concept contained in a small footprint.

PM Well, it’s a speculative project, created for a 2008 exhibition at the Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery about theoretical design. It’s set in 2030 and assumes that climate change has rendered the environment so hostile it’s barely habitable. We named it Blowhouse: Life Support Unit and it poses a similar question to the film Alien – about terraforming – how do you create a habitable environment?

PS So how does Blowhouse support life?

PM It has a skin, a semi-rigid exoskeleton of recycled rubber, that moves with prevailing winds. Then there’s a kind of lung that affects the exoskeleton as it ‘breathes’, which in turn affects actuators that produce electricity through three sources: solenoids, wind turbines and photovoltaic cells. Yes it’s a futuristic look at housing. But maybe there’s no clear line between the theoretical and the practical. Fifteen years ago, I possibly wouldn’t have thought I could build something like Cape Schanck House, but we achieved it. In a sense all projects are speculative until they’re built.

PS Would you really like to build Blowhouse – or was the pleasure in its conception?

PM Well, I’d love to try … I’m an architect in search of clients.

This interview appears in AR140 – Small Spaces, available at selected newsagents, Google Play or Zinio.

You Might also Like