Paramount House

Paramount House

Share

Above image: A cantilevered concrete bench shifts from work area to dining as the freefloating portion stretches towards the window. Photography: Mark Dundon and Russell Beard

Location: Sydney, Australia

Design: Citadin, Fox Johnston Architects, Right Angle Studio, Yuki and Fuyuki Sugahara, Mark Dundon and Russell Beard

Text: Elana Castle

Photography: Simon Wood, Fuyuki Sugahara, Douglas Lance Gibson, Mark Dundon and Russell Beard

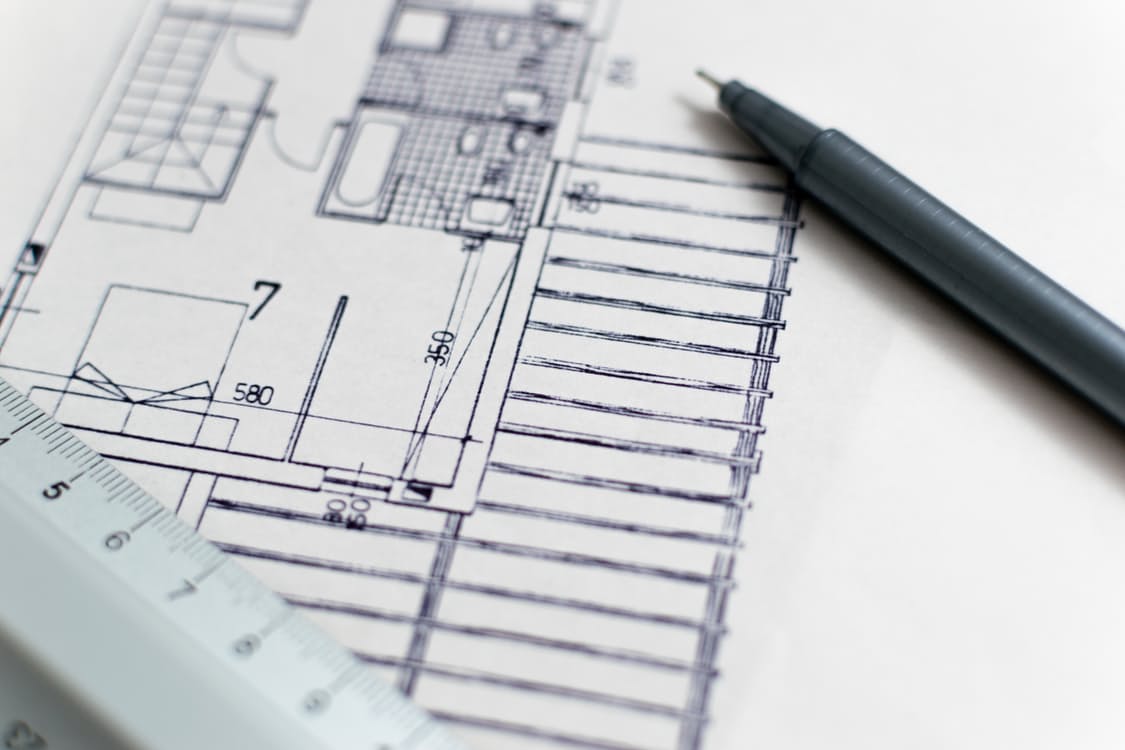

Pursuing best practice in the preservation and restoration of a Heritage site, Paramount House in Sydney proves that history need not be an impediment to creative development. Originally the Australian head office and distribution centre of Paramount Pictures, the 1940s building has emerged anew, referencing both its historical past and a contemporary milieu.

Paramount House is the result of the creative collaboration between a number of key contributors. These include Citadin (the building’s owner), Fox Johnston Architects, Right Angle Studio, Yuki and Fuyuki Sugahara of tokyobike and coffee connoisseurs Mark Dundon and Russell Beard. Tenants include Beard and Dundon’s cafe, Paramount Coffee Project, Japanese bicycle company tokyobike, a dedicated pop-up project space, The Golden Age Cinema and Bar on the lower ground level and office spaces on the top floor.

Paramount House is signatured by the inclusion of history in league with copious amounts of natural light. Photography: Simon Wood

Inspirational to the project’s development were the grand central rail stations in Europe and the buzzy Ace Hotel in Manhattan, where creatives work and mingle. Citadin CEO Jin Ng explains, “We are trying to create a hub not just for the building, but for the wider Surry Hills community.” It was also imperative that the space be readily adaptable for hosting design and lifestyle concepts, such as

The Coffee Collective from Denmark. Almost a decade has passed since architecture firm Fox Johnston began work on the refurbishment of Paramount House. “The program changed numerous times over the years, but the final brief was a blessing, as it allowed us to open up a great Sydney space to the public,” says Conrad Johnston of Fox Johnston Architects. Primary works included the conversion of the redundant main loading dock into an entrance and the extension and improvement of the central, internal courtyard. “Reworking the courtyard was the most difficult aspect of the design, as it involved the removal of a significant amount of the building fabric,” adds Johnston.

Large structural supports are made emphatic by their raw statement of construction. Photography: Mark Dundon and Russell Beard

A palimpsest of history, the ground floor foyer of Paramount House resembles something of an archaeological ruin. Concrete floors, exposed concrete ceilings and unfinished concrete columns in various states of dilapidation provide a layered historical backdrop. Taking advantage of the abundant light, the ground floor explores an appropriately stripped-down aesthetic, making particular reference to both missing and existing Heritage elements through rough, articulated brickwork as well as patterns and plans traced on the floor.

The original film vaults have been converted into service ducts, freeing up the expansive ceiling space. The result is the sensitive rejuvenation of a city treasure and a fertile canvas for the independent interior fitouts. One such incursion is the Paramount Coffee Project, a spacious cafe and concept space, conceived and designed by Mark Dundon of Seven Seeds and Russell Beard of Reuben Hills.

Paramount House is signatured by the inclusion of history in league with copious amounts of natural light. Photography: Simon Wood

The intention was to create a cafe that appeared to have grown out of the space.

To this end, the team, in collaboration with Ficus Constructions, deliberately retained many of the original features, including cut concrete slab ends and rough brickwork, referencing the building’s aesthetic with a limited material palette of pale concrete, black steel, white tiles and timber. Divided into two, the cafe includes a six-seater, poured concrete ‘brew bar’ in addition to a linear serving counter and intimate seating zone. The bar – which features a number of

integrated induction elements – provides customers with an opportunity to interact with the baristas and a variety of brewing techniques. A black steel display cabinet, propped up on a timber shelf on the rear wall, houses a number of limited edition coffee-related products including select roasts and brewing equipment. Suspended, grid-like systems of interlocking, laminated plyboard panels, provide discreet illumination over both spaces.

Bespoke Henry Wilson table and benches provide the central display area within the tokyobike zone. Photography: Fuyuki Sugahara

Similarly, tokyobike has worked within Heritage restrictions to create a unique environment by incorporating a number of loose elements to animate the space. These including four-metre high metal storage units, which sit within the building’s original film vaults, two Japanese squid fishing lamps and a slatted, steel and timber ‘picnic’ table, made in collaboration with Henry Wilson.

“The table and benches are used to display our products, but we plan to use it as a workshop and gallery space in the future,” explains Yuki Sugahara, co-owner of the Japanese bicycle company. “It’s also the largest flexible A-joint table Henry has ever made.” The result is a comfortably sparse space, personifying a pared back Japanese aesthetic. “We wanted an open, simple, warm shop that blended into the existing environment,” says Sugahara.

The simplicity of a pair of Japanese squid lamps add a touch of whimsy. Photography: Fuyuki Sugahara

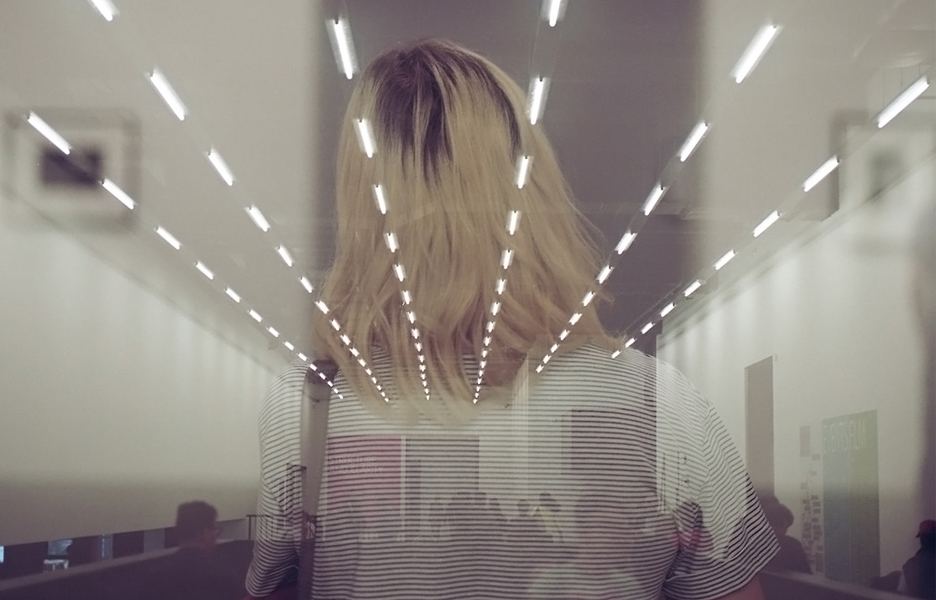

Key to the project is the Right Angle Studios-designed Golden Age Cinema and Bar. “We were influenced by great cinematography and the desire to expose a discovered artefact rather than recreate grandeur,” says Bob Barton, principal of Right Angle Studios, who drew on an extensive team of partners, including brother Barrie, Don Cameron, Matt Fearns, Hugh McCarthy and Phillip Sticklen, to complete the project.

“The screening room is a small, simple space that reflected the pared back elegance of the functionalist building in which it had been hidden for decades,” explains Barton. A narrative of circulation spaces – featuring curved timber and brass walls, a toffee-coloured curtain and a glow-in-the-dark, walnut ticket booth – leads to the bar area.

The ticket booth is a repository of calm elegance reminiscent of the mood of the 1940s cinematic period. Photography: Douglas Lance Gibson

In what was once nothing more than a basement store room, the bar is a richly evocative space, defined by a palette of walnut browns, brass, copper, leather and warm light against deep grey shadows, and a molecular-shaped Lichtstruktur chandelier by Robert Haussmann, which adds to the perfectly created interior drama. In an effort to create an authentic reinterpretation of the original room, Barton and his team went to extraordinary lengths to replace appropriate versions of its primary features, including the original seating.

“Through the talents of our design partner Don Cameron, we eventually tracked down similar chairs in a private cinema being torn down in Switzerland,” says Barton. In combination with the original bevelled stage, the perfect circular curve of the moulded plaster ceiling, a green velvet curtain and suitably cinematic lighting, the space offers a dynamic fusion of old and new. In a nod to the past, the projection room, complete with two original projectors, features leather directors’ chairs, a whiskey cabinet made from an original lens cupboard and a brass coffee table.

A deep olive curtain adds depth and beauty commensurate with the golden years of Paramount House’s previous life. Photography: Douglas Lance Gibson

With the actual screening room in many ways a restoration project, much of the design revolved around the bar space and the labyrinth of corridors through which guests arrive. “Rather than clutter the venue with kitsch historical ornament, we wanted to absorb people into a series of spaces that felt sublimely cinematic, creating an experience that drew from the art of great filmmaking rather than rolling out the prescriptive gauntlet we have come to know as ‘cinema going’,” explains Barton. “We wanted to put people in the script of an evening rather than feel like just spectators at a show.”

Proving to be popular with a significant cross-section of the community, Paramount House is becoming something of a destination, providing visitors with the opportunity to interact with vestiges of the past as well as an ongoing, curated series of lifestyle experiences.