In conversation with Satoru Sugihara

Share

Perhaps best known for his work as a computational designer at Morphosis Architects and as founder of ATLV, Satoru Sugihara is currently a faculty member of Southern California Institute of Architecture. His work includes the IGEO code source, entailing Agent-Based algorithm for generating cellular growth formations. Among his latest collaborations is Land of Hope, the China Pavilion For Expo Milano 2015.

This interview is occasioned by Agent-Based Computational Design, your first solo exhibition at AA[n+1] (9 June to 30 June 2015 ) in Paris, which just recently closed.

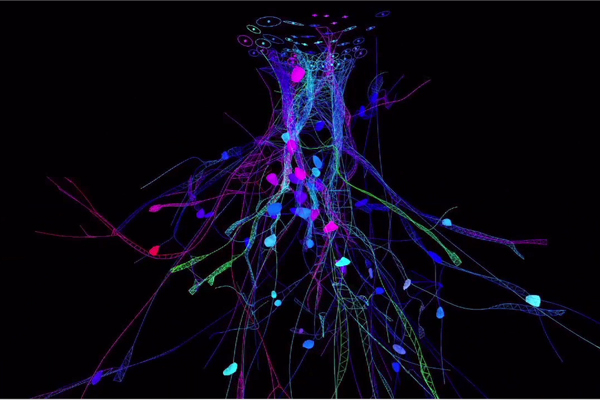

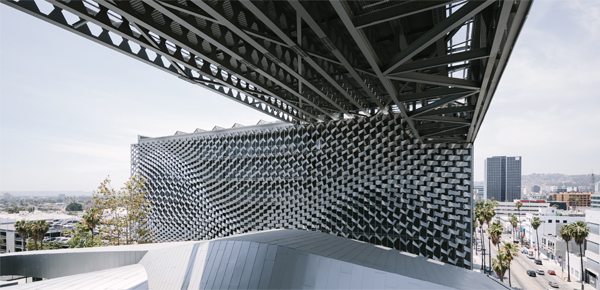

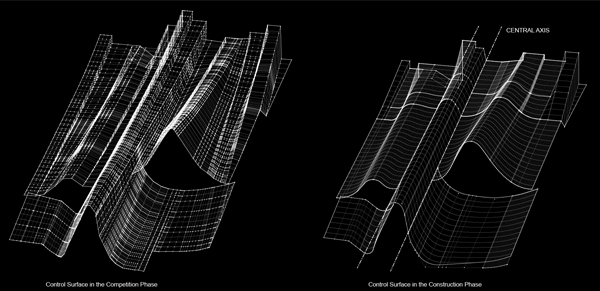

Agent-Based Computational Design is a design theory exhibition. I regenerated materials from my completed works, from built facade designs, agent-based architectural design studies to cellular growth algorithm researches [IMAGE 1]. The exhibition’s curators are Leslie Ware and Pierre Cutellic. There was no site-specific installation. A more abstract range was presented, with about half of the material regarding built work, the other half tracking my design process using algorithm research. It was a workshop where I demonstrated my open-source Processing library iGeo as well as a solo exhibition, so there was continuity at play between research and teaching [IMAGE 2].

You’re first continuous architectural collaboration was with Morphosis. A large section of the exhibition is dedicated to this period.

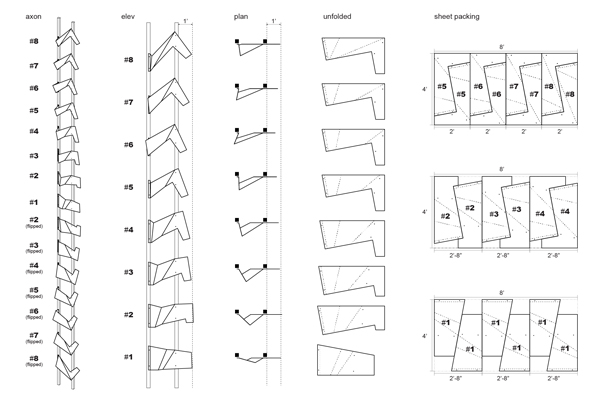

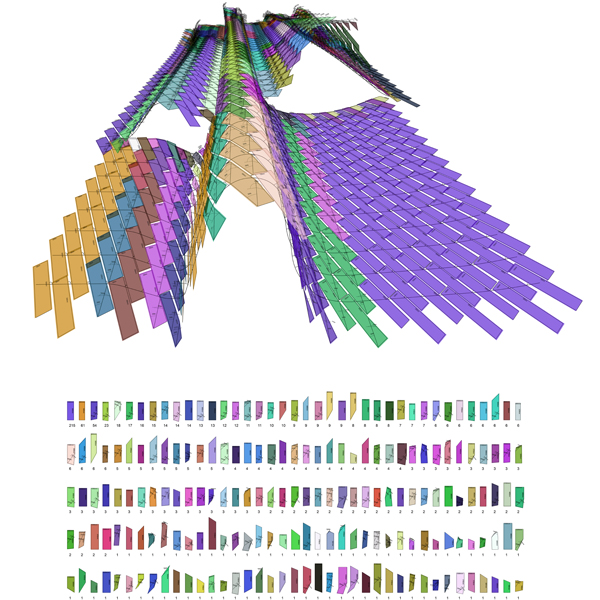

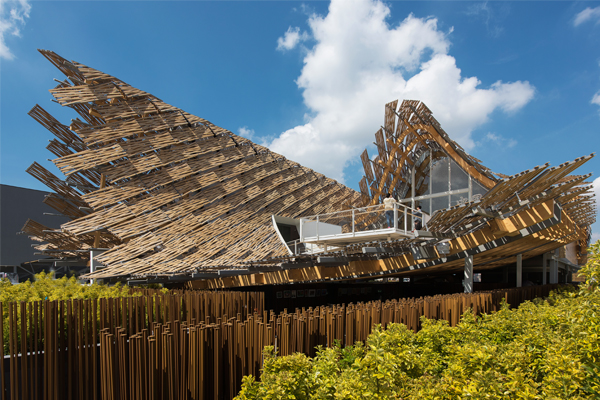

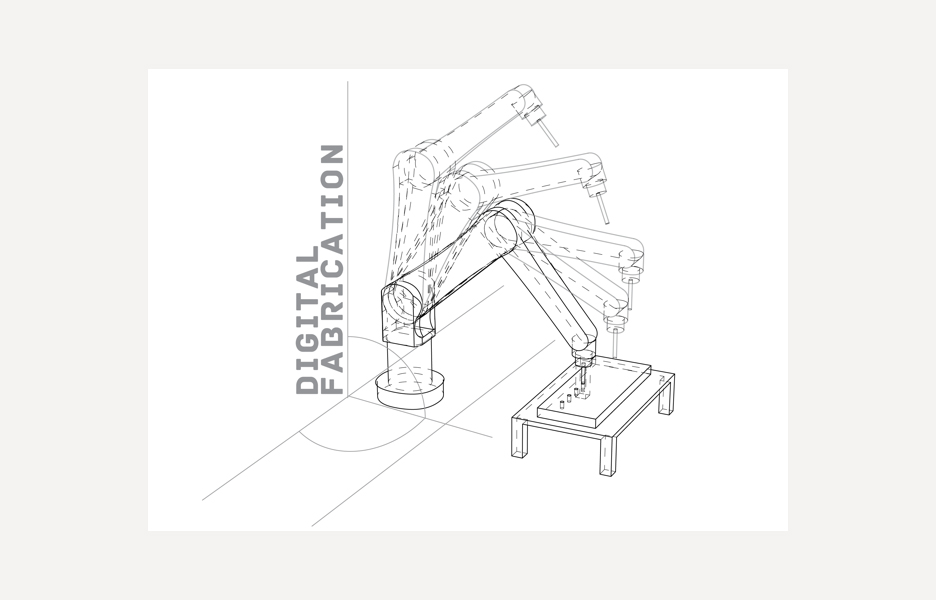

In Morphosis, we were a computation team with two-three designers. What is important is that there’s a complete freedom in Thom’s studio in terms of the software platform one uses, but you are responsible for how you can communicate with other software platforms and architects working in conjunction on very different set of questions. The drive now as before is fabrication innovation. Emerson College Los Angeles in Hollywood [IMAGE 3] is a good example. It’s a range of variously folded panels the unfolded shape of which is extremely rational minimising waste of materials [IMAGE 4].

In your latest work on Land of Hope, the China Pavilion for Expo Milano 2015, you helped merge the Italian Alps with Beijing under single, free span roof.

I was hired as a computational design consultant in the competition phase by Yichen Lu and his New York practice Link-Arc. My more intense work started in the design development phase. After winning the competition, we figured out the structure and gave the initial design its resolution also in terms of cost optimisation [IMAGE 5].

How much did you influence the pavilion’s final form? I’m asking because there’s a clear leap between the early surface form of the competition phase and the final computationally developed work. The long span exhibition space presented during the competition phase had irregular curvature, but this has become more rational in the later phases, so that both rolled forms are similar but distinct.

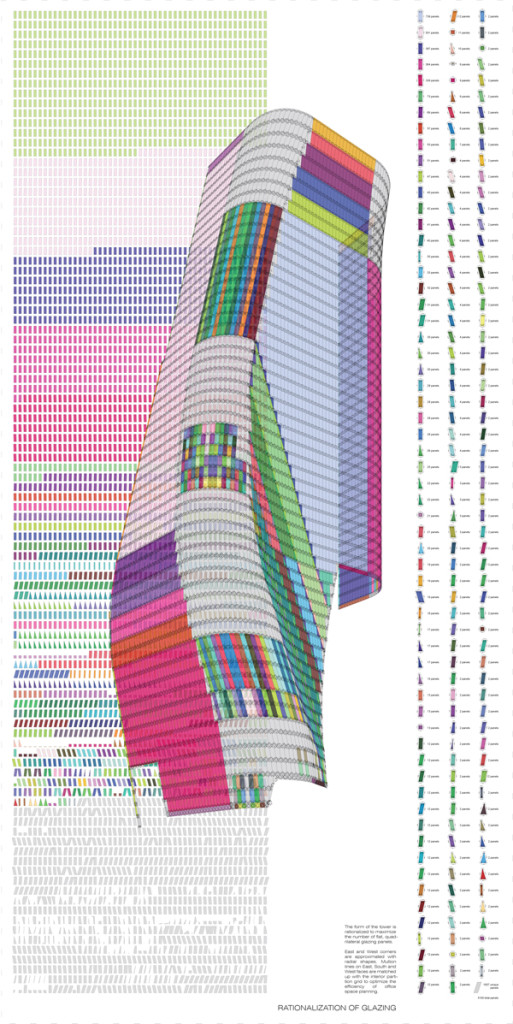

These are not rolled surfaces though, hence the complexity. They are driven from two sectional lines of mountain and city profiles. There’s no structure that can readily make up the whole. You could unravel the scheme in terms of surface form, of course, because it is still unidirectional, but it is not enough for making efficiently laid panels. I needed to massage the initial form to achieve a system and this is where the experiment in form comes from. It is about discovering parallel lines and flat surfaces. Yet it’s understated enough that you wouldn’t notice it, unless you look at the drawings, like you do now [IMAGE 6].

In the final reiteration curvature is more pronounced, as you say, but the effect is accidental, the result of the modelling method. Curvature in this case means panels are recurring steadily along a curve rather than varying in shape/size. This is driven from the method of computational modelling/optimisation I developed in Morphosis, so you can track some of this logic there, where form is reconfigured to accommodate the logistics of tessellation [IMAGE 7]. The next step involved rationalising the system as a structure.

And Yichen Lu was never too enamoured with one form over the next?

It is subtle enough. It’s not so much about form either but about the expertise and knowledge that computation brings when developing a coherent system, one that can negotiate flat and conical surfaces. There’s a grid system as well, of course, initially a diagonal one, then rectangular. The final panel is a folded rectangular shape. It is almost 90 degrees in this early reiteration in a way that can approximate the figure-form, but in the final reiteration it is a perfectly right-angled panel with folding lines – the optimised metal frame and woven bamboo surface [IMAGE 8].

This is the outer shell. Inside, a frosted plastic panel curves rather than folds to achieve the doubling of the shell. The materiality of this plastic is interesting. It offers an almost digital image of the same natural bamboo façade, a cloudy-grey digital filter if you want, which is befitting for Milan.

IMAGE 8: China Pavilion For Expo Milano 2015, View of Portal. Image copyright reserved with Sergio Grazia; appears here courtesy of Link-Arc

What is Agent-Based computation? Does it engage the latest computational developments in Deep-Learning AI?

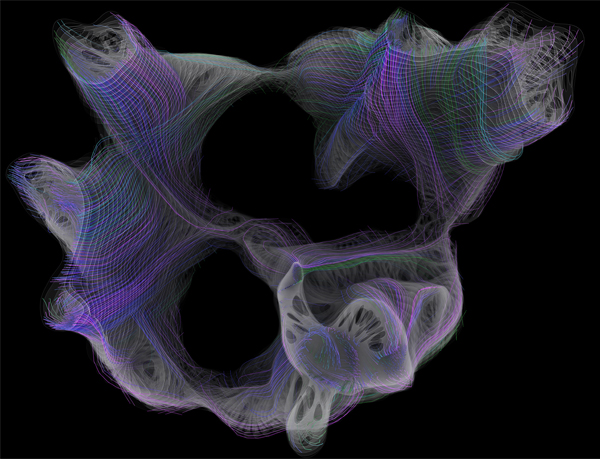

The two are not comparable. One, Deep-Learning, is high-level computation, the other is fundamental and basic. Before veering into the field of architecture, I was a computer scientist. I was dealing regularly and directly with machine learning and automation and I was exploring how these can tackle design or artistic intuition. For design generation and optimisation, AI methods like Deep-Learning entail training the AI for best design solutions. Bottom-up growth agents don’t care about such or this ‘best’. The programmer sets out the parameters, for example a voxel array for iso surface extractions or a system of curves. The model-system is there and the designer, Mayne is a good example, can then break out from the model, subverting it to great effect. AI is inherently different. For one, AI entails a mach larger model and the designer is therefore constrained to limiting a priori her space of action. This is the main reason why I opted for Agent-Based algorithms. From my experience, whereas the AI method dictates an a priori space, Agent Based work creates a space, one which is never given and therefore original, unexpected [IMAGE 9].

But AI has a training phase and one where you set your Skynet loose, isn’t it?

There’s an in-between space where you have to define a space for machine learning though. I went deeper into AI but it’s too time consuming. I decided to stay at the more fundamental level of Agent Based systems and do more in terms of design and build-ability. Today I’m interested in cellular growth, but even the development of an embryo to a baby is too complex. I stop much before. The Paris workshop was about cellular growth, a time dimensioned project. Cellular level biological behaviour is important for me right now. I am always aware that the biological bent is American. Paris is about mathematical rather than biological orders, so the conversation at AA[n+1] was refreshing. It made me realise how as a designer, I’m more interested in the fact that natural growth works. I care less about form. Nature works on a cellular level and if I can tweak it to make a straight line, for instance, then there’s an opportunity for architectural or other logics to come into play.

Deep-Learning neural networks are convoluted layers of topologies, which are indissoluble into a simple fundamental code exactly because of the rhizomatic links these layers then form. I can see the challenge for a programmer. But there’s an irony that much of your work deals with similarly complex spatial structures and layered orders. We’re all doing similar work in that sense.

For me, the amount of complexity of these forms is managed by computation. Only the output is important in both cases, form or deep-thought. I would like to understand more rather than less. You cannot rationalise a neuron system. I have no grasp of the brain and why thought emerges, but I can touch with my hand and computationally manipulate the systems I’m interested in and so achieve some of the design ambitions that are important for me today.

![IMAGE 1: Agent-Based Computational Design exhibition at AA[n+1] in Paris](https://www.australiandesignreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Image1.jpg)