Are laneways the answer to densifying our cities beautifully?

Are laneways the answer to densifying our cities beautifully?

Share

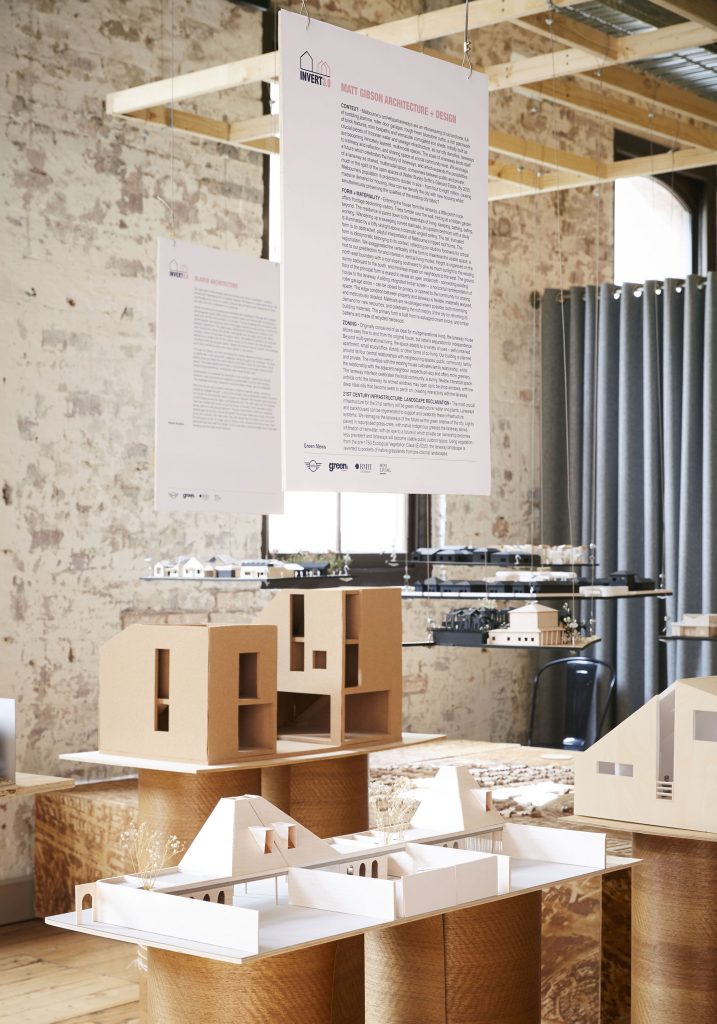

Last year, green magazine and MINI invited architects to explore the potential of laneways as part of MINI LIVING – INVERT 3.0.

The architects were provided with a brief to design an independent dwelling on a piece of land carved from a suburban Melbourne block.

The goal was to create affordable housing in the inner suburbs, but the potential benefits of transforming the thousands of laneways and under-utilised back gardens in our cities extends beyond dollars and cents to touch on social isolation, the environment and smart design.

The ‘dead’ space dilemma

Transforming laneways into liveable spaces appeals to the concept of transforming a ‘dead’ space into something useful.

Matt Gibson Architecture + Design was one of the practices that participated in the thought experiment, presenting a tall, truncated form as an abstracted, playful interpretation of Melbourne’s hipped roofs.

The residence’s exaggerated verticality maximised useable space with the exterior hinting at a hidden garden beyond.

“Melbourne’s laneway are not being celebrated. They’re often secondary access spaces, places for cars, storage and garages, when they could be so much more,” says principal Phil Burns.

“We love taking something that’s already there and under-used and bringing it back to life to maximise its potential.”

“We’re cognisant of the impact that building new stuff has on the world.”

In Matt Gibson Architecture + Design’s residence this ethos extends to using re-salvaged cream bricks and timber battens made of recycled hardwood that “celebrate the history of laneways”.

Adaptive, sustainable design

“Living in a freestanding home with a garage and garden is not sustainable,” says Ben Edwards from Studio Edwards.

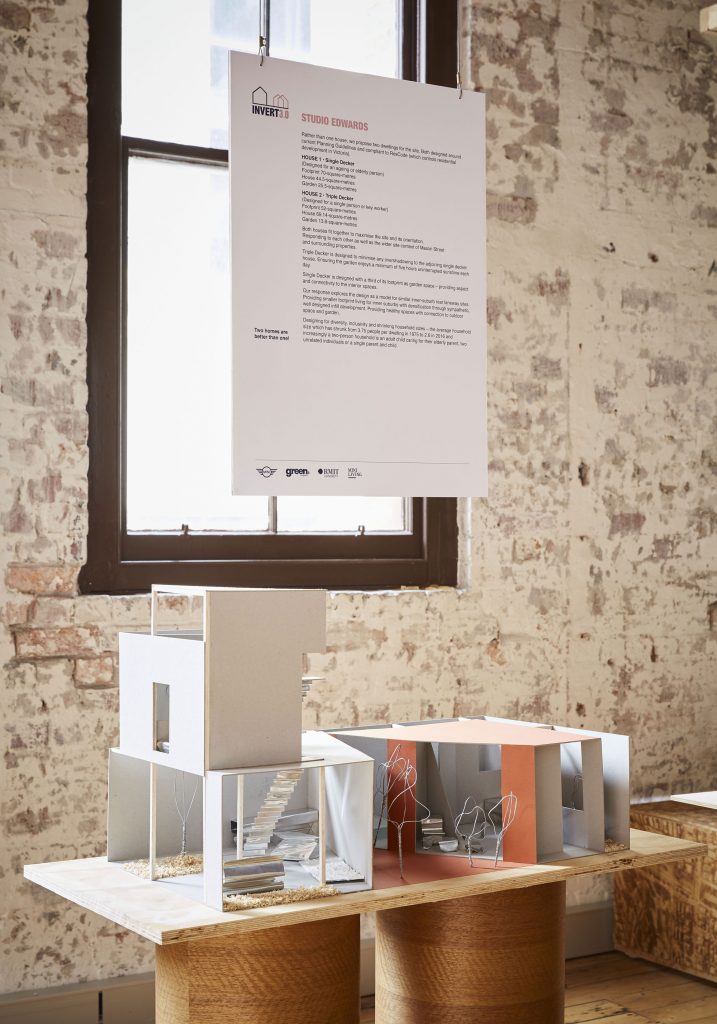

Studio Edwards also participated in MINI LIVING – INVERT 3.0. Its design proposed not one, but two houses, each adapted to a different demographic.

One property was designed for an older resident with a third of its footprint as garden space. The other was designed for a single person with plenty of natural sunlight.

“The average household size has shrunk to 2.6,” says Edwards.

“The future of good design is a flexible space that can shift and be adapted so the person inhabiting it doesn’t have to abandon the site and move on.”

The project provides an example of smaller footprint living for inner suburbs with densification through sympathetic, well designed infill development.

“There is this perception that smaller spaces are cheap, unexciting, but it’s the opposite. The badly designed houses and shoe box apartments we’re living in now are cheap and nasty.

“A laneway home gets rids of the unnecessary and pares down the living space to the essentials, so you get more value out of each square metre. It’s a pleasant densification of our city.”

Trading space for social interaction

Anyone considering living in a laneway is immediately wary about the lack of privacy that comes from being sardined in such close quarters, but Amy Bracks from IOA Studios says that’s something we need to get over.

“We need to embrace looking into each other’s spaces more than we do now. It promotes a sense of security and safety, but also a sense of community.”

IOA Studio + Alexandra Buchanan Architecture approached the brief by simply designing somewhere they, as young designers, would want to live.

They took the granny flat typology and flipped it, creating a simple structure that could be easily realised by a builder.

The design was paired back to little more than a bathroom and kitchen. The house could then grow with the occupant, allowing them to add rooms as required.

The designers also worked to make the ground plane part of the laneway itself, blurring the boundaries between public and private.

“We need to move away from wanting to own everything,” says Bracks.

“For our own mental wellbeing, we need to connect more with our community through shared resources. So rather than have your own garden, you can use the local park and connect with your neighbours there.”

The theme of isolation and community valorisation is something all the projects at MINI LIVING – INVERT 3.0 touched on.

The residences all invited its residents to have more of an open door policy, designing outdoor spaces and collective green spaces.

It’s a model that is also seen in the Nightingale project, where private laundries and gardens have been swapped for communal spaces.

The MINI Living concept explores how architecture and design can contribute to a brighter urban future and manifests in various events around the world.