COX’s Cliff Nichols on the business of a rebrand

COX’s Cliff Nichols on the business of a rebrand

Share

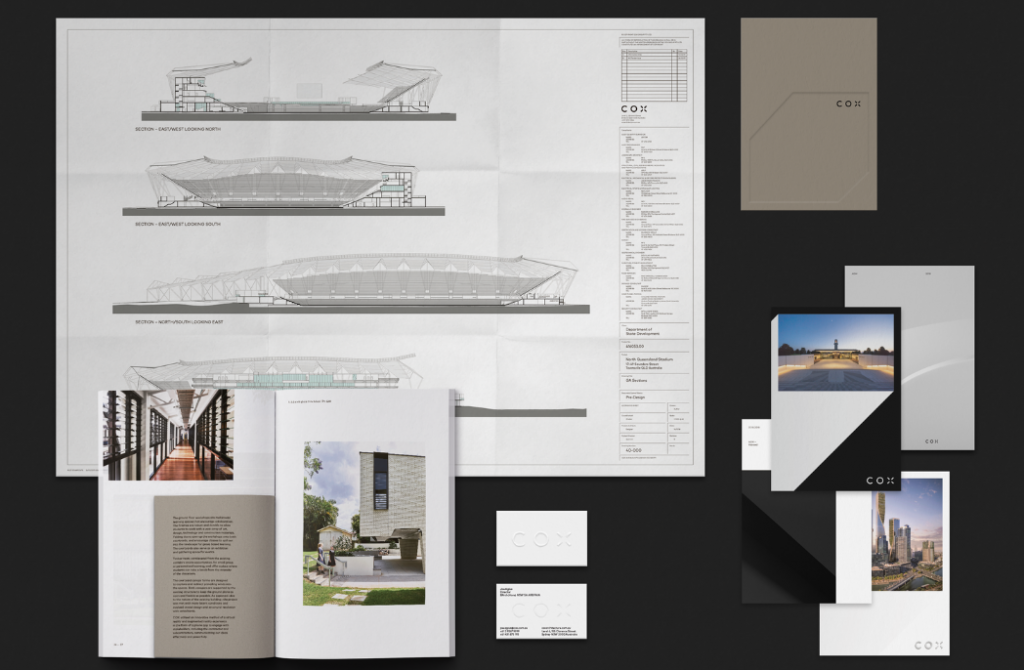

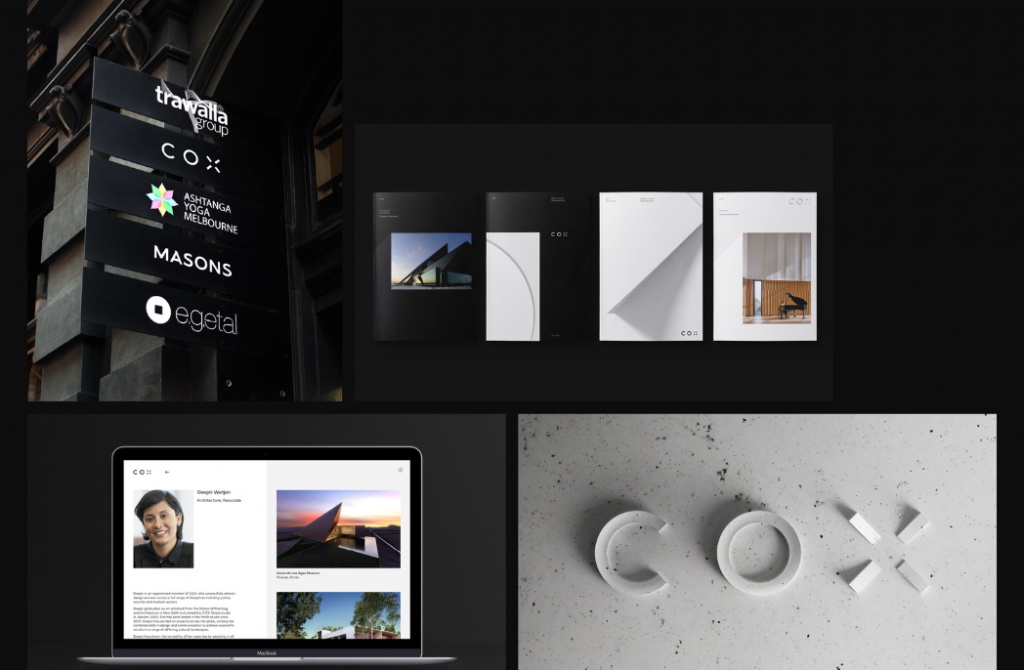

After more than 60 years in business, COX Architecture recently underwent a practice-wide rebrand, collaborating with creative agency VAN O to change much more than just its logo.

ADR sits down with COX’s head of marketing and communications, Cliff Nichols, to discuss the challenges of rebranding an architectural practice with significant history, a united and federated structure and 43 vocal owners, as well as how such an established practice stays relevant in the era of digital disruption.

ADR: What were the drivers behind the rebrand?

The drivers of this project were macro and micro, internal and external, clear and present, but also ambient and underlying.

Before we start to dissect these drivers it’s important to recognise that by most objective measures (scale, scope, revenue) COX has evidently done a pretty good job of adapting to change over its 60-year lifetime. Focusing on the past five years you could legitimately argue that it’s been more successful at adapting to – or even reframing threats as opportunities – than many of its peers. Credit to the organisation, this evolution was managed with day-to-day adjustments based on a sensitivity to context and backed by a collective will.

Despite the widely reported disruption in our space we’ve continued to grow and be successful, confounding the many doomsayers suggesting that the days of the architect’s influence were numbered.

This process of rebrand was sensitive to these external macro factors, but it’s important to recognise that the impetus for this endeavour came more from the desire for a clearer ‘sense of self’. This was partly a response to the need to compete more coherently across sectors and geographies. More critically, it was because of our desire to pause, take stock, look at who we were and who we’ve become, and to rationalise the things we collectively believe are important.

This said, you can’t ignore the pervasive challenges of globalisation, generational change, technology-driven redundancy, big ‘S’ sustainability, climate change, gender equality and myriad other society-level changes that reposition both what we do and how we should do it.

In fact, we identified early that it would be easy (relatively speaking) to knee-jerk and respond to each of these trends with a siloed policy or solution-focused task force –problems to be solved and boxes to be ticked, rather than acknowledging them as collective symptoms of a more fundamental shift. We understood that by approaching them piecemeal they might be ‘managed’, but would rarely be solved.

What we wanted to do was consider these questions holistically.

And to consider these in the context of identity and evolution, of what makes and keeps us, us.

After reading this it may be tempting to describe the exercise we undertook as the almost ubiquitous ‘search for purpose’. The big, external-facing statement that seems de rigueur in the business and marketing press these days. We made the conscious decision that rather than wrestle with the desire for a label and retrofit our thinking into a box we kept the page intentionally blank, wanting to see what would populate it when we arrayed our identity (who we are) against the changes we face. The words and their meaning were more important and useful than the labels traditionally ascribed to them.

Unsurprisingly (and reassuringly) a lot of the themes that emerged from our genuinely broad-based research were directly correspondent to the sets of challenges we were facing.

How important was it to consider the practice’s diverse portfolio of clients during the rebranding process?

We have an increasingly national (and international) client-base, so it seems a no-brainer that we should match our clients, right? A rhetorical question perhaps, but we quickly recognised that it was the ‘how’ of our response that was key.

‘Dots on maps’ and an ultra-consistent, ‘cookie-cutter’ presence was not how this practice was built, and nor did we think once you really examined stakeholder needs, that this was what our clients really wanted.

Of course, there are baseline elements of consistency of experience clients should expect, whether dealing with Perth or Canberra, Sydney or Melbourne, Adelaide or Brisbane. But this consistency relates to the issues of capability, access, commonality of tools and so on. The real value of COX, built on this baseline, is in the deep roots and intimate knowledge of context key COX people have in each of their respective jurisdictions, ‘local personalities’ in both senses of the phrase.

As such, each of our studios is both familiar, but also ‘of its place’, reflecting the character of its host city. This might sound like a truism applicable to any national practice, but the difference is reflected in our ownership and leadership: 43 directors of a ‘national’ practice, but whose professional focus is predominantly locally directed. We work cross-border and share when it’s valuable for our clients, but we don’t rely on ‘sector figureheads’ putting in the air miles and imposing a worldview on local contexts. Rather than a twist on the expected, the distinction is critical. If you review our organisation versus our peers then you’ll see what we mean.

This approach may actually be a disadvantage in the initial ‘sales’ cycle for us, but once through the initial slickness of ‘sector first, location second’ patter it quickly becomes apparent that if you’re seeking work that produces genuine civic apparatus more than benchmarked infrastructure, then contextual sensitivity is the trump card. Or at least, that’s what we believe. This isn’t justifying parochialism rather than a recognition benchmarking sector best practice is easier to deliver once you have a handle of the deep context of place, purpose and people for the intended apparatus.

COX participates in big and small projects at a national and international level. How does the practice deal with the pressure to grow beyond the confines of the Australia and are their risks in a practice trying to be all things to all people?

The squeezed middle is a position no one wants.

You lack the scale and profile of the internationals and ‘starchitects’, and the (apparent) edge and dynamism of this year’s ‘hot shop’. Compete with one and you can be positioned as ‘middling’ and ‘parochial’ and another and you’re ‘traditional’ and ‘cumbersome’. The task is obviously to show that we share the talents of both, but also provide something different and worthwhile.

This task is further complicated by the need, especially acute in certain cities, to team-up with a partner – big and/or small – to augment the offer and appease any local predisposition or mitigate some perceived risk.

COX is a ‘design’ practice. We have no interest in becoming a sidekick or glorified documenter. Consequently, we have had to say ‘no’ to approaches from internationals more often than we say ‘yes’. Which is no small thing. And of course, you then need to back up your position and justify the equality.

The evidence of experience, however, is that this is where we thrive.

Find a partner willing to actually partner and invariably the design outcome is better; we achieve more together than we would apart. So rather than diluting our ‘glory’, we accelerate our own learning and provide outcomes that are simultaneously more objectively world-class, but also retain the contextual response that has become the signature of our best work. Our work to date with UNStudio, Zaha Hadid at international scale and with CA Architects in Cairns or Architects 61 in Singapore at a more ‘local’ scale are proof positive of this.

Our own ‘global strategy’ also remains somewhat fluid, but completed landmark projects in France, Oman, New Zealand, UAE and China in the last two years would seem to suggest we’re doing something right. Our global footprint doesn’t follow any recognisable ‘regional penetration’ strategy, rather it reflects a marrying of work we’re both well-placed to deliver and really want to do. Chasing the dollars or volume for volume’s sake isn’t our route to success.

We’re now comfortable that we have the skills and sensitivity to mix it with the world’s best. Having seen what these superstars have to offer, we’re doubly sure that the design excellence that has brought remains the fuel for our future growth. Our collective task is about aligning capability with opportunity and then giving it everything. The other key component in this mix is having a local partner prepared to commit as we do to a respectful relationship over the life of any project, from day one to completion.

The practice maintains the name of its founder Phillip Cox, but is no longer led by him. Often, there’s a sense in the industry that when a practice grows beyond its founder principals, it can lose, in essence, the elements that made it successful in the first place. How do you avoid that?

Philip Cox is one of Australian architecture’s most pre-eminent designers and remains one of its most recognisable and vocal figures. He remains associated with the practice, but the truth of the matter is that COX, partly as a result of decisions Philip himself made, has long since moved on from being a ‘figurehead’ practice to one that is altogether more broad-based. In fact, within our 43-member directorate, we have three generations represented.

Rightly or wrongly, the perception within the professional community is that when a practice moves beyond its founder-principals and reaches a certain scale, usually the point where a level of decentralisation is necessary, is when it begins to lose its focus, its ‘soul’ even. At this point it stops being about ‘the work’ and starts becoming about ‘the money’.

As a short-form at COX this is referred to as ‘corporatisation’.

It’s a word that when spoken in our studios almost drips with a combination of disdain and fear. It’s something, not being an architect myself and having had a previous career in other sectors, that I’ve struggled with a little. I understand what they mean – in fact it was the ability to make business decisions based on something other than a pure profit basis that attracted me to the organisation in the first place – but it’s also important to recognise that there are aspects of the ‘corporate’ world and its techniques, structures and metrics, that will actually help us do better work, more often.

We’re still seeking the perfect blend of culture and structure, practice and business. But we’re definitely getting closer, and this brand process was both clarifier and catalyst for collective thought and action.

The important thing is that we recognise that there’s a middle road, but that this must be our road and that looking to precedents and ‘best practice’, as seductive as that often is, isn’t our way. We’re doing this predominantly by organic means and progressing more by small steps than big ones. We’re also ensuring these steps are joined up, appreciating complex challenges require thoughtful responses across a spectrum of factors. We’re looking to the future, but taking care to preserve and nurture what’s brought us from 1959 to this point.

With all the talk of disruption in the industry, what are COX’s thoughts on the rise of AI in architecture and design?

Did you know Google has developed AI that generates optimal floorplans for office space? As evocatively dystopian as the mental image is of robots leaning over drawing boards may be, our practice made an early call to embrace new technology without fear. Our point of difference is in accepting new technology without fear as an augmenter of design. We did not accept, however, that it replaces the art-science of architecture. To us these two statements are neither opposing nor competing.

Some traditional functions will become obsolete, yes, but as these recede others will emerge that require a polymath brain and an ethical heart to effectively deploy them. By holding true to the ideal of the architect (or architects) as the informed orchestrator, this technology can always be deployed appropriately and in the context of the whole.

It’s easy to see how in other circumstances that the tail begins to wag the dog, however – the allure of apparently absolute ‘data’ and its surface-objective evaluation of good and bad, right and wrong. It’s a temptation we understand clients especially can find compelling, and as such it should always be presented as a major input into a problem-solving exercise. But neither is it the panacea, more data is usually better but then the filter – the architect’s brain – becomes proportionately more important.

How do you think the architect’s role has changed in recent years and what does the industry need to do to stay relevant in the era of digital disruption?

So much change. The rise and rise of ‘urbanists’ and an array of ever-more niche specialists with ever-more evocative job titles continues. The apparent absolute control of big developers and big construction firms who staff their own in-house designers. Collaborators who’ve now become competitors… but with whom we still collaborate. It often feels like a storm we’ll be swept away in, our identity slowly eroded around the edges, a scenario where traditional roles are reversed and where we become diminished as newer disciplines flourish.

The narrow definition and traditional component parts of ‘design’ in the built environment are unrecognisable from what they were even a decade ago. Architecture runs the risk of being repositioned within this new landscape. On a bad day it could feel like we’re the ‘old uncle’ in the corner at Christmas, loved but increasingly marginalised.

With this increased complexity and the multiplicity of experts, approaches, platforms and stakeholders, our role is even more important. The architect’s training and then subsequent exposure to the sharp end of client expectation and business outcomes results in a professional who is uniquely positioned to thrive in this new paradigm.

To do this effectively requires bravery. Not just acceptance of broad-based collaborators, but an active embracing of new and different inputs to the design process, in full knowledge that we have the sensitivity to draw together these manifold and apparently disparate threads. It really is a case of ‘strong beliefs, lightly held’. We stay true to the immutable ideals of the architect and work in the interests of the communities we serve. We remain flexible enough to understand when to adjust and reinterpret these beliefs in the service of our contemporary context.

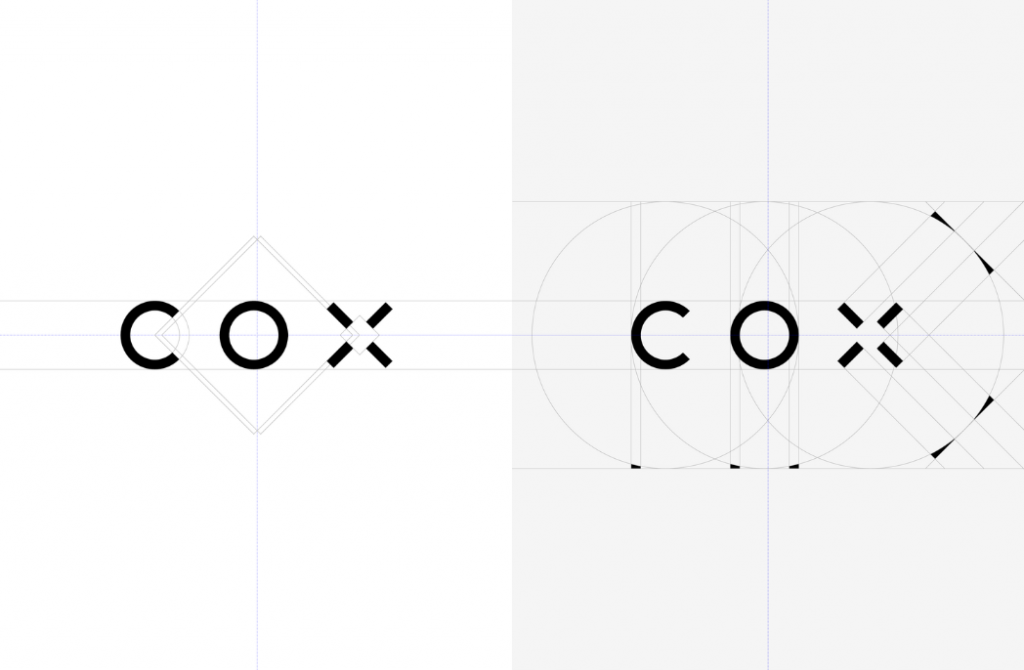

Part of the rebrand included a change in logo. What was the thought process behind that?

COX: Short name, long story.

And this is what the rebrand was both stimulated by and is to reflect.

It’s a lot of meaning for three letters to carry.

Some of the themes are explicit in the branding solution, while some are more subtly implied.

The brand system is deliberately dynamic, incorporating both volumetric and motion graphic elements. It was designed to be bold rather than recessive and built explicitly to allow our stories and our work to ‘sing’; it is there to complement rather than compete.

The work both reflects real change, shines a light on it, but most of all, it gives us a powerful reminder of commitments to ourselves and our communities.