Are bricks made from human urine the future of architecture?

Are bricks made from human urine the future of architecture?

Share

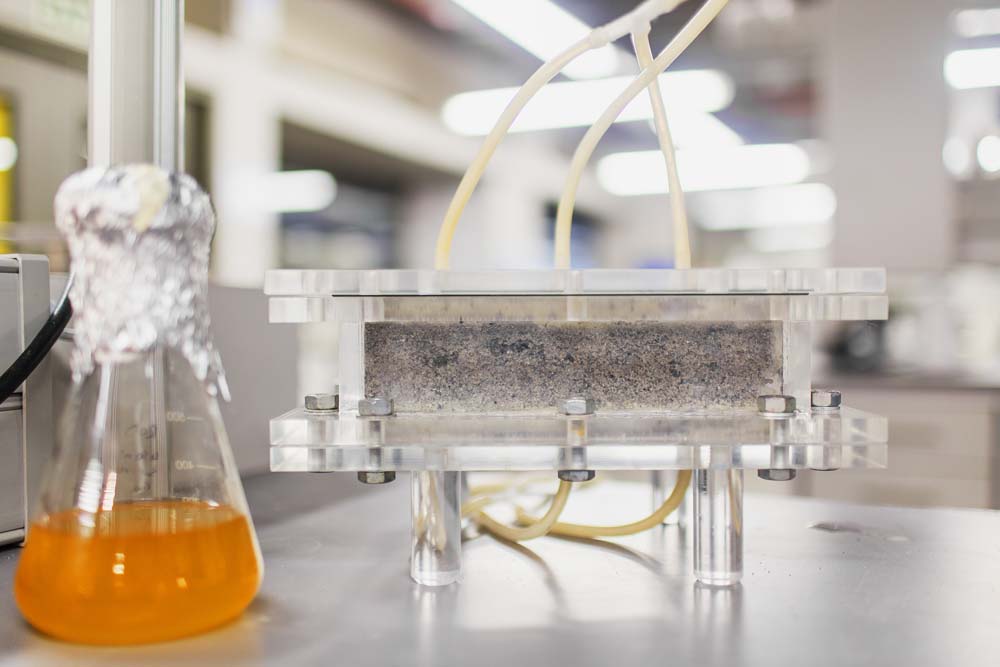

A ‘bio-brick’ made from human urine has been unveiled by University of Cape Town (UCT) researcher Suzanne Lambert as an environmentally friendly alternative to kiln-fired bricks.

The zero waste bricks are made from recovered human waste and can be produced in any shape and strength. Lambert’s supervisor Dr Dyllon Randall, a senior lecturer in water quality engineering, said that the bio-bricks were created through a natural process called microbial carbonate precipitation, that is “not unlike the way seashells are formed”.

The brick is made by mixing sand with bacteria that produces urase – an enzyme that breaks down the urea in urine while producing calcium carbonate [limestone] through a complex chemical reaction. This cements the sand into any shape, whether it’s a solid column, or now, for the first time, a rectangular building brick.

The bricks are made in moulds at room temperature, unlike regular bricks, which are kiln-fired at temperatures around 1400°C and produce vast quantities of carbon dioxide. Lambert believes they could soon be a very real alternative.

“I see so much potential for the process’s application in the real world. I can’t wait for when the world is ready for it.”

The strength of the bio-bricks would depend on client needs, says Randall. “If a client wanted a brick stronger than a 40 percent limestone brick, you would allow the bacteria to make the solid stronger by ‘growing’ it for longer.

“The longer you allow the little bacteria to make the cement, the stronger the product is going to be. We can optimise that process.”

The concept of using urea to grow bricks was tested in the United States some years back using synthetic solutions, but Lambert’s brick uses real human urine for the first time.

Urine is collected in fertiliser-producing urinals and used to make a solid fertiliser, then the remaining liquid is used in the biological process to grow the bio-brick. However, there are a number of hurdles to overcome, says Randall, including collecting urine from those who don’t use urinals and the transport logistics of collecting and treating the waste. Another student is currently working on a solution to this.

Overall, Randall says the work is creating paradigm shifts with respect to how society views waste and the upcycling of that waste.

“In this example you take something that is considered a waste and make multiple products from it. You can use the same process for any waste stream. It’s about rethinking things,” he says.

Photographs courtesy of UCT