Memorialising the Griffins at Canberra

Memorialising the Griffins at Canberra

Share

Text: Christopher Vernon (The University of Western Australia)

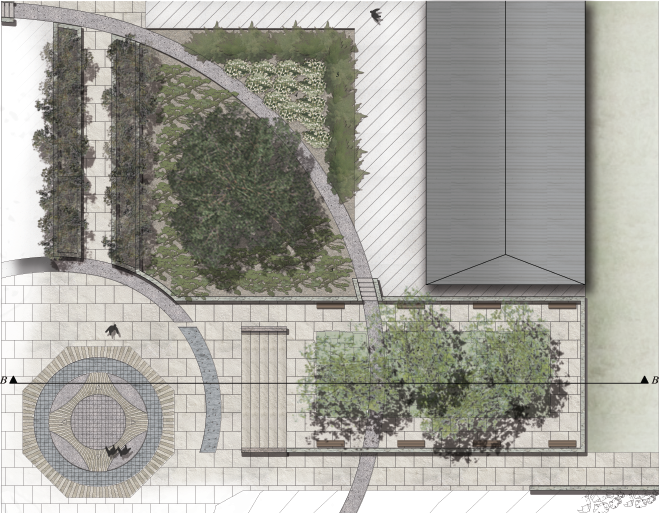

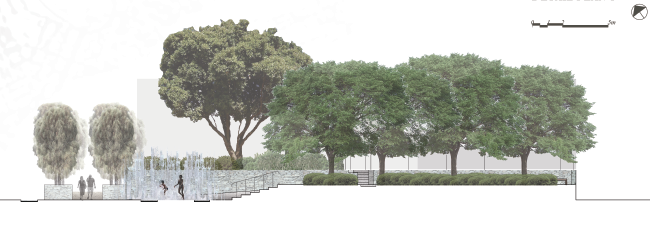

Images: Selected illustrations by Nikolinka Zheleva

A century ago this year, Walter and Marion Griffin voyaged to Australia to begin orchestrating the realisation of their prize-winning design for Canberra. The centenary of the Griffins’ arrival down under makes it timely to (re)consider erecting a memorial to the city’s authors at the national capital, Australia’s greatest achievement in landscape architecture. This proposition is not a new one; it actually has a lengthy history.

The first calls for a memorial to Walter Burley Griffin were made upon learning of his accidental death in India on 11 February 1937 (devastated, Marion would return to Chicago the next year). When the tragic news reached Australia days later, proposals for a monument of some sort to Griffin pervaded his obituaries. On 16 February, for instance, Canberra Times (CT) reported that ‘action will probably be taken to name some prominent part of Canberra after its designer’. Some even proposed that a statue of him be erected at the capital. However, as many believed fledgling Canberra itself to be Griffin’s monument, moves for a statue or memorial nomenclature soon petered out.

Months later, though, he was in fact commemorated with a memorial of sorts, albeit only a two-dimensional one. In May, Alice Henry, a Melbourne journalist and one of the Griffins’ long-standing Australian friends, gifted a photographic studio portrait of Walter to the National Library of Australia (NLA). Touchingly, Walter himself had given the photograph to Henry some two decades earlier. The portrait was now ‘hung in the basement at Parliament House alongside the original plan of Canberra submitted by him at the time of the competition’.

Today the photograph is preserved at the NLA and the plan at the National Archives of Australia – when they were unceremoniously removed from the parliamentary edifice is unclear. When covering Henry’s donation, CT interviewed National Librarian Kenneth Binns, prompting him to offer his own idea for a more lasting and substantial tribute. For him, the ‘most appropriate memorial’ would be ‘a living tree, such as a well-grown oak, transplanted to a central site and encircled by an artistically designed stone seat’. The unidentified journalist endorsed Binns’ suggestion as ‘peculiarly appropriate as symbolising the continual growth of the city’.

The reporter, his imagination captured, next mused: ‘As the oak is the fulfillment of life in the acorn, so Canberra is the unfolding of an idea in the fertile mind of Walter Burley Griffin. Some elevated and central site, such as the hill in front of Parliament House, might form a suitable setting where visitors could sit in the shade of the tree and enjoy a panoramic view of the city. Perhaps no more suitable inscription could be selected for engraving on the stone seat than that inscribed on the tomb of Sir Christopher Wren in St Paul’s Cathedral: “Si monumentum requiris circumspice” (“If you seek a monument, look around”.)’ The poignant sentiment underpinning Binns’ proposal notwithstanding, then, as now, the panorama to be seen from beneath the oak boughs only dimly reflected the city the Griffins envisaged.

In 1957, two decades after Griffin’s death, Canberra’s development was effectively stalled and the notion of a memorial was, understandably, of very low priority, if not altogether forgotten. That year, however, Australia decided, championed by Prime Minister Robert Menzies, to re-ignite Canberra’s development and solicited British town planning authority William Holford for design recommendations. The most dramatic outcome of his consultancy would not be a new government edifice, but the capital’s much-anticipated lacustrine centrepiece.

In 1957, two decades after Griffin’s death, Canberra’s development was effectively stalled and the notion of a memorial was, understandably, of very low priority, if not altogether forgotten. That year, however, Australia decided, championed by Prime Minister Robert Menzies, to re-ignite Canberra’s development and solicited British town planning authority William Holford for design recommendations. The most dramatic outcome of his consultancy would not be a new government edifice, but the capital’s much-anticipated lacustrine centrepiece.

With the lake’s completion in 1964, Canberra was at last unified in a manner compatible with the Griffins’ vision (despite the water body’s divergent outline). Of course, the lake required a name. Menzies reflected in his memoirs: ‘Do you remember that the original designer of this city and the original creator of the whole notion of a lake was Walter Burley Griffin. So far as I know, he has no memorial in this place. He must have one. I want to have the lake called Lake Burley Griffin’. The 1937 call to ‘name some prominent part of Canberra after its designer’ had finally been answered. The memorialising act of naming the water body ‘Lake Burley Griffin’, however, implicitly underscored officialdom’s view that ‘Griffin was [now] history’. Nonetheless, he would not be forgotten and the naming of the lake would not end interest in memorialising Griffin.

Evidently, for some, the ‘Lake Burley Griffin’ moniker was not enough. And, in 1975, the Government returned its attention to the landscape architect, launching a Walter Burley Griffin Memorial design competition that year. This commemorative work, envisaged to be positioned atop Mount Ainslie, was intended to mark the centenary of Griffin’s birth as well as his native USA’s bicentennial the next year. The Government planned to complete construction of the winning design by 24 November 1976, the centenary of Griffin’s birth. Entries were due in October 1975 and adjudication followed that month. Notably, celebrated American town planning authority Edmund N Bacon was amongst the jurors.

Early the next year, Robert T Crane III (of Cope and Lippincott, Architects, Philadelphia; then, coincidentally on secondment from Mitchell/Giurgola, soon to win Australia’s Parliament House design competition) was declared the contest’s winner. In the aftermath of the political upheaval surrounding the dismissal of the Whitlam government, however, the project soon languished.

In April 1976, financial concerns compelled the new government to ‘shelve’ the memorial. Commenting on the decision, Architecture Australia (AA) laconically assessed that Griffin would be remembered only ‘if we can afford it’. Despite this, the project was not, apparently, completely dead. In June 1976, AA noted that documentation of Crane’s prize-winning design was going ahead to ‘bring [it] to a stage where work on building can begin quickly when the Government decides that it can afford to have the memorial’. Whether or not this actually happened is unclear as is precisely when the project was officially deleted.

Around a decade later, another attempt was made to memorialise Griffin. In 1987, Canberran Graham Westlake located Griffin’s otherwise unmarked grave at Lucknow, India. The consequence of his discovery was two-fold. Although the grave had been identified, it also was now, as CT sensationalised on its front page, ‘threatened with desecration because of the shortage of space in the cemetery, unmarked gravesites are being reused’.

In response, calls were actually made to have Griffin’s remains reinterred at Canberra; the Canberra Chapter of the RAIA resolved, for instance, that ‘urgent research should be undertaken to determine how Canberra’s designer, Walter Burley Griffin, and his wife Marion had wished to be interred’ (apparently the group was unaware that Marion had been cremated and her ashes buried at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago). Fortunately, the initiative was apparently never fully pursued. Instead, it more appropriately led to the permanent marking of his Indian grave.

Last year, Canberra’s centenary was celebrated with a plethora of festivities and events, officially spruiked as ‘One Very Big Year’. Of these, the National Library of Australia’s exhibition (guest curated by this writer) The Dream of a Century: The Griffins in Australia’s Capital and the National Archives of Australia’s Design 29: Creating a Capital explicitly featured the city’s designers. Near the year’s end, the ACT Government officially named the vista from Mount Ainslie’s summit ‘Marion Mahony Griffin View’ – poetically counter-balancing the lake’s name.

Apart from these, save for a smattering of other lesser events, the Griffins were ‘hidden in plain sight’ throughout the ‘very big year’ (although it is important to remember that when Canberra’s construction commenced, it was to the Government’s own plan, not that of the Griffins’). Last autumn, this circumstance compelled this writer to re-visit the idea of a Griffin memorial with his third year landscape architecture students.

Conceptually following the 1975 competition brief and utilising the same Mount Ainslie site, the students were charged with designing a memorial to Walter Burley Griffin. In their designs, they were also to accommodate the changes, which have taken place throughout the last thirty-eight years. Most notably, esteem for Marion Griffin as being more than the ‘hand that held the pencil’ fortunately has grown appreciably and the students were now to commemorate the Griffins as a couple. As well, despite a design culture preoccupied with the ephemeral (e.g. the 9/11 Tribute in Light and, more generally, building projections of all sorts) their memorials were required to be lasting, spatial and take the form of a ‘garden’ (as they individually defined it). What is a memorial in the twenty-first century?

To underpin their designs, the students first conducted research focused upon the Griffins’ design philosophy and approach. They next investigated design precedents such as Maya Lin’s iconic Vietnam Veterans Memorial at Washington, DC (1982); Dani Karavan’s Walter Benjamin memorial, Passages at Portbou, Spain (1994) and Louis Kahn’s remarkably timeless Franklin D Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park at New York City (1972 / realised 2012).

A pair of selected outcomes of the design studio (by Nikolinka Zheleva) is illustrated here in the hope that they might inspire, at long last, a built reality – some nearly forty years after the aborted Walter Burley Griffin Memorial design competition.

You Might also Like